Refugee crisis management

Ruth Green

Unprecedented numbers of migrants and an increased risk of terrorism have heightened tensions in Europe. Global Insight examines the issues and legal frameworks surrounding the greatest humanitarian crisis to confront the continent since the Second World War.

Camps, chaos, crisis: three words that go just some of the way to conveying the hysteria surrounding the influx of unprecedented numbers of migrants into Europe. Figures from border management agency Frontex indicate more than 710,000 people were detected at EU external borders in the first nine months of 2015, more than two-and-a-half times the number detected throughout 2014. These numbers start to tell the story of how Europe is being pushed to breaking point.

Of course, the crisis isn’t just about those who have made it to European shores. It also concerns those who have not survived the perilous journey. At least 2,000 people died trying to cross the Mediterranean Sea in 2015, according to the International Organization for Migration. And it was the shocking image of the washed-up body of a three-year-old Syrian boy on the shore in Turkey in September that finally provoked calls for countries across Europe and further afield to share the ‘burden’ posed by the migration crisis.

As countries across Europe struggle to cope with the flow of migrants escaping protracted conflicts in the Middle East, an emergency meeting was held between EU Member States and Balkan leaders at the end of October where they agreed a 17-point plan in a bid to gain control of the situation. Although the Greek islands on the Aegean Sea continue to be most severely affected, Hungary, Croatia, Austria and Turkey are just some of the other countries that are buckling under the pressure.

Emerging consensus

EU leaders agreed to work with UN Refugee Agency, UNHCR, to create 100,000 places in reception centres along the route from Greece towards Germany. Half were to be in Greece, both to slow the steady stream of migrants and prevent people from freezing on their journey during the winter months, and half were to be located in countries to the north.

The discussions promised to increase border surveillance and improve refugee registrations, as well as halting bus and train transfers to the next border that did not have the consent of the bordering country. EU members also agreed to work together with Frontex to detect irregular border crossings and support registration and fingerprinting in Croatia.

Speaking after the meeting, European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker’s unwavering response said it all. ‘We have made it very clear that the policy of simply waving people through must be stopped. The immediate imperative is to provide shelter,’ he said. ‘It cannot be that in the Europe of 2015 people are left to fend for themselves, sleeping in fields.’

ISIS attacks, all change

It seemed as if a consensus had finally been reached, and at last countries were working together. But everything was about to change. Just three weeks later, on 13 November, Paris was rocked by a series of coordinated shootings and suicide bombings that left 130 dead and more than 350 wounded. It took less than 24 hours for ISIS to claim responsibility for the attacks and, within days, rumours were swirling that one of the assailants was a Syrian refugee.

At that point the refugee theory was still purely speculation. This did not stop such rumours fanning the flames of Islamophobia and growing anti-refugee sentiment in Europe. Juncker was quick to make his views known, telling a news conference at the G20 summit in Turkey that Europeans shouldn’t fall into the trap of equating refugees with terrorists. ‘We should not mix the different categories of people coming to Europe,’ he said. ‘The one responsible for the attacks in Paris... he is a criminal and not a refugee and not an asylum seeker.’

Strong words indeed, but if concerns over refugees and the wider security implications of mass migration were high in Europe before the Paris attacks, afterwards they were practically stratospheric as anti-terror raids took place across France and Belgium and both countries pushed through stringent new laws and tightened security measures.

The immediate imperative is to provide shelter. It cannot be that in the Europe of 2015 people are left to fend for themselves, sleeping in fields

Jean-Claude Juncker

President, European Commission

Despite heightened tensions across Europe prompting politicians in some countries to call for temporary border controls, the seeds of many of the security concerns surrounding refugees and migrants in the continent had already been sown. What’s more, the inability of European countries to cope with the sheer numbers of refugee and asylum applications had been apparent long before the fatal Paris attacks.

Gunther Maevers, Co-Chair of the IBA Immigration and Nationality Law Committee and a partner at michels.pmks in Cologne, says the migration crisis had already exposed glaring IT inefficiencies in the Schengen Area – a problem that he says will only worsen as more rigorous security checks are imposed across the continent.

‘Information technology is a big problem,’ he says. ‘The systems in place are simply not made for so many people. In Germany, just to give you an example of how difficult it is, there were so many people coming in that it was nearly impossible to register them all with fingerprints in a proper way. Later on when they go to the local Foreigners’ Registration Office, they have to register them again because there’s no transfer of the data.

‘You can’t guarantee that everyone is registered, and you can’t guarantee that none of them have produced forged documents. This is why in the Paris case it is difficult to know where they came from; it’s assumed they have entered via certain countries, but [in reality] we don’t know.’

Clearly, the panicked and ad hoc approach of many European countries to registering refugees and asylum seekers in recent months has influenced how the crisis has unfolded and worsened. Yet, when you consider that Europe is confronting its biggest humanitarian crisis for over half a century – and worse still, at a time when the continent is still recovering from the fallout of the global financial crisis – the reason why the continent has ended up in this mess becomes a little clearer.

‘Europe is currently faced with an asylum crisis of a magnitude that the continent has not seen since the aftermath of the Second World War,’ Barbara Wegelin, a senior associate at Everaert Advocaten Immigration Lawyers in Amsterdam, who chaired a roundtable on immigration and the refugee crisis at the IBA Annual Conference in Vienna, told Global Insight. ‘It is impossible for only one or several EU Member States to handle this crisis and provide appropriate reception facilities for those people seeking protection, as well as processing their claims. The problem is simply too large and too many-faceted to be dealt with by one or a few Member States.’

Information technology is a big problem. In Germany, there were so many people coming in that it was nearly impossible to register them all with fingerprints in a proper way

Gunther Maevers

Co-Chair, IBA Immigration and Nationality Law Committee

Despite calls from European Commission presidents past and present for Europe to work together to resolve the crisis, too few countries appear to have truly grasped this fact, notes Wegelin. ‘If asylum seekers are equally distributed among EU Member States, on the basis of available space, GDP and the amount already received, not one country will be stretched beyond their limits and the amount of new people that a Member State has to absorb are manageable.

‘At the moment it seems as if only Germany, France and the European Commission are aware that this is the only feasible way forward, given that the civil war in Syria, unrest in Iraq and oppression in Eritrea are not likely to end overnight.’

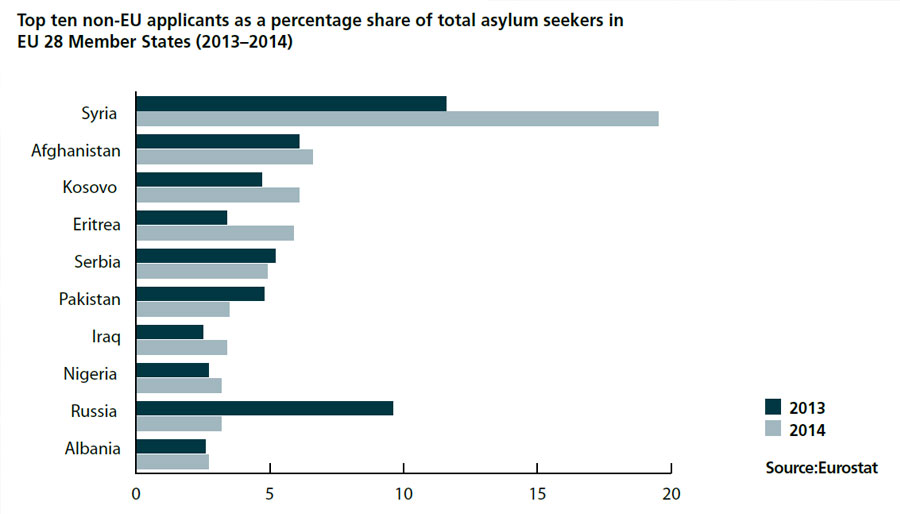

As Wegelin notes, the vast majority of the arrivals are either fleeing warzones or totalitarian regimes. In 2014, 122,115 Syrians, 41,370 Afghans, 36,925 Eritreans and 21,310 Iraqis all applied for asylum status in Europe, according to Eurostat (see chart). And the numbers keep going up: during the third quarter of 2015 an estimated 138,000 Syrians, 44,500 Iraqis and 56,500 Afghans sought protection in EU countries.

But they are not the only ones. Eurostat estimates 37,895 Kosovars, 30,840 Serbians and 16,825 Albanians sought asylum in the EU in 2014, proving that areas in Europe that still harbour the scars of conflict, poverty and limited prospects are contributing significantly to the spiralling numbers of migrants across the continent.

In Germany, between January and August 2015, an estimated 30,000 asylum applications were from migrants from Kosovo. The volume of such applications has compounded the migration problem, creating a type of ‘mixed-migration phenomenon’ that has put increasing strain on border agencies.

However, Maevers says the EU’s new list of ‘safe countries of origin’, which includes Kosovo, Serbia and Albania, has helped ensure their applications are treated differently to applications from Syrian citizens.

‘It all comes down to the question of which citizens have the protected status of being from countries recognised as a safe country of origin, otherwise they will be sent back home straight away,’ he says.

‘Whereas the latter is the case for the Balkan countries, this is not the case for Syria. This is not about first and second-class refugees, but about a classification of the political and humanitarian circumstances in the home country that is seen very differently in the Balkan countries as opposed to Syria, for instance.’

Playing by the rules

Europe comprises 50 countries and the EU 28 Member States, leaving plenty of room for differing views – one reason it’s been hard to reach consensus on how to tackle the crisis. As the situation has escalated, however, this has exposed inherent drawbacks of the Schengen Area’s principle of free movement and the

so-called Dublin Regulation, which determines the responsibility of countries for asylum seekers.

The rules were originally ratified during a meeting of EU leaders in Dublin in 1990, and officially brought into force in 1997. They have been through two sets of revisions since, but the basic premise has stayed the same: people are required to seek asylum in the first EU country in which they set foot, or, perhaps more accurately, the first Member State where their fingerprints are stored or an asylum claim is lodged.

The rules also state that if a person illegally crosses the border into another country, they will be returned to the country in which they originally claimed asylum. Both rules have compounded the crisis, according to Baroness Kennedy, Co-Chair of the IBA’s Human Rights Institute (IBAHRI).

‘I think the Dublin Regulation has contributed to the crisis, because the formulation that requires people to apply for asylum at their first point of entry into Europe is punitive,’ she says. ‘It puts an impossible burden on places like Italy and Greece, which are most easily reached by boat from troubled regions. And Hungary saw itself being placed in the same onerous position.’

Maevers says the authorities in Germany have been visibly unable to cope with the surge in demand for asylum and refugee applications.

‘In Germany I can see the backlog of applications,’ he says. ‘The authorities in charge of asylum seekers have a backlog of no less than 250,000 open cases. That is just too much, it’s impossible to deal with, and I believe the Dublin system was not meant for so many refugees, it would have functioned otherwise, but not in such a scenario.’

Wegelin agrees they are not fit for purpose, but largely because Member States themselves are not playing by the rules. ‘Presently the Dublin Regulation is dysfunctional, for the mere reason that a large number of member states are not applying it consistently – Germany, Italy, Greece and Austria to name a few,’ he says.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel attracted particular criticism in August when she said Germany would process asylum applications from Syrian refugees directly, before later announcing the country was imposing controls along its border with Austria in a bid to regulate refugee numbers.

In early September, Croatia said it would also process Syrian refugees’ asylum applications directly or only allow refugees to pass through its borders to continue on their journey, but later hastily closed seven of its eight border crossings with Serbia after it became overwhelmed by the number of migrants trying to enter the country.

A Syrian refugee child looks on, moments after arriving on a raft with other Syrian refugees on a beach on the Greek island of Lesbos, 4 January 2016. © REUTERS/Giorgos Moutafis

Hans Corell, IBAHRI Co-Chair, says these rapid U-turns in policy highlight the severity of the crisis. ‘It is obvious that introducing border controls within the EU is sending a very serious signal to people in Europe, making people realise that there is really a crisis,’ he says.

‘At the same time, a crisis has to be managed and this may entail extraordinary measures. As a consequence, it is extremely important that there is constructive discussion among the members of the EU on how to share the responsibility for the asylum seekers and refugees that are now turning up at our borders.’

Baroness Kennedy agrees Merkel’s actions signalled a need for the EU to impose consistent policies to prevent Member States acting as they please. ‘Angela Merkel’s instincts were honourable,’ she says. ‘Her retreat from her open border initiative was because the intensity of the flood of people meant that processing became impossible. It is important to have some regulation of those who are entering to manage the crisis better.

‘Has her response added to the crisis?’ Kennedy continues. ‘It certainly made refugees feel more desperate to get through borders before the drawbridges close down. But she also had to manage her own electorate. Populations have mixed responses to the crisis. The human desire to help is diluted with the

self-interested concern about sharing national resources, especially after an economic recession. That is why a fair distribution of responsibility is so important.’

Jelle Kroes, Senior Vice-Chair of the IBA Immigration and Nationality Law Committee and a partner at Kroes Advocaten in Amsterdam, agrees that Germany’s approach has ultimately helped the situation.

‘The discussion has been undertaken in countries like Germany in a very adult way, not pointing to the nitty gritty of the Dublin rules, but just saying that we have a joint obligation to deal with these people,’ he says.

Whether you agree with Merkel’s actions or not, evidently TIME magazine took the view that they were sufficiently significant to bestow upon her the title of ‘Person of the Year 2015’.

Hungary in the spotlight

For all the criticism that has been dished out, no country has been vilified more than Hungary. The country’s resolute measures, pushing through a harsh new

anti-immigration law, erecting a razor-wire fence at its border with Serbia and firing tear gas and water cannons to force migrants back from the border, went down badly with the international community.

Speaking to Global Insight, Zoltán Kovács, a spokesman for the Hungarian government, says the country was simply overwhelmed and looking to the EU for help. ‘Hungary was trying for nine months to do something to stop or at least slow down the influx of people into the EU, trying to keep to these existing rules, and we don’t see the same criticism being directed at others,’ he said in a telephone interview at the end of October.

‘You can imagine that 390,000 illegal migrants going to or going through the country is quite an experience, and an experiment if you like – it’s never been done before. 2014’s numbers were around 44,000 at the end of the year and that was a record high. Nobody has ever seen anything like it, but the most astonishing thing was that it took almost half a year for the EU to acknowledge that Hungary was being affected very heavily.’

Many in international circles remain unimpressed by the country’s approach. ‘It’s amazing in my view that Hungary has taken such a blunt position as they are obviously in breach of the Dublin rules,’ says Kroes. ‘It doesn’t matter where the asylum seeker wants to go, he has to be dealt with in the country where he enters and it’s actually Hungary which is allowing these people to travel through to Germany. Where is the commitment of the other countries?

If asylum seekers are equally distributed among EU Member States, on the basis of available space, GDP and the amount already received, not one country will be stretched beyond their limits

Barbara Wegelin

Everaert Advocaten Immigration Lawyers, Amsterdam

‘Fencing these people off at the border with violence is not allowed. I also think they have installed very drastic measures such as very high penalties or even a prison sentence if you try to open this barbed wire fence,’ he continues. ‘That is not allowed; you are allowed to try and enter a country if you are a refugee, and if you do that illegally it cannot be a criminal act because it’s against refugee law – it’s an integral part of trying to find shelter as a refugee.’

Máté Szabó, Director of Programmes at the Hungarian Civil Liberties Union, confirmed to Global Insightthat, under Hungary’s new anti-immigration legislation, anyone who trespasses the country’s borders now risks imprisonment and even deportation. ‘Those who come through the fence are… arrested and prosecuted for committing a newly codified criminal offence: illegal border crossing,’ he says. ‘The first offender has been sentenced to immediate deportation from the country after an 80-minute trial. Now he is a convicted criminal who cannot apply for asylum, he cannot enter the EU for a year and has to pay a fine of $66. If he tries to enter Hungary again, he will be imprisoned.’

Szabó believes that the new law may even contravene international refugee laws.

‘The Hungarian State is violating Article 31 of the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees by punishing refugees for illegal border crossings before making a decision on their asylum claims,’ he says.

But beyond the negative headlines alleging Hungary’s mistreatment of refugees, Kroes suggests the inadequate registration system is the root of all the country’s problems with refugees.

‘I think the main problem in Hungary is they have not set up a structure where registrations can be made,’ he says. ‘If you don’t register them, you don’t know if these are people that want to go to Hungary, if they want to apply for asylum there or what the chance is of their claim being successful.’

And Kovács notes his country is not alone in this respect: ‘Last week, 25,000 people arrived in Slovenia, but you can’t register 25,000 people in one week or even one month, logistically or technologically, it’s basically impossible,’ he says. ‘In Germany, which is a target country, they are lagging behind at least a year or more with the registration procedures at the migration office – it’s a fundamental problem.’

As of the end of October, Hungary had only managed to register 176,000 of the 390,000 migrants that had entered its borders, according to Kovács, who says the registration rate in the country had dropped considerably since July.

‘After July, when the announcement from Germany came that all Syrian refugees were welcome, there started an ever-growing gap between those who arrived illegally and those who were registered,’ he says. ‘Registration basically stopped when Croatia started to transport people to the borders, because Croatia was claiming to register them and we were trying to keep order.’

Szabó pins the blame on the new border regime Hungary introduced in September, saying it slowed down registrations and channelled migrants into Serbia, where, he says, the registration system is even worse.

‘Those who do not want to commit a crime can come through the entrance points,’ he says. ‘Thousands of asylum seekers have tried to come per day, but less than one hundred asylum requests were registered on 15 September – the first day of this new system. In all of them, the cases were decided in a few minutes, and the verdict was almost always the same: rejecting the asylum claim and expelling the asylum seeker to Serbia. The [Hungarian] government declared that Serbia is a safe third country, but in fact it is not – the country has no asylum system.

‘The decisions also state that the individuals cannot enter the EU – the Schengen Area – for one or, in some cases, two years. The decision informs individuals that they can claim for remedy in the Szeged Court, where they must present in person, but they aren’t allowed to even enter the country… so they have no chance to receive the refugee status – this is a trap for them.’

Despite all the criticism aimed at Hungary, its approach and the perceived chaos that ensued did help force the issue at the multilateral level, causing EU leaders to enter into crisis talks on 22 September and agree a quota plan to distribute 120,000 asylum seekers across 23 European nations to ease the burden on Greece and Italy.

This was despite Hungary, Romania, the Czech Republic and Slovakia voting against the measure and Finland abstaining, marking a rare occasion when EU leaders have pushed through a plan without a unanimous vote.

Hungary has continued to draw international ire. After shutting its border with Serbia with a razor-wire fence in September to stem the flow of migrants, the country was also forced to close off its border with Croatia in mid-October. Both actions provoked outcry across Europe, but Hungary isn’t the only country whose actions have been questioned.

In October, Austria announced plans to erect a similar fence at its main border crossing with Slovenia. Austria and several other countries were also forced to close off their borders on several occasions in the second half of 2015. Although the Schengen Border Code permits Member States to implement temporary border controls in certain circumstances, Wegelin says there are still question marks over the legality of Hungary’s conduct.

‘From a legal perspective this is a complicated issue,’ she says. ‘On the one hand, Hungary is allowed, on the basis of the Schengen Borders Code, to close its borders if there is a serious threat to public policy or internal security for a period of no more than 30 days – although it is possible to prolong this under conditions established by the code – or for the foreseeable duration of the serious threat.

‘On the other hand, Hungary is not allowed, in light of the UN refugee convention, the European Convention on Human Rights and EU asylum directives, to make it impossible for those seeking protection to submit an application for protection. From a legal point of view, it needs to be determined if Hungary has actively discouraged people from applying for a protection status and if those people stopped at the border were thereby exposed to torture or inhuman or degrading treatment.’

While several countries, including Hungary, have been accused of xenophobic behaviour towards migrants, reports in mid-2015 that countries such as Slovakia, Bulgaria and Poland were refusing to accept non-Christian refugees also gave grounds for concern. ‘Discrimination on the basis of religion is prohibited not only under European law, but also under international human rights and refugee law,’ says Corell.

‘Slovakia, Bulgaria and Poland are in clear breach of EU law and the Human Rights Convention if they only take Christians,’ adds Kennedy. ‘It is sad to see nations which have emerged from a recent history of totalitarianism, where rights were sorely abused, failing to see how important it is to protect the vulnerable whoever they may be. The whole purpose of human rights is to recognise our common humanity.’

I think the Dublin Regulation has contributed to the crisis because the formulation that requires people to apply for asylum at their first point of entry into Europe is punitive

Baroness Helena Kennedy

Co-Chair, IBAHRI

Fears that events in Paris would stoke xenophobic and Islamophobic feeling in Europe and further afield were not completely unfounded. In London, police figures revealed attacks against Muslims more than tripled in the immediate aftermath of the attacks. On

19 November, the US House of Representatives passed a major bill to block Syrian and Iraqi refugees from entering the country unless they pass strict background checks.

Denmark has also been criticised for portraying itself as an unwelcome destination for refugees, after slashing social benefits for refugees by up to 50 per cent and passing a law to allow Danish immigration authorities to confiscate jewellery from refugees entering the country.

By contrast, although it’s not all been smooth sailing in Canada, the country’s new Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has stayed true to his word and committed to resettling 25,000 refugees, notes Catherine Sas, an immigration lawyer at Sas & Ing in Vancouver. ‘We’ll see what the aftermath is and some awful things have happened – a mosque was burned down in Toronto and a woman was beaten up in retaliation to the attacks,’ she told Global Insightduring the IBA Biennial Global Immigration Conference held in London in November. ‘But I also saw that they’d put together an online donation campaign to rebuild the mosque, and they’ve already raised more than enough money to try. So it’s emotional, but we’re still taking on the refugees.’

French President François Hollande has also reaffirmed the country’s pledge to take in 30,000 migrants from Syria and Iraq, but said asylum seekers would be vetted to ensure they posed no security threat.

Karl Waheed, Secretary of the IBA Immigration and Nationality Law Committee and founder of Karl Waheed Avocats in Paris, says France’s reinforced anti-terrorism measures follow in the footsteps of the Patriot Act introduced by the US government in the wake of 9/11. ‘The kind of Patriot Act that we’ve passed, an extension of the État d’Urgence (state of emergency) which permits the government to suspend all civil rights, has now been extended by three months until the end of February 2016.’

Although Waheed recognises such measures could raise concerns, he said security is now of paramount importance. ‘The general opinion is – just like the Patriot Act – that we want this, and even defenders of civil liberties agree that we have to give up some civil liberties temporarily for the government to make our world safe.’

There is belief in some quarters that some of the more stringent vetting processes being discussed could pose a danger to refugees. Julia Hall is an expert on counter-terrorism, criminal justice and human rights at Amnesty International and a member of the IBAHRI Task Force on Terrorism. ‘The vetting process is something that states have an obligation to do to make sure that legitimate refugees are getting into their countries and they will all do it, but the way that Syrian refugees are now going to be vetted is extremely rigorous and scrutiny will be even more heightened,’ she says.

‘All you can really do is reduce the risk as much as possible, but to see what’s happening in various European countries and what’s happening in the US, ie, that Syrian refugees cannot come here, and to label an entire group of people in that way is not only incorrect, it’s also really dangerous for them. It puts a spotlight on them as if they are de facto criminals. This is irresponsible, not only for the Syrian refugees who might come, but for the refugees who are in the country already. This political rhetoric is so irresponsible and damaging.’

Indeed, Hall notes that history has taught us that accepting refugees has always involved a certain element of risk, as demonstrated in 1994 when tens of thousands of people fled Rwanda to escape genocide. ‘Rwandan refugees were given a wide margin of appreciation on their asylum or refugee applications, but we know that there were war criminals in those batches,’ she says. ‘Some of them lived quietly for a while; some of them were identified and tried. I realise that’s different from the notion that you would unknowingly let in an ISIS terrorist who would then turn around and commit an attack on your territory, but accepting large populations of refugees has always contained some risk.’

Maria Celebi, a partner at Bener Law Office in Istanbul, remains unconvinced that greater security checks and vetting of refugees will reduce the risks. ‘Turkey already has 2.2 million registered refugees – that’s three per cent of the population – who are not vetted as they’re

visa-free and yet we have no higher incidence of terrorism in Turkey than anywhere else,’ she says, alluding to twin bombings outside Ankara’s central railway station on 16 October that killed 102 people and wounded more than 400 – numbers that are not dissimilar to the Paris attacks.

Although no group has claimed responsibility for the Ankara bombings, the attackers have suspected links to ISIS and affiliated militant groups. ‘So what’s happened in Paris they think will somehow be solved by vetting everybody and all these security checks,’ says Celebi. ‘Yet Turkey, even with an increase of three per cent of the population who are Syrians with no background checks, has had no increase in terrorism.’

Hall is concerned about some of the ‘dragnet’ laws being introduced in France and other European countries. She welcomes, however, the moves by many countries to stick to their refugee commitments despite recent events. It is imperative that refugee policies are backed up by well-thought-out integration policies to ensure refugees’ rights and well-being are protected. ‘It takes a lot more than just saying you’re going to accept a quota, it means you’ve got to create the climate within which those people actually get the protection that they deserve,’ she says. ‘The current climate is not a climate where those refugees will be welcome. They might be able to get in the door, but they arrive in countries where at the highest levels the political rhetoric has not been great, the opposition is horrible in the main and at the street level people are not safe. We’re already seeing signs of Islamophobia and attacks

against people.

‘So [France] can say that they’re going to accept 30,000, but parallel to the security measures that they do need to take to secure the population, there also needs to be hard work and very specific measures that address issues of hate speech, crimes, integration and the general feeling of marginalisation felt by

these communities.’

Moving on from Dublin

Although the US and several European countries have rallied behind France in support of military intervention in Syria, there remains a lack of consensus on refugees, certainly in Europe. The much-lauded EU quota plan brokered in September is facing growing opposition – both Slovakia and Hungary have already filed lawsuits at the European Court of Justice in protest against the mandatory quotas.

Despite these setbacks, Wegelin says the EU quota plan highlights the imminent need to update the Dublin rules to cope with the current pressures placed on Europe. ‘It is not clear to me how the Dublin Regulation, with its mandatory allocation of responsibility subsequent to arrival of an asylum seeker, is compatible with an internal distribution system among the whole of the EU,’ she says. ‘If the EU, in this matter, starts to see itself as an actual union – much like the US – and regards the reception and absorption of asylum seekers as a collective responsibility, then the Dublin Regulation will become void.’

Kovács believes the Dublin system alone is not to blame for the migration crisis, but knows it will take EU leaders time to come up with a viable alternative. ‘You cannot really blame anyone for the badly-shaped European migration and refugee system, because it was designed for something completely different,’ he says. ‘So the blame goes on all Member States, because all 28 were sitting at the table when it was accepted and we are still around the table and it is not working.

‘It is up to the will or ability of countries to fulfil Schengen, but Dublin is different as it has set up a system that was designed for smaller numbers and a different nature to what is happening. Obviously, the European system is in need of a re-design, but by the very nature of Europe, making decisions is a very slow process.’

Although countries such as Jordan and Lebanon have done more than their fair share for Syrian refugees – hosting more than two million of them to date – clearly there are many Middle Eastern nations that can do more.

Baroness Kennedy argues that the responsibility for the migration crisis lies squarely with richer nations. ‘People fleeing war and persecution want to be in places where they have circles of connection – a relative, people from their own village, friends from home. That is what humans do. They come clutching a piece of paper with a name, an address, and our concern should be their safety and wellbeing. The responsibility under international law for refugees should be shared fairly by the

rich world.’

Miguel Moratinos, former EU Special Representative for the Middle East Peace Process and a former Spanish Minister of Foreign Affairs, tells Global Insightthat while Arab States could do more to alleviate the crisis, ultimately their responsibility should be to put an end to the Syrian conflict once and for all. ‘Of course, everybody has a responsibility [to take] refugees, but [the greater] responsibility of the Arab states is to put an end to the Syrian war,’ he says. ‘They will tell you that in Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates, there are already 200,000 Syrians. And they will say that they have given the UN High Commission of Refugees I don’t know how many millions of euros to finance the refugee camp in Turkey. For me, it’s not really a question of whether they’re ready to take some refugees or not, it’s that we have to put an end to the Syrian war.’

Ruth Green is Multimedia Journalist at the IBA and can be contacted at ruth.green@int-bar.org