Expanding reserves and conquering new offshore frontiers: Brazil beyond the Pre-salt

Back to Oil and Gas Law Committee publications

Rafael Baleroni

Cescon, Barrieu, Flesch & Barreto, São Paulo

rafael.baleroni@cesconbarrieu.com.br

Iasmim Carvalho

Cescon, Barrieu, Flesch & Barreto, São Paulo

iasmim.carvalho@cesconbarrieu.com.br

Overview of UNCLOS and maritime boundaries

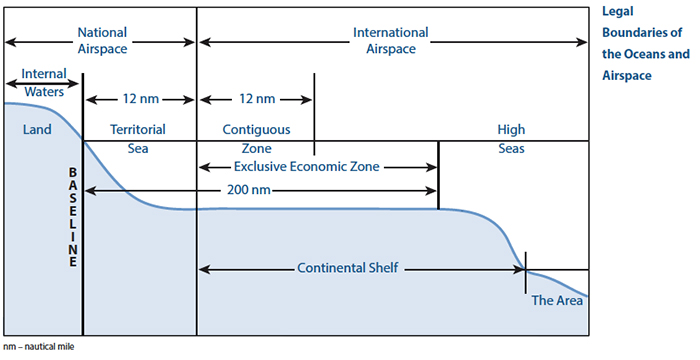

A country’s sovereignty over maritime areas was established by the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). UNCLOS subdivides a country’s sovereignty over maritime areas in four categories or zones: (i) Territorial Sea; (ii) Contiguous Zone; (iii) Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ); and (iv) Continental Shelf, that comprises the seabed and subsoil of the submarine areas that extend beyond its territorial sea throughout the natural prolongation of its land territory to the outer edge of the continental margin, or to a distance of 200 nautical miles (nm) from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured where the outer edge of the continental margin does not extend up to that distance.[1] The zones are summarised on the graphic below.

UNCLOS Maritime zones division[2]

The extent of sovereignty varies in each area. The Continental Shelf, for example, englobes all the other three areas and it is the maximum limit established by UNCLOS for the exercise of sovereignty by a coastal State regarding the exploration and exploitation of natural resources. All the resources located outside of that zone, if not belonging to another state, are considered common heritage of humankind (UNCLOS Articles 136 and 137).

Although initially limited to 200 nm, Article 76 of UNCLOS allows a coastal state to extend its sovereignty to up to 350 nm, if it can demonstrate that its continental shelf extends beyond the 200 nm mark. While the limits up to 200 nm are legally established regardless of geography (other than the internal waters and baseline), the extension of up to 350 nm is a legal consequence of geographical features.

If, by 1982, the offshore exploration of oil and gas was in its infancy, technological development over the following decades changed the situation. With the possibility of gradually reaching a further distance from the coast, deep-water exploration has increased substantially.

Brazil’s maritime boundaries under UNCLOS

Brazil is one of the 119 original signatories of UNCLOS. It was approved by Brazil’s Congress in 1987 and the government ratified it the following year. Before it came into force in 1994, Brazil had already adjusted, in 1993, its internal law to reflect the main aspects of the maritime areas, by means of Law 8,617.

After ratifying UNCLOS, Brazil moved to establish its continental shelf limits, through the Brazilian Continental Platform Survey Plan.[3] This was an ambitious project promoted by the Inter-ministerial Commission for the Resources of the Sea and the Brazilian Navy for the acquisition, processing and interpretation of geophysical and bathymetric data.

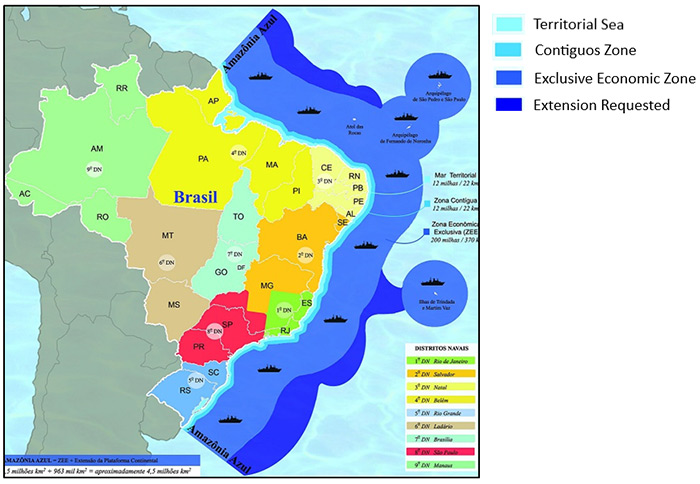

Such measures were taken given the potential importance of resources beyond the 200 nm-limit. In fact, Brazil’s extended maritime boundaries are generally referred to as ‘Blue Amazon’ by its Navy, for its richness in biodiversity, mineral and energetic resources. The map below shows Brazil’s current and claimed maritime areas.

Brazil’s offshore zone[4]

The extension beyond 200 nm depends, however, on approval by the United Nation’s Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS), which is responsible for any claim regarding the extension of the continental shelf. Interested countries must present a submission to CLCS, with information and data as evidence.

Brazil submitted such a request in 2004. After analysing the request, in 2007, the Commission recommended the Brazilian government should present a new submission, considering the reduction of 20 to 35 per cent of the originally requested area. Brazil next presented three partial submissions, regarding the extension of the Southern Region, the Equatorial Margin and the Oriental and Meridional Margins. The Southern Region submission has already been approved, recognising the extension of the Brazilian Continental Shelf beyond the 200 nm. The requests for the Equatorial Margin and the Oriental and Meridional Margins submissions remain under review.

Offshore exploration of oil and gas beyond the 200 nautical mile-limit

While the Brazilian submission for the Equatorial Margin and the Oriental and Meridional Margins remain under review, Brazil’s government has already begun studies towards the exploration and production of oil and gas in such areas. On 10 January 2020, Brazil’s Energy Policy Council set up a Working Group to assess international rules and evaluate whether it was possible to include areas beyond 200 nm in the 17th Oil Concessions Bidding Round, expected to take place in the second half of 2020.

The actions taken by Brazil’s government are strongly based on a precedent set by Canada, which allowed oil companies to explore resources beyond the 200 nm even without the recognition of the extended continental shelf by CLCS. The country was the first UNCLOS party to issue discovery licences on the extended continental shelf,[5] granting Equinor a significant discovery licence and three exploration licences for an area 270 nm off the coast of Newfoundland.[6]

Exploration of oil and gas beyond the 200 nm limit is expected to result in a substantial increase of Brazil’s oil reserves, according to the Ministry of Mines and Energy.

What increases interest in the requested area further, is its proximity to the Pre-Salt Polygon. From a legal perspective, the Pre-Salt Polygon is a zone in which new areas for the exploration and production of oil and gas are to be granted subject to a production sharing regime (Law 12,351). From an economic and geological perspective, it is an area with abundant oil and gas resources, already representing more than 50 per cent of the Brazilian production, according to the National Petroleum Agency (ANP).

Despite the proximity, and potential economic and geological similarity, the extended area (also referred as ‘Pre-Salt Mirror’) is not part of the Pre-Salt Polygon and, therefore, not subject to the production sharing regime. Instead, such areas can be granted under the concession regime, in force since 1997 (Law 9,478). Under the concession regime, the concessionary assumes all risks to explore oil and gas in the block and has full ownership of any production it may develop. The concession regime is simpler and more attractive to oil companies.

Granting concession rights for blocks in areas beyond the 200 nm and still not recognised by CLCS, however, could raise legal questions about Brazil’s authority to do so.

The Continental Shelf is the maximum limit established by UNCLOS for the exercise of a coastal state’s sovereignty. In this aspect, Article 137 of UNCLOS specifically provides that no state shall claim or exercise sovereignty or sovereign rights over any part of the seabed, ocean floor, subsoil thereof, beyond the limits of national jurisdiction (the 'Area') and its resources.

As such, until the extension is formally recognised by CLCS, the area to be granted may be deemed under Article 137 as an area beyond the limits of Brazil’s national jurisdiction.

Further to article 137, states must observe the regulations and procedures of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) in order to claim, acquire or exercise rights over minerals recovered from the area beyond the limits of the national jurisdiction.[7] However, once a country successfully extends the continental shelf, it will have jurisdiction over the increased area, in which case ISA procedures will not need to be observed for the exploration of minerals in that region.

In Canada’s case, while its extension request remains under review by the CLCS, the country issued discovery licences for Newfoundland and Labrador areas with a caveat informing that the boundaries of such licences may be revised to reflect the limits of the Outer Continental Shelf established by Canada, depending on CLCS recommendations.[8] UNCLOS does not require coastal States to halt the activities on the extended continental shelf until the conclusion of the outer limit definition process.[9]

Following Canada’s reasoning, on 14 February 2020, the Working Group concluded that Brazil should move forward with the inclusion of areas beyond the 200 nm in the 17th Bidding Round, which is expected to offer 128 exploratory blocks.

What is yet to be seen is the application of UNCLOS Article 82. It establishes that the coastal state shall make payments or contributions in kind in respect of the exploitation of non-living resources of the continental shelf beyond the 200 nm limit – if the country is not a developing state which is a net importer of the resource. Payments and contributions shall be made annually with respect to all production at the site after the first five years of production. From the sixth to the 12th year, the rate shall increase at one per cent per year, until it reaches a seven per cent plateau.

It is uncertain how the concession documents will allocate this cost. Brazil’s oil legislation establishes the royalties due to the government in the range between five and ten per cent (usually ten per cent offshore), with a potential ‘windfall profit royalty’ (known as special participation) in cases of high production and profitability. In principle, additional payments due to ISA would be a country’s obligation which could not be passed-through to the concessionaire without a legal change. It is important to consider the 17th Bidding Round documents carefully and for the concession agreement to ascertain how risks from potential law changes would be allocated.

Potential future developments

Oil and gas reservoirs do not respect human-set boundaries. They commonly extend beyond areas arbitrarily determined on the surface of the earth. In such situations, oil companies may be required to ‘unitise’ their areas. In general terms, they must agree to jointly developing and producing the resources, and sharing the output, so that resources may be exploited efficiently.

When hydrocarbons extend beyond the borders of a single country, they may also enter into an international treaty governing the joint exercise of authority and sharing output, by means of Joint Development Zone treaties, such as Nigeria and São Tome e Principe; Malaysia and Brunei; among others.

UNCLOS has a specific provision relevant in such a scenario. Article 142 establishes that activities in the Area regarding deposits that lie across limits of national jurisdiction shall be conducted with due regard to the rights and interests of the coastal state which jurisdiction encompasses the other part of the deposits. A system of consultations and prior consent for the exploitation of resources in national jurisdiction exists.

However, UNCLOS considers the matter from the perspective of activities in the Area extending into the EEZ of a country and is quite vague on how activities shall be developed. A potential answer should be consistent with UNCLOS and customary international practice concerning oil and gas reservoirs.

Final remarks

The granting of concessions beyond the Pre-Salt Polygon proclaims a new phase for Brazil’s oil and gas market. Oil companies may benefit from a simpler legal regime (concession), while exploring an area that may be economically and geologically similar to Brazil’s largest oil province. Given the timeframe to commence production, the legal uncertainties that surround the exploration of the extended continental shelf – be it on the Brazilian authority, be it on the payment of royalties – may be settled before it starts. Nonetheless, careful review of the 17th Bidding Round documents and concession agreements is advisable to consider properly the allocation of risks.

The incorporation of the extended continental shelf to its jurisdiction surely will help in Brazil retaining its position as a world-leader in deep-water oil and gas.

Notes

[1] United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), Arts 3, 4, 5, 33, 55, 57 and 76.

[3] The Brazilian Continental Platform Survey Plan was instituted by Decree 95,787, in 1988 and replaced by Decree 98,145 in in 1989.

[5] Aldo Chircop, ‘Implementation of Article 82 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea: the Challenge for Canada’ in The Law of the Seabed, 7 January 2020, Vol 90, p 374.

[7] According to Article 133 of UNCLOS: all solid, liquid or gaseous mineral resources in situ in the Area at or beneath the seabed, including polymetallic nodules, when recovered from the Area.

Back to Oil and Gas Law Committee publications