Getting sport back on track

Doping and corruption scandals have ignited the debate over governance of the multi-billion dollar businesses that major sports have become. Global Insight reports on the challenges facing the IAAF, FIFA and WADA amongst other global bodies.

Ruth Green

The world’s major sporting events generate eye-watering sums of money. The London 2012 Olympic Games had an overall budget in excess of £11bn, with in the region of £1.4bn of that coming from international and domestic sponsorship. In 2014, FIFA made $2.4bn from the sale of television rights, $1.6bn in sponsorship deals and $527m in ticket sales for the World Cup in Brazil. The many deals that contribute to these remarkable headline figures go on behind the scenes with the public’s attention far more focused on the track, the pool and the pitch.

"The people in these organisations believe they’re managing something that’s private and outside or above the law and the people themselves also believe they are untouchable

Mark Pieth

Former Chairman, OECD Working Group on Bribery in International Business;

Chairman, FIFA’s Independent Governance Committee 2011–2013

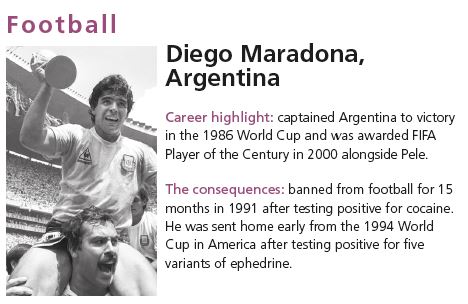

But, when the Swiss authorities raided FIFA’s offices in May 2015 the lid was finally lifted on a 24-year corruption scheme by officials at football’s world governing body. It looked as if the wide-ranging charges, which included racketeering, money laundering and bribery at the very highest levels of international football, couldn’t be topped. Yet the storm was already brewing in another sport that would blow even FIFA’s transgressions out of the water.

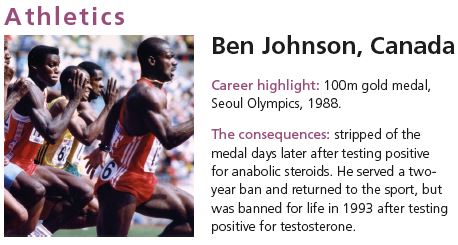

Athletics has, of course, had its share of high-profile drug scandals over the years, but, in December 2014, German broadcaster ARD released a documentary exposing a tangled web of doping and cover-ups at the top echelons of Russian athletics. This sparked a deluge of exposés and further allegations implicating not only Russian athletes, but the country’s athletics governing body, the All-Russia Athletic Federation (ARAF), its anti-doping agency RUSADA and accredited laboratory in Moscow, and even the sport’s international governing body, the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF).

Drugs, money and cybercrime

Within a matter of days the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) set up an independent commission to investigate the allegations, bringing in the agency’s founding president Dick Pound and veteran sports arbitrator and investigator Richard McLaren to oversee the investigation. A month later, Günter Younger, the head of cybercrime at German regional criminal police office Bavarian Landeskriminalamt and former head of Interpol’s drugs division, joined the investigation.

The commission hired private investigation firm 5 Stones Intelligence and seconded several investigative personnel from WADA to look into the allegations. Just as the most intense phase of the investigation was drawing to a close in August 2015, a fresh wave of accusations poured in when a whistleblower at the IAAF leaked 12,000 allegedly incriminating blood tests from 5,000 athletes to ARD and The Sunday Times. WADA announced it was extending the investigation to look into these new allegations.

The commission’s discovery of several documents suggesting ‘activity of a criminal nature’ soon attracted the attention of Interpol, which duly passed the information onto the French authorities. As the French police stormed the IAAF’s offices in Monaco at the beginning of November, the commission was poised to publish its own report. Several senior IAAF officials, including former IAAF president Lamine Diack, were placed under investigation by French police amid allegations of money laundering and corruption.

The stage was set for the release of the commission’s first damning report just days later, which categorically denounced systemic doping in Russian athletics and confirmed the shocking extent of senior IAAF officials’ involvement in the cover-up.

While the doping element marks one major difference between the corruption scandal at the IAAF and that at FIFA, Professor Mark Pieth, who was at the helm of FIFA’s Independent Governance Committee (IGC) from 2011 to 2013, tells Global Insightthat the root of the problem facing each sport is strikingly similar. ‘Factually there’s a fundamental difference because if people get involved in doping they are actually manipulating the game itself, which is comparable to match-fixing,’ he says. ‘The major problem in FIFA is that it’s so badly governed and it’s involved old men stealing money from the sport, but the game itself just goes on. But if you look at it from a more generic perspective, they’re quite similar: the people in these organisations believe they are managing something that is private and outside or above the law, and the people themselves also believe they are untouchable.’

Certainly the contents of the report by WADA’s independent commission were jaw-dropping, but even the report’s authors were taken aback by the reaction it provoked in the media and among the public. ‘The impact of the report was astounding,’ McLaren tells Global Insight. ‘I really didn’t expect it.’ And McLaren has been involved in his fair share of investigations, not least the $24m two-year major league baseball inquiry linked to the infamous doping scandal that engulfed the San Francisco Bay Area Laboratory Co-operative (BALCO) and its owner Victor Conte in the early 2000s, which implicated dozens of athletes for taking performance-enhancing substances.

‘The next day the commission’s work and pictures of us were on the front pages of 191 countries,’ he says. ‘Within five days of the report going public every single recommendation had been accepted and either adopted or steps had been taken to implement what was said. Neither Dick Pound, Günter Younger nor I have been involved in anything where the recommendations made have been accepted and acted on with such speed.’

WADA swiftly suspended the accreditation of the suspect Moscow laboratory and declared RUSADA non-compliant. On 13 November, the IAAF provisionally suspended ARAF from all international competitions. If the athletics body fails to comply with strict criteria set out by the IAAF and regain membership, there’s the very real risk that no Russian athletes will reach the starting blocks at this year’s Summer Olympics in Rio.

Although WADA has already made moves in recent years to strengthen its own independent compliance and regulatory function, McLaren says the agency’s reaction to the report has been extremely encouraging. ‘The report was a watershed for WADA as it recognised it did have to take up a regulatory compliance role, which it has always had, but it’s never fully been part of its thinking and operations,’ he says. ‘The report turned a light on that this needed to be done, and they’re now taking those steps.’

Olivier Niggli, chief operating officer and general counsel at WADA, tells Global Insight that the report will be a real game-changer for the sport. ‘The contents are, as we know, very troubling, however they now offer a real opportunity for the relevant organisations to “seize the day”, act on the recommendations and make big strides where there were deficiencies,’ he says. ‘This is vital for the clean athletes, and to reinforce public confidence in sport.’

Niggli also says it reinforces the need for a dramatic overhaul of governance in international athletics and other sports worldwide. ‘What’s clear following the conclusion of the Independent Commission is that we all – those of us in anti-doping, athletes and the public at large – expect the organisations that serve sport to be much stronger in areas of governance,’ he says. ‘We operate under tight resources in anti-doping, and we have to be strategic and work together as a unit if we are to level the playing field.’

A question of governance: from Festina to WADA and beyond

Of course, calls for better governance in sport are important, but the real question remains: if we can’t trust international federations to self-regulate, then who exactly is best placed to oversee sport?

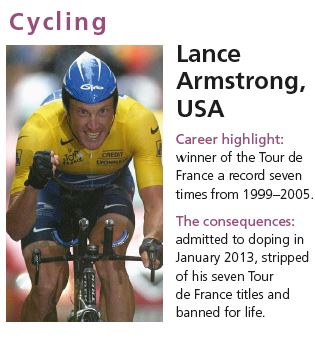

WADA, as the body that has already conducted the investigation into the IAAF, would be an obvious candidate. Since January 2015, thanks to an update to the World Anti-Doping Code, the agency now has the power to carry out investigations of this kind – something it wasn’t previously at liberty to do. It’s worth remembering, of course, that WADA itself was created in 1999 as an independent body in direct response to the Festina doping scandal that marred the Tour de France in 1998 when customs officers at the Belgian-French border discovered several hundred grams of anabolic steroids, Erythropoietin (EPO), syringes and other doping products.

Richard Young, managing partner of Bryan Cave’s office in Colorado Springs, lead draftsman of the Code and lead prosecutor in numerous high-profile doping cases, says there is an argument for WADA to step in and take over the drug-testing function at international sporting federations. ‘There would be logistical issues, but international federations have a number of missions, one of which is clean sport, and a number of their other missions conflict with clean sport,’ he says. ‘Whereas WADA only has one mission – clean sport – and it has the expertise.’

The role of National Anti-Doping Agencies (NADOs) is also significant here, says Young, since they lack some of the competing interests that typically affect international federations. It was for this reason, he says, that the Australian Anti-Doping Agency (ASADA) was able to take such a hard line in the recent Essendon scandal, which saw 34 current and former players of the Australian Rules football club banned from the sport in January over doping offences. ‘If you look at what happened to ASADA in bringing the Essendon case initially, people in the agency came under enormous pressure from both sport and politicians to not do what they did,’ Young says, who was lead prosecutor on the case. ‘It was not a slam dunk case; it brought down a tonne of flak from politicians; the Australian Football League was not happy with how it affected their sport and it cost people their jobs – it has had a significant impact on the sport.

The report was a watershed for WADA as it recognised it did have to take up a regulatory compliance role

Richard McLaren

Co-author, WADA independent commission report

on doping and cover-ups in Russian athletics

‘If you put an international federation in that same rock-and-a-hard-place situation, you have a very different perspective on it than a body like ASADA,’ he continues. ‘They would question what this is going to do to their budget, their reputation, their ability to host a world championship or be the next bidder for the world championship and so on. There are a lot of competing considerations that will go into making that very hard decision that a person whose only job is anti-doping simply doesn’t have.’

Although, as the Russian scandal demonstrates, even if NADOs lack some of the potential conflicts of interest typically associated with international federations, they are not immune to corruption.

Alberto Yelmo Bravo, an external legal consultant at Spain’s National Anti-Doping Organisation (AEPSAD), agrees that the scandal shows how corruption can undermine even the most effective and robust of anti-doping systems. ‘Regulatory systems are important and in terms of doping, the people at WADA carry out important work overseeing everything that a national anti-doping organisation does both at a national and international level,’ he says. ‘This is important, but you also have situations like in Russia where the people that were involved in the overseeing have also been part of the corrupt system.’

For this reason, argues Yelmo Bravo, the Russian situation is distinct from previous doping scandals, even Operación Puerto – the infamous investigation by Spanish police into an international blood doping ring set up by Spanish doctor Eufemiano Fuentes, which implicated various well-known Tour de France cyclists in 2006. ‘When we talk about other countries that have problems with doping, it’s not as extensive – it’s not state-sponsored doping,’ he says. ‘This is a lot more concerning because it involves extorting athletes in your own country and forcing them to make a decision: to get involved in doping or not to compete in national selection at the international level.

‘The other side of it is that you as an athlete know that as soon as you get caught you have to be able to pay a large amount of money – as appears to be the case in this instance – in order to effectively ‘buy’ the silence of your anti-doping organisation and your national sporting organisation.’

The IAAF, integrity and conflicts at the NADOs

Jonathan Taylor, a sports law partner at Bird & Bird and external counsel for the IAAF on anti-doping and related issues, believes the Russian situation highlights the extent to which NADOs can find themselves conflicted. ‘An international federation’s job should be to say they want to uncover cheats,’ he says. ‘And there will be a perception now, questioning whether they’re covering up, but equally you could question whether a NADO would cover up a case involving a national athlete because its national pride is at stake.’

Taylor says it’s tempting to conclude this issue will be resolved simply be removing the IAAF from the equation and appointing an independent supra-national body to regulate the sport. However, he feels this would be a flawed approach. ‘Some people are saying that the IAAF and other international sporting federations shouldn’t be involved in integrity issues. I think this is ridiculous as I think they’re the best placed to be involved and second of all you don’t want to give them the excuse to say doping isn’t their problem.’

The Russian scandal clearly has raised many questions about the IAAF’s capacity to crack down on doping. However, Adam Brickell, director of integrity, legal and risk at the British Horseracing Authority (BHA), says it’s necessary to differentiate the federation’s track record on anti-doping from the corruption that has facilitated the scandals in Russia and other countries. ‘Many people might look at this as an anti-doping issue, but I don’t think it’s quite as straightforward as that,’ he says. ‘Certain individuals have managed to use the anti-doping programme for their own corrupt activities, but the IAAF anti-doping programme itself has always been groundbreaking and has led the way. It’s just unfortunate that people will take the view that athletics has been getting that wrong as well, but it’s the institutional and governance issues that have created the opportunity for corruption to take place.’

Brickell, who has been at the centre of BHA’s own efforts to clean up British horseracing, believes sports can and should regulate themselves as long as there are sufficient safeguards put in place. ‘I feel that often the best people to regulate the sport are people within the sport itself, but there need to be sufficient checks and balances and structures in place to allow for proper demarcation between commercial interests and regulatory aspects, and to make sure there are robust governance structures in place to avoid conflicts arising. I think you can have that while still having a sport regulating itself.’

One issue, however, with self-regulation, particularly after a scandal of this magnitude, is that public trust is very difficult to win back. ‘There are a lot of challenges in cleaning up sport and keeping it clean,’ says Young. ‘One is that you have had and still have, to some extent, the concept of the fox guarding the henhouse,’ he says. ‘Take the experience we’ve had in the US where the US Olympics Committee (USOC) did testing and each one of the national governing bodies prosecuted the cases. I think the USOC did a good job and I think on the whole the national governing bodies tried to do a good job but despite this, nobody trusted the results internationally and it was just viewed as the fox guarding the henhouse.’

It was for this reason, says Young, that the US Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) was established in October 1999. ‘It’s the worst of both worlds – you’re spending a lot of money, you’re busting your best athletes and nobody gives you any credit for it because they assume you’re a fox. That’s why the US took it all away from the national bodies and the USOC and gave it to USADA as an agency that is completely independent of sport, to which athletes are subject to testing and adjudication.’

Although doping appears to be just one of the IAAF’s myriad problems, in many respects the federation is now facing exactly the same conundrum. In February 2014 – nine months before the shocking ARD documentary – it established an Ethics Board as its own independent judicial body specifically in response to growing concerns that some of its members were violating its code of ethics.

The calibre of the now nine-strong Board is undeniable. Chaired by prominent English barrister Michael Beloff QC – who, along with his other impressive CV entries, acted as Sebastian Coe’s ethics tsar for the 2012 Olympics – the other eight members are a dream team from the legal, sport and academic worlds and include former IBA president Akira Kawamura and Justice Catherine O’Regan, a current member of the IBAHRI Council. However, there continues to be scepticism surrounding the Board’s capacity to bring about long-lasting change at the IAAF.

The limitations placed on the Board’s remit and powers from the outset have only contributed to this perception. Initially it was only able to carry out investigations into complaints if they were made by someone within the federation – something which Beloff himself has described as ‘anomalous’.

Are doping rules up to scratch?

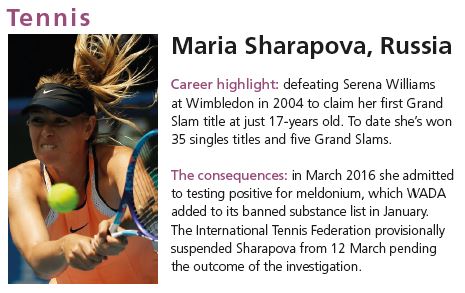

Apart from the shock factor created by Russia’s doping debacle, the scandal has also raised questions of whether the doping rules governing sports worldwide are still fit for purpose.

The World Anti-Doping Code came into force on 1 January 2004 in a bid to clean up the world’s sports and harmonise anti-doping practices across all sports and countries. It has been revised three times and has been adopted by more than 600 sports organisations, including international sports federations, national anti-doping organisations (NADOs), the International Olympic Committee, and the International Paralympic Committee.

Richard Young, lead draftsman of the Code, believes the legislation has made a huge difference in cleaning up sport: ‘Before the Code everyone had different anti-doping rules,’ he says.

‘You would get a lifetime ban in rowing for something that you would get a three-month ban for in cycling. The rules were full of loopholes. There was no uniform agency to appeal or place to appeal to – now we have uniform rules, we have a uniform list, an agency – WADA – and a tribunal – the Court of Arbitration for Sport – for when either a national anti-doping agency or an international federation gets it wrong. We didn’t have any of that before.’

The most recent revisions to the code in January 2015 have made doping regulations stronger than ever, according to Alberto Yelmo Bravo, an external legal consultant at Spain’s National Anti-Doping Organisation (AEPSAD). ‘The new code established new guidelines in terms of education and investigation, leading to a much more complete and robust programme,’ he says. ‘For this reason I would say that 2015 was a historic year for the fight against doping. The most important legal development was that sanctions for doping increased from two to four years, but also a new concept was introduced – intention. Previously in the 2003 and 2009 codes there were some reductions based on lack of culpability, but the concept of intention wasn’t so clear.

‘Of course we have the problem that many people knowingly cheat to improve their physical performance but there are also those who unknowingly take banned substances. For example, they may be given some medication that is prohibited or use a supplement that is contaminated, but the sportsperson isn’t aware. The new code makes this distinction.’

Jonathan Taylor, a sports law partner at Bird & Bird who has been keenly involved in revising the code’s standards for testing, believes the present doping regulatory structure is sound, but says the question remains whether people are going to use the tools made available to them. ‘I think the infrastructure is there, but it’s up to the anti-doping organisations whether they want to use the tools that they’re given,’ he says. ‘For example, the Athlete Biological Passport (ABP) is a very powerful tool that catches blood doping, but not everybody is using it because it’s expensive, it’s difficult and guess what, it uncovers cheating.’

As Young attests, you can have all the rules in the world in place, but there will always be the issue that certain countries, perhaps where the rule of law is lacking or cultural issues get in the way, are not coming from the same starting point: ‘Pretty soon you have a set of rules and a system that are like a high-end Ferrari race car. But the problem is a lot of the sports in a lot of the countries are just learning to drive. It’s been a challenge to make the code universal because we needed it to be a one size fits all, but we have to be realistic that people are coming at it from very different levels of expertise.’

Former IBA president Akira Kawamura agrees the bigger problem is application rather than the robustness of the rules themselves: ‘WADA and the code function very effectively as the global ethical standard of doping and they have a strength which no one can question,’ he says. ‘However, we must admit that they may not be implemented with the same degree of care in every country throughout the world.’

|

In the beginning, it was not able to suspend anyone while investigations were ongoing, or even disclose that they were being investigated, all of which only added to the view externally that the IAAF was doing nothing.

In fact, in August 2015 as Pound, McLaren and Younger were drawing their own investigation for WADA to a close, the Board’s independent investigator Anthony Hooper, a former Lord Justice of Appeal of England and Wales, recommended disciplinary charges should be brought against the former president’s son Papa Diack and three other sports officials accused of concealing doping violations by Russian athlete Liliya Shobukhova. This only came to light three months later when the IAAF Council finally loosened the rules on 6 November and allowed the board to disclose information about its ongoing investigations.

A hearing was held in December and on 7 January 2016 the Board announced it was imposing a lifetime ban on three of the officials, including Diack, who had previously served as a marketing consultant for the athletics body. It also issued Gabriel Dollé, former director of the IAAF’s medical and anti-doping department, with a five-year ban.

By this time the Board had also announced the provisional suspension of three Kenyan athletics officials from taking part in athletics-related activity over allegations of corruption and the ‘potential subversion of the anti-doping control process’.

These were the strongest signals yet that the IAAF was finally taking some action, but they paled in comparison to the damning findings of the second WADA report, which was published just over a week later on 16 January. To the outside world at least it still appeared as if the IAAF was on the back foot.

Clearly the initial lack of openness over what the IAAF’s Ethics Board was doing only contributed to this perception. Kendrah Potts, legal director at Mishcon de Reya, stresses how vital transparency is in regaining public confidence in a sport. ‘Regaining public trust is not about what’s happening behind the scenes, it’s about how you portray what you’re doing and cycling didn’t get that right,’ says Potts, who knows this all too well, having acted as legal counsel to the commission established by the Union Cycliste Internationale to investigate doping and related allegations of corruption and mismanagement in cycling.

Too many mistakes

‘You can’t paper over the cracks. It’s not enough to go out there and say you’re trying to make it better and say: “Look we’ve created a new ethics board or integrity unit”. You’ve got to have systems in place that mean that the integrity of the sport as a whole isn’t undermined, otherwise people will never believe that you’re trying to do a good job and have a robust system.

‘The really sad thing is that athletics is throwing that opportunity away with the reactions they’re producing in the press. Everyone makes mistakes but they’re making too many. It’s got to be a change of attitude.’

If the IAAF is looking for inspiration on how to reform amid intense media scrutiny, it would do well to look to the BHA, which went to great lengths to tighten its rules and restore its image in the wake of two major scandals in 2013. The Mahmood al-Zarooni scandal resulted in the trainer admitting to administering anabolic steroids to 15 horses and being disqualified from the sport for eight years. The Sungate scandal emerged when trainers at Newmarket were found to be giving horses a drug of that name containing banned anabolic steroid. ‘They are not the sort of the headlines you necessarily want,’ admits Brickell, ‘but cases like that firstly show the system is working and provide an effective deterrent for others. Secondly they provide an opportunity to make a case for more resources to take our system forward, and to set the agenda at an international level to try and get other jurisdictions to come along with us.’

We all – those of us in anti-doping, athletes and the public at large – expect the organisations that serve sport to be much stronger in areas of governance

Olivier Niggli

General counsel, WADA

The BHA had already demonstrated its ability to investigate corruption, having carried out a widespread security review in 2002 and established an internal Integrity Unit. Another review was carried out in 2008, but it was the 2013 scandals that prompted the most dramatic change – in March 2015 BHA introduced a zero-tolerance policy to steroids and increased the ban on horses breaking the rules from six to 14 months.

It recently undertook a third integrity review, which Brickell hopes will build on the ‘track record and the evolution of our integrity unit, which is probably the first of its kind in sport and of which we are rightly proud.’

However, FIFA makes clear, for some organisations, change does not come easily. Pieth, who was tasked with supervising the football body’s reform, said the first step was to introduce independent and transparent structures that were severely lacking in such an institutionally nepotistic organisation.

‘In my experience it was crucial that the IGC put in place independent bodies within the organisation that were there to stay, starting with the Ethics Committee and we also introduced an Audit and Compliance Committee headed by Domenico Scala that was totally independent,’ says Pieth.

Not all changes were as straightforward though, notes James Klotz, a partner at Miller Thomson in Toronto, who worked alongside Pieth as a member of the IGC. ‘There was opposition to some of the reforms that the IGC proposed,’ says Klotz, who also serves on the IBA’s Management Board. ‘The reform I felt most strongly about was that of putting independent directors on the executive committee at FIFA, in order to create greater transparency. At FIFA, that reform was not accepted. Why? The institution did not see the need… for all the reasons you can imagine. I still think the reform is a good one.’

In many ways the FIFA experience has done little to quell concerns that internal governance and ethics committees lack long-term effectiveness. In October 2013 Pieth stepped down from the commission as the decision by longstanding president Sepp Blatter to run again ‘was against everything we had been doing’, he tells Global Insight.

A rift between the chair of the adjudicatory chamber of FIFA’s Ethics Committee, Joachim Eckert, and independent investigator Michael Garcia saw the latter abruptly resign in December 2014 after he alleged an ‘erroneous’ version of his investigation into the World Cup bidding process was published.

Although the FIFA example is extreme, it illustrates the extent to which internally appointed commissions risk having their hands tied, says Mishcon’s Potts. ‘Those are the sorts of issues you face when you have an internal disciplinary body or investigative chamber,’ she says. ‘Michael Garcia was sent off to do his report, did his report and then it was censored. If you are reporting to a governing body, they have all the control, but if it’s an independent one like the one at WADA, then, as we’ve seen with the IAAF investigation, they have been able to be bold and they have produced a pretty much uncensored report.’

Despite these setbacks, the Ethics Committee did eventually succeed in debarring 40 members of FIFA’s Executive Committee, including Blatter and vice-president Michel Platini. These moves, and the recent election of Swiss lawyer Gianni Infantino as FIFA’s new president, suggest – on the face of it at least – that change may finally be on the cards. However, Klotz, stresses that true change will only come if Infantino leads by example. ‘For real change to occur at FIFA, the culture must change,’ he says. ‘That change begins with the proverbial proper ’tone at the top’. Following his election, Mr Infantino has said that FIFA needs to implement the reform and implement good governance and transparency. He has that part right.

‘However, the tone at the top must now firmly align with the actions that the organisation takes. At the same time that FIFA elected Mr Infantino, it also adopted some additional reforms. However, FIFA’s reform is a process, and there are still improvements to be made. Time will tell, and at this point, we can only speculate as to whether his election is merely another chapter in the FIFA book, or the first chapter in a new FIFA era.’

Even with the IAAF Ethics Board’s expanded powers, Beloff realises there is still a problem in terms of public perception about the board’s role and how it operates. ‘Essentially it comes down to the fact that we cannot act other than fairly and that does involve taking time, which may not synchronise with the media’s understandable desire for swift headlines or soundbites.’ he says. ‘At the end of the day, as an adjudicatory and disciplinary body, we can only act on evidence. We have a first-rate, highly experienced team with a wealth of legal, ethical and sporting experience and our decisions are reached by serious people after a serious process. We would therefore hope that those decisions are respected even when they contradict certain people’s expectations as to the result.’

As allegations of widespread doping in Kenya, China and other countries continue to surface, Beloff stresses that the board does not have the same responsibility as either WADA or the NADOs. ‘The only ethical matter that isn’t in our remit – but quite properly so – are pure alleged doping violations in athletics, which are to be dealt with by another IAAF body. We might, however, be involved if adverse drug test results were deliberately not being brought to light or covered up. The boundary is not always easy to define because actually failure to report such a result is in itself a violation of the anti-doping provisions, but where there’s an allegation of organised or orchestrated suppression of results that’s when we would certainly be engaged.’

Bidding under scrutiny

As with FIFA, the IAAF’s bidding process for cities to host their major competitions is coming increasingly under scrutiny. In April 2015 it was announced that the 2021 World Championships would be hosted by the US city of Eugene, where sports clothing brand Nike started out and today the company’s headquarters is situated just 100 miles away in Portland. However, it later materialised that the normal voting procedure for hosting cities did not take place and, by early December, French prosecutors were said to be investigating the decision.

IAAF President Sebastian Coe himself has come under fire over Eugene’s winning bid, given his longstanding links with Nike. He previously held a handsomely remunerated ambassadorial role for the brand before choosing to sever his commercial relationship with the company at the end of last year, after consulting the Ethics Board.

The IAAF Council has already referred two bids to the Ethics Board – the 2017 World Championships, which are to be hosted by London, and the 2019 World Championships, which are due to take place in Qatar. Beloff declined to confirm if the Board would also be investigating the Eugene bid. ‘It has been alleged that the decision on Eugene may have bypassed the rules that were in place at the time,’ he says. ‘I would only say, without purporting to comment at all on the Eugene case, that in principle a decision can be unusual without being unethical, and the Board is only concerned with ethical issues and has no power to investigate anything short of that.’

Whether the suspicions around Eugene are well-founded or not, it does raise questions once again about how these bidding processes are governed and how vulnerable they are to bribery, whether from sponsors or even governments.

We cannot act other than fairly and that does involve taking time, which may not synchronise with the media’s understandable desire for swift headlines

Michael Beloff QC

Chair, IAAF Ethics Board

As one lawyer told Global Insight, there are two parts of the world that are playing a significant role in bankrolling international sport. ‘If I’m an international federation and I want to get top dollar for my world championships, there are only two places I’ll go – Russia and the Gulf States,’ he says. ‘If you figure out what Russia paid to get the World Swimming Championships in Kazan and what Manchester paid to get the World Swimming Championships in Manchester and the only countries in the world that would have paid more or would have been remotely in Russia’s league are the Gulf States.’

The sheer money involved in Russia hosting the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi certainly raised many eyebrows. Originally budgeted at $12bn, soon the figure ballooned to over $51bn, surpassing the estimated $44bn cost of the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing as the most expensive Olympic Games in history.

Of course, as Beloff and others note, although the Board can undertake extensive investigations, it still lacks the powers bestowed upon law enforcement and other government agencies. ‘It is very important for people to recognise that ethics committees of sporting organisations are not the same as governmental authorities – for example the Ethics Board can’t subpoena bank accounts or compel potential witnesses to attend disciplinary hearings,’ he says. ‘The powers of such derive from contract, not the public law of the land. This does inevitably place some limits on their capacity to fulfil their role. They must at root rely on collaboration and cooperation, not coercion.’

Intelligence gathering from police and customs is a vital part of the investigation process, says Jonathan Taylor. ‘To catch cheats you want to use intelligence and intelligent means, so that means not just drug testing but gathering information from other places,’ he says. ’That’s where the NADOs come into their own because if it’s a public body it can get that information. Police won’t give that information to a private body, but they’ll give it to a public body and that’s why UK Anti-Doping was set up as a public body and it’s worked very well.

‘They’ve given lots of long bans to people who are trafficking and supplying drugs to athletes and actually that’s what you want, you don’t necessarily just want the athlete, you want the coach, the doctor, the trainer – the whole entourage.’

Speaking to Global Insight after news broke at the beginning of April that a UK doctor was alleged to have provided performance-enhancing drugs to numerous British athletes, Taylor says: ‘There might still be tricky legal issues, for example whether the sport has sufficient jurisdiction over a doctor, or if not then whether the doctor is in breach of General Medical Council rules. But without having the evidence in the first place, for example from law enforcement, you don’t even get the chance to consider those issues.’

Brickell’s team at the BHA, which includes analysts equipped with the skills to pull together and present information such as telephone records, betting records, IP addresses and cookie data, is better-placed than most sports organisations to carry out its own investigations. Notwithstanding this, Brickell says the support of external bodies is still vital to his team’s work. ‘It’s about having expert resources but one of the challenges we face, and this is common across other sports too, is that our powers are limited – we’re a regulatory and non-statutory body that runs horseracing. We haven’t got the same powers that the Gambling Commission or the police have got in terms of evidence-gathering. Whilst we are still able, in most cases, to investigate and prosecute corrupt activity without outside assistance, we occasionally need help from others to obtain elusive pieces of evidence.’

As Edward Carder, a managing associate at Mishcon de Reya and head of the firm’s anti-doping practice, notes, it was only when law enforcement stepped into the FIFA case that the ‘untouchable’ officials finally came within reach: ‘It doesn’t help that often sports governing bodies are in jurisdictions that are ‘light touch’ as well,’ he says. ‘You’ve got the IAAF in Monaco, you’ve got FIFA in Switzerland and it wasn’t really until there was cooperation between the Americans and the Swiss law enforcement agencies that people were really able to get their hooks into FIFA.’

Taking an independent view

Despite these limitations, most lawyers agree that an independent viewpoint – whether from an internally appointed ethics or governance committee or a separate body – is a necessary ingredient for good sports governance.

As Brickell’s experience at the BHA has shown, an impartial view can have a very positive impact on a body’s ability to govern itself. ‘We used an external Challenge Panel during our recent Integrity Review, and I thought that worked very well and really enhanced that process,’ he says. ‘I think that’s certainly the way lots of sports will be moving forward and particularly considering what’s happened in relation to the IAAF, FIFA and the Tennis Integrity Unit, amongst others.’

An objective set of eyes will certainly be vital for the IAAF’s reform, notes Pieth. ‘I believe you need an external supervisor to look at and analyse it and these people should be totally independent and they shouldn’t just be old friends of the organisation,’ he says. ‘That’s what the IAAF has been doing, including Sebastian Coe. He’s been called in as somebody who knows everybody, he’s been in the sport and he’s a hero to many, but remember that Platini had that image too as many fans knew him from the football pitch. You need someone to come in and analyse it and go away after they’ve done their job so they remain totally independent.’

In this respect, ethics boards will continue to play an important role, according to IBA President David W Rivkin. ‘Truly independent ethics boards are an important step in restoring the public’s sense of integrity in the sport,’ he says.

The sports world is now too gigantic and too important to control internally. It should be carefully and impartially watched by independent bodies like ours

Akira Kawamura

IBA Past President and member of the IAAF’s Ethics Board

This sentiment is echoed by former IBA president Kawamura, who sits on the IAAF’s Ethics Board. ‘The sports world is now too gigantic and too important to control internally. It should be carefully and impartially watched by independent bodies like ours,’ he says. ‘Poor governance of any organisation usually ends up with a dominance of power and therefore arbitrary management and we have seen this to be the case in sport. Today’s international sports organisations like the IAAF and FIFA are too large and too important to leave their governance to the arbitrary decisions among their small number of leaders.’

Rivkin also believes the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS), which was set up in 1984 as an independent tribunal to settle sports-related disputes through arbitration, continues to play a significant role in upholding sports’ integrity and actively helps safeguard them from corruption: ‘I do not think that CAS, as administrator, or its panels are likely subjects of corruption. Arbitrators in international cases have only very rarely been found to have engaged in corrupt activity, and the closed panel of CAS arbitrators makes it even less likely.’

If the IAAF, FIFA and other international federations are to clean up their act, Carder believes the power of persuasion may lie with sponsors. ‘The thing that is most likely to change things is commercial pressure – in other words if sponsors decide they’re not going to tolerate the kinds of things that are going to be disclosed and consider withdrawing their funding,’ he says. ‘In a way it would be easier for governing bodies to get their own houses in order rather than legislation to be imposed. I think commercial pressure is one of the drivers to do that.’

This seemed to be the message Adidas wanted to send when reports emerged in January that the clothing brand was ending its sponsorship deal with the IAAF four years prematurely in the wake of the doping scandal.

Andy Korman, a partner at Couchmans who focuses on the commercial aspects of sports law, says the decision to drop the IAAF would be ‘pretty revolutionary’, but was not unheard of. ‘Sponsors don’t automatically have the right to invoke a behavioural clause, but I wouldn’t be surprised if there was something written in the deal, such as an embarrassment or behavioural clause, for them to be able to do that,’ he says. ‘You want the brand association to speak well of the brand and so if something tarnishes your reputation, you’re going to look for a way out. Take the example of Nike, which stuck with Armstrong throughout his cancer battle even when he wasn’t competing. But as soon as it came out he was doping they dropped him like a hot potato.’

The move appeared all the more shocking as Adidas was one of only a handful of sponsors that kept its counsel when FIFA’s corruption story unravelled. Although as Korman and others note, this almost certainly has everything to do with the sports brand’s long-standing history of sponsoring FIFA, and by association the large amount of money that has historically been invested in that relationship, than the likelihood that the clothing brand suddenly developed a moral conscience.

A spokesperson for Adidas declined to confirm to Global Insight that the sponsorship deal with the IAAF has been axed, saying the the company remains in ‘close contact with the IAAF to learn more about their reform process.’

The astronomical cost of restoring reputation

With the ongoing risk of other sponsors pulling the plug, the IAAF will no doubt be looking to restore its image ahead of Rio. Investigations like the ones carried out by WADA’s Independent Commission and those being carried out by the IAAF’s Ethics Board are part and parcel of rooting out the corruption that will ultimately help the federation rebuild its reputation. But they don’t come cheap. WADA confirmed to Global Insightthat it has spent $1.5m on its investigations into the IAAF to date – almost six per cent of the agency’s $26 million annual operating budget.

Although the IAAF’s Ethics Board operates under more limited resources, Beloff is optimistic about its capacity to uphold the integrity of international athletics. ‘The role of the IAAF Ethics Board is significant in assisting, as its name suggests, the premier Olympic sport, in all its manifestations, both on and off the track and field, to maintain the best ethical standards,’ he says. ‘It is not for me to make value judgements on its achievements to date. It is still a relatively new body feeling its way but with a full agenda operating under improved rules, born of its own early experience, which the IAAF Council was swift to accept and endorse.’

The federation unveiled a package of reforms at its most recent Council meeting, which included setting up an ethical compliance group, establishing a ‘timetable for constitutional change’ and formalising an Integrity Unit to try and bring greater independence to the anti-doping process. How effective these reforms will be is still to be answered. ‘Doping and its attendant corruption are the biggest challenges to athletics – and to other sports,’ says Rivkin. ‘If athletes believe that their competitors are doping, they may risk doping in order not to be at a competitive disadvantage. Also, the difference between winning and losing in many sports – especially many of the athletics disciplines – is so narrow, often hundredths of seconds or fractions of inches, that it may be tempting for athletes to close that gap in improper ways… [but] sports lose all their appeal if the public does not believe in their integrity and authenticity.’

Regardless of how the IAAF decides to move forward, McLaren and Young believe the scandals will mark a turning point not just for governance in athletics, but also in other sports worldwide. ‘The overall takeaway for every international sports federation is that they all need to look at their governance structure and processes that they follow,’ says McLaren. ‘They need to stop using the Victorian model and move into the 21st century because most sports have governance structures that are incredibly antiquated, if they have them at all. They don’t have compliance bodies. They have ethics commissions but the ethics commissions can’t really do much if there aren’t effective regimes in which to apply the ethics rules.’

‘There is a tipping point in a sport,’ says Young. ‘It happened in cycling with Armstrong… and it’s probably happened in other sports,’ he says. ‘Once a sport gets there even your most moral athletes suddenly have a moral excuse that it’s ok because everybody is doing it. When you cross that tipping point in a sport, that’s when you’ve got real problems, as true sport is out the window. If I were running an international federation, I’d be doing everything I could to make sure my sport never got to that point.’

Ruth Green is Multimedia Journalist at the IBA and can be contacted at ruth.green@int-bar.org