Chronicle of a disaster foretold

Abby SeiffWednesday 9 June 2021

The Indian government has passed controversial farming laws triggering strikes and protests by more than 250 million workers. These historic levels of unrest have continued even as Covid-19 ravages the country.

In early May, as demonstrations against India’s controversial new farm laws entered their sixth month, a #FarmLawsWorstThanCOVID hashtag went viral on social media. Since late November, tens of thousands of farmers had been gathered at the outskirts of Delhi to call for a repeal of the laws. But with the second wave of Covid-19 ravaging India, particularly the capital, officials renewed their calls for farmers to return home.

The government ‘can do what is in their hands’, the Indian Farmers’ Union (Bharatiya Kisan Union) wrote on social media in response. ‘Citizens are already losing their lives due to Covid-19, on the other hand more than 400 farmers have lost their lives in protest against the three Farm Laws. By repealing the laws – farmers won’t die.’

The three farm laws passed in September 2020 ostensibly aim to reform an agricultural sector long plagued by mismanagement, financial hardship, inadequate infrastructure and outmoded technology. But farmers and their supporters have called the laws, as promulgated, a death sentence. They say these changes will strip hundreds of millions of their livelihood and put them at the mercy of a handful of major agribusinesses – with no chance for legal recourse or protection.

That the protests showed little sign of waning even during India’s devastating Covid-19 outbreak speaks to the weight of these laws. Nationwide, more than 250 million workers have come out on strike against the laws – making it arguably the biggest protest in history.

The fact that farmers and their supporters continue to protest during the pandemic highlights the ways in which these men, women, and children are willing to risk their lives for a chance at survival in an economy that marginalises them

Hardeep Dhillon

PhD candidate, Harvard University

‘If examined from a global perspective what we have witnessed with the farmer’s protests is the birth of one of India’s largest and longest protests, and an international awakening to the conditions of the legal dimensions that impact farming families in India and around the world,’ says Hardeep Dhillon, a PhD candidate at Harvard University who studies the history of South Asia and the US. ‘The fact that farmers and their supporters continue to protest during the pandemic highlights the ways in which these men, women, and children are willing to risk their lives for a chance at survival in an economy that marginalises them.’

Countless legal experts and economists agree, saying the laws do little to address the entrenched issues of India’s agriculture sector.

‘The supporters of the bill advocate the laws are reform measures, and it is important to understand what is meant by reform in this context,’ says Dhillon. ‘Often this term is used to discuss measures that alleviate the marginalization of certain persons and communities. However, in the context of the farm bills, the very communities who the government claims to speak for have been the largest opponents to their passage and implementation.’

‘This raises a very critical question,’ Dhillon says. ‘How can a government advocate for reform measures that aim to better conditions for a community when members of the community are removed from the centre of the conversation and depicted as anti-national, disloyal, criminals, and rioters?’

Law and disorder

Years in the making, the laws broadly amend India’s agricultural sector. The Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act 2020 removes trade barriers within and between states. The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Act 2020 sets mechanisms for farmers’ contracts with companies. And the Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act 2020 deregulates a number of staple foods.

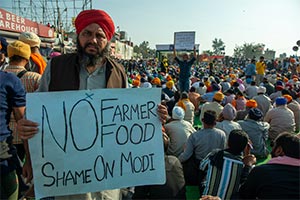

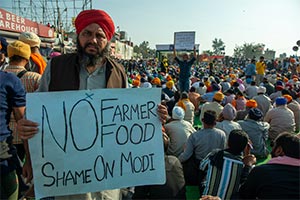

A Sikh farmer holds an anti-government sign at a protest in Haryana, India, 9 December 2020. Shutterstock.com/PradeepGaurs

‘The object of the farm laws is basically to bring in private investment, more technology, to allow the farmer to enter contract farming in a more dynamic manner, and to allow them to get better prices. That’s what the intention of the government is – but the fact that the minimum support price finds no mention in this legislation creates a substantial insecurity,’ explains Nusrat Hassan, Vice-Chair of the IBA Agricultural Law Working Group.

‘If you look at it objectively you’d say great, the farmer is getting the ability to sell to several people, they could sell to a producer, to a supermarket, to a corporation, suddenly they have a much larger market,’ adds Hassan. ‘But what happens is what gets removed is the security they have – they were selling before the mandis, where they got an ensured price for the produce before the sowing of seeds […] It had created a nexus where farmers had a lot of insurance for the price they could get from the market.’

In mid-September, two ruling party ministers introduced the farm bills to the lower house of parliament. By the time the bills arrived, farmers had been protesting them for months. And so in parliament, opposition MPs took up the mantle.

Laws on agriculture fall only under the domain of individual states, opposition parliamentarians noted. Introducing them in parliament undermined the country’s federal structure. Others argued that there was no consultation with stakeholders. And the bills themselves, lawmakers argued, would be devastating to farmers, by removing a critical financial safety net in the form of guaranteed market prices. The Minister of Agriculture brushed off such concerns, and insisted the minimum support price (MSP) would remain. With the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) possessing a majority, the bills swiftly passed.

What gets removed is the security they have – they were selling before the mandis, where they got an ensured price for the produce before the sowing of seeds

Nusrat Hassan

Vice-Chair, IBA Agricultural Law Working Group

Days later, the acts went up for vote in the upper house, where the scene was more chaotic. Opposition leaders called for the bills to be sent to a house committee for scrutiny – a step wholly missing during the bill’s promulgation. The government demurred, pushing the bills forward even after the session had officially expired for the day. Then, ignoring the demands of opposition MPs for a recorded vote, the ruling party chairman insisting on holding a ‘voice vote’ – which tallies verbal ‘ayes’ and ‘nays.’ The ruling party claimed opposition parliamentarians, in their anger, had left their seats, thereby nullifying their votes (a claim readily dispelled by video footage aired by newscaster NDTV).

The manner in which the laws were passed, from the lack of consultation to the manner of vote, drew no small amount of condemnation.

The voice vote ‘is purportedly in contravention of the law-making process stipulated in the Constitution,’ explains Ramesh Vaidyanathan, Vice-Chair of the IBA Asia Pacific Regional Forum. ‘For the sake of convenience there is a presumption that since the Government of the day has a majority, any proposal before the House has the support of the majority, but such presumption is refuted when any member demands voting in the House.’

But, says Vaidyanathan, ‘the most controversial aspect from the constitutional standpoint is whether the Parliament has the necessary legislative competence to pass these laws’.

The most controversial aspect from the constitutional standpoint is whether the Parliament has the necessary legislative competence to pass these laws

Ramesh Vaidyanathan

Vice-Chair, IBA Asia Pacific Regional Forum

In India’s constitution, Schedule 7 clearly delineates what issues fall under legal jurisdiction of the states and agriculture is listed explicitly as a matter for state law, rather than federal. ‘This is not only merely a colourable legislation but lacks legislative competence. Without a constitutional amendment, this could not have been done,’ Bishwajit Bhattacharyya, a senior advocate at the Supreme Court of India, wrote in The Wire earlier this year.

Legal experts argue that parliament has no right to pass laws related to agriculture, and the constitutionality of the laws on these grounds makes up one of the key petitions filed to India’s Supreme Court.

Apart from questions over the way the laws were passed, provisions within the laws have drawn no small amount of criticism. The contract law offers a sweeping legal protection for companies that appears to altogether erase the judiciary, noting: ‘No civil court shall have jurisdiction to entertain any suit or proceedings in respect of any dispute which a Sub-Divisional Authority or the Appellate Authority is empowered by or under this Act to decide and no injunction shall be granted by any court or other authority in respect of any action taken or to be taken in pursuance of any power conferred by or under this Act or any rules made thereunder.’

A tractor driver joins the protest in Ghazipur, India, 23 January 2021. Shutterstock.com/PradeepGaurs

The Bar Council of India was among the many to take aim at that provision. In a December 2020 statement, the Council wrote: ‘The mindset behind the move to oust the jurisdiction of civil courts and transfer of power to bureaucrats, acting as executive officers, to decide disputes between the traders and the farmers, will lead to corruption, and touts will victimize unimaginably. Shutting the doors of civil courts to entertain disputes, pertaining to the subject matter under these Acts will prove disastrous.’

A matter of survival

While the farmers have raised concerns over the constitutional elements, they are most concerned about how market privatisation will affect the MSP and the mandis, which are state-run agriculture markets. These systems are strongest in Punjab and Haryana, the two states at the heart of the protests, but they exist in varying degrees across the nation. BJP officials have insisted the laws don’t touch the MSP, but in opening the markets without guaranteed protections, the mandis and MSP will almost certainly disappear, leaving farmers at the mercy of prices set by large corporations.

‘There has to be some way where the government has to find a way to give them the security of the MSP,’ says Hassan. ‘What they’re asking for is a legislative formalization. They don’t trust the government [promising it won’t abolish the MSP]. Without legislation, it probably will continue for a year or so and then disappear.’

What’s happening now is not an experiment – we know what happens…that’s what people are fighting against – a foretold disaster

Navyug Gill

Assistant Professor of History, William Paterson University

In 2006, Bihar became the first state to abolish the mandi system, allowing corporations to buy directly from farmers. When that happened, ‘farmers were plunged into volatility, more became landless, and there was more outward migration,’ says Navyug Gill, an assistant professor of history at William Paterson University. Some became smugglers, he says, moving their crops out of Bihar and selling them in Punjab, where the state markets ensured far higher prices.

‘What’s happening now is not an experiment – we know what happens,’ says Gill, who studies modern South Asia and global capitalism. ‘That’s what people are fighting against – a foretold disaster.’

The mandi system comes with its own problem. In some areas, the lack of regulation has led to cartelisation, with middlemen taking nearly all the profit from farmers. This has contributed to landlessness and rising debt, along with steep rates of farmer suicide.

MSPs, meanwhile, are offered for crops with little care given to what produce is best grown in a given region, leading to man-made environmental catastrophe. Fifty years of rice cultivation in Haryana, for instance, which requires tube wells to pump water into paddy fields, has seen the groundwater level drop precipitously. The state government is now trying to push farmers away from water intensive crops, though with little success.

L to R: Farmers of Maharashtra state take part in a rally against the central government’s recent agricultural reforms at Azad Maidan. Mumbai, India. 26 January 2020. Shutterstock.com/Manoej Paateel; Indian farmers at the protest at the Singhu border, Delhi, India, January 2021. Shutterstock.com/Im_rohitbhakar; A farmer protests against new legislation passed by the government in Amritsar, Punjab, India, 27 November 2021. Shutterstock.com/SANJEEV SYAL

In light of these issues, in 2004 the government commissioned a large-scale agriculture review. The National Commission on Farmers, more commonly known as the Swaminathan Commission, looked at the key challenges facing farmers and delivered a sweeping plan for reform in a series of reports. ‘They submitted their reports to the government which reviewed it and shelved it, basically ignored it. Many farmer groups are saying we should implement the Swaminathan Commission. One of [the proposals is about] reforming the MSP system. This isn’t a fringe position, it’s a government committee,’ says Gill.

‘The most infuriating aspect is that these laws are referred to as reform’, he adds. ‘Nobody is satisfied with the status quo, everyone on the ground has criticism of the existing system of agriculture. People have been demanding reforms in Punjab for five decades and have been maligned by the government – both Congress and BJP.’

Digging in

In early January, with the protests showing little sign of slowing, the Supreme Court issued an injunction, staying the passage of the laws. ‘We are also of the view that a stay of implementation of all the three farm laws for the present, may assuage the hurt feelings of the farmers and encourage them to come to the negotiating table with confidence and good faith,’ the Court wrote in an order, after unsuccessfully urging the government to take those steps themselves.

The Court also called for a negotiating committee made up of agricultural experts, ‘that may create a congenial atmosphere and improve the trust and confidence of the farmers’.

By the end of the month, however, 11 rounds of talks had gone nowhere and stalled. In late March, the Supreme Court committee issued recommendations in a sealed order that has yet to be made public. The Court said it had consulted with scores of farmer organisations and 18 states to develop a plan to end the deadlock.

The move to oust the jurisdiction of civil courts and transfer of power to bureaucrats […] to decide disputes between the traders and the farmers, will lead to corruption

Bar Council of India

From the start of the protests, meanwhile, the government has been unrelenting in its response. When the first tranche of demonstrators arrived in late November, police blocked the road, firing water cannons and teargas at protesters. That violence has continued intermittently since. As of early March, at least 248 people have died according to organisers and more than 150 have been arrested, though most have been released.

Police have also gone after journalists and activists. In February, police arrested lawyer Nikita Jacob, engineer Shantanu Muluk and climate activist Disha Ravi and charged them with sedition, among other serious offences, after they circulated an online toolkit posted by climate activist Greta Thunberg, which offered ways to help the protests through social media hashtags and petitions.

In addition, the government has rolled out a large scale ‘internet shutdown, slowdown, and mass media campaigns that made it difficult for organizers and protesters to communicate with one another and their supporters across the world,’ says Dhillon, who says this has been among the most effective measures in derailing the protests.

‘For instance, the government shut down the internet in the areas around Delhi and Haryana where the largest number of protesters are concentrated. The Trolley Times, which provides a platform for the farmers’ protest movement, and many labour union activists that remain instrumental in organizing the protests were key in drawing attention to these issues. India surpasses any other democratic country in using internet shutdown and slowdown to undermine protests where the public opposes its policies. In fact, the government used similar measures to undermine the widespread protests that emerged in the wake of the Citizenship Amendment Bill in 2019.’

Those tactics have failed to make a mark, however. More than six months in, the protests show scant signs of waning. Recent surveys conducted by the Lokniti Programme for Comparative Democracy, meanwhile, suggest widespread support for a repeal of the laws in four BJP stronghold states.

In a recent joint letter to the government sent by 12 opposition parties, leaders called not just for an expansion of vaccination production and distribution but for a repeal of the laws as a means to get farmers home to avoid them ‘becoming victims of the pandemic so that they can continue to produce food to feed the Indian people’.

Union leaders and doctors have brought oxygen to the protest sites, and have even set up a vaccination centre offering the Covid-19 vaccine to demonstrators. With the farmers refusing to cave and the Supreme Court showing little inclination to lift its stay on the laws, the government may have few options left at hand. But the ongoing devastation of the pandemic is hitting farmers hard.

‘The issues that farmers had raised in protest about the growing insecurity in their livelihoods have only deepened and worsened since the protests began in fall 2020,’ says Sanjay Ruparelia, the Jarislowsky Democracy Chair at Ryerson University. ‘Farmers were protesting because they felt that the laws as they had been designed left them incredibly vulnerable to big corporations and agribusiness. There were big concerns for indebtedness.’

‘All those circumstances remain the same but they are in a much more acute situation now,’ explains Ruparelia. ‘The Indian economy contracted 8–10% last year in the first wave. The second wave is decimating the economy and particularly it will decimate the rural economy – it’s creeping into the countryside. No one knows the real figure but experts estimate it’s five to ten times higher.

He adds that in rural India, particularly in the northern states, ‘public health infrastructure was extremely weak even before the pandemic. Now, with the pandemic hitting cities, we’re seeing mass migration of seasonal workers back to villages. People are bracing for even worse scenes than what we’ve seen in past weeks. The state of agriculture will take a very big hit.’

Abby Seiff is a freelance journalist and can be contacted at abbyseiff.com