The blue economy

Elza Holmstedt Pell

Commercial mining of the ocean floor is taking off at scale. Global Insight explores the legal and environmental issues of a new industry that could transform developing nations.

Harnessing the natural resources of the oceans is increasingly seen as crucial to driving global economic growth and prosperity. The United Nations puts the market value of marine and coastal resources at $3tn per year, or about five per cent of global GDP. Its growth is likely to outpace that of the global economy over the next 15 years, says the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Such is the significance of this so-called ‘blue economy’ to global socioeconomic development that in September 2015 the UN adopted Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 14: ‘to conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development’.

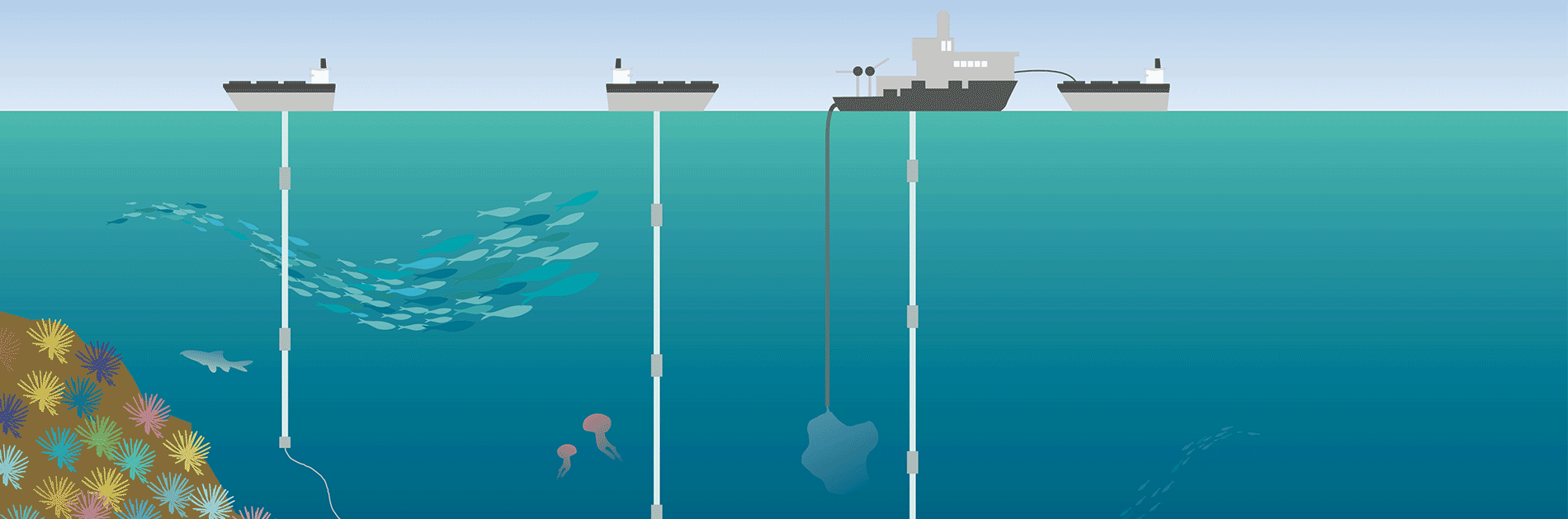

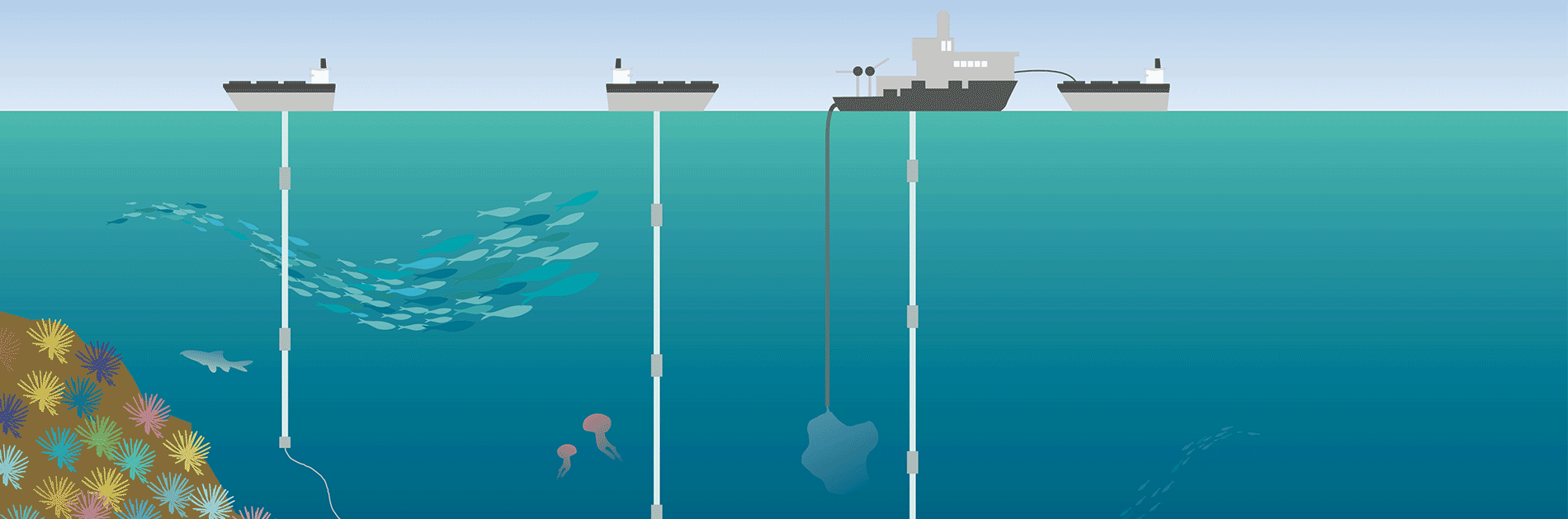

Various activities and industries make up the blue economy, including renewable marine energy, tourism, fisheries and maritime trade. But, if there’s one that’s catching the most attention, it’s deep seabed mining (DSM).

The idea of extracting minerals from the ocean floor is not a new one – global discussions on how to develop and regulate the industry can be traced back to the 1960s. But, while long in the making, most stakeholders agree that DSM is now close to becoming a reality.

The long-awaited start of commercial DSM activities is expected in the next few years, driven partly by soaring demand from mineral-hungry growth sectors like renewable energy, consumer technology and electric vehicles, by the depletion of terrestrial mineral resources, and by progress to regulate the industry.

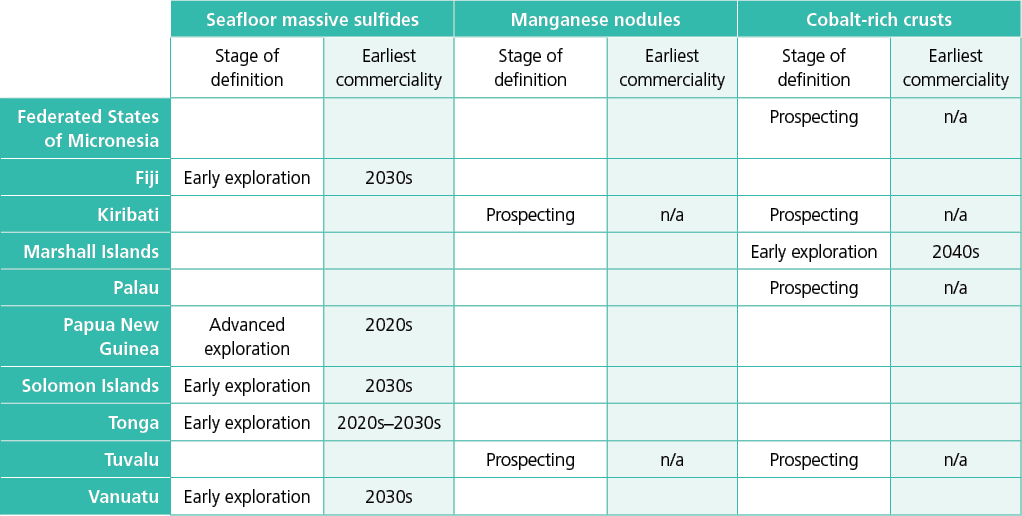

A raft of exploratory DSM activities is already under way, both within territorial and international waters, with many developed states and Pacific island countries (PICs) backing these projects (see table: Pacific early adopters of deep seabed mining). The next step is to move from exploration to actually extracting large quantities of minerals, such as lithium, cobalt, tellurium, copper, manganese and sulphur, from the ocean floor.

Canadian company Nautilus Minerals is tipped to become one of the first to undertake commercial-scale extraction through its Solwara 1 project in the national waters of Papua New Guinea. The initiative has been fully permitted for years, but delayed by funding issues and legal challenges against the state government over the licensing of the project and its impact on local communities.

Nautilus had expected initial production from Solwara 1 to start in the third quarter of next year, but announced on 30 April that it is likely to be pushed back. This is a result of delays in securing the remaining $350m of financing to get the project off the ground, and also resolving issues relating to the production support vessel that will be chartered to Nautilus for Solwara 1. Nautilus Minerals’ Chief Executive Officer, Michael Johnston, told Global Insight the project could still start as early as late-2019, subject to financing, and highlighted that no legal challenge has been lodged against Nautilus.

The difficulties faced by Nautilus – which has a pipeline of planned DSM projects both in national and international waters – highlight some of the challenges associated with this nascent industry. Mining on the seabed is capital-intensive and perceived by many as financially and environmentally risky.

Even so, there’s little doubt that a range of stakeholders – from small DSM specialists, to mining and energy giants, to governments – are keen to start harnessing the valuable minerals on the ocean floor. ‘Onshore mining for lithium, for example, is safe and cheap, but looking offshore is of strategic and long-term importance – it’s a 25–50 year investment,’ says Pablo Ferrara, Counsel at Estudio O’Farrell and Chair of the IBA Public Law Committee.

The majority of such investments are likely to be made in DSM projects beyond jurisdictional waters. Mining activities in the international seabed, also called the ‘Area’, are regulated by the International Seabed Authority (ISA), founded in 1994. A key responsibility of the ISA is to ensure mineral resources in the Area are developed for the benefit of mankind as a whole and all benefits shared equitably among countries, in line with the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

Some of these places are traditional Pacific islands – imagine there’s a mining boom and all of a sudden they’re a new Singapore

Pablo Ferrara

Counsel, Estudio O’Farrell; Chair, IBA Public Law Committee

The ISA has an opportunity to shape and promote best practice in DSM – something that’s missing in terrestrial mining, says Robert Milbourne, an international mining law expert and Managing Director of Mining Standards International. ‘The piecemeal regulation of the mining industry leads to inefficiencies,’ he explains. ‘A typical mining project can be, for example, regulated in Queensland, but operated by a United States company, developed by technology experts in the United Kingdom and export minerals to India or Japan. Then, the minerals go into the supply chain for something sold all over the world – there’s nothing sovereign about that.’

The journey towards exploitation

The ISA has entered into 15-year contracts for exploration activities in the deep seabed with 29 sponsors in total. The majority (16) are polymetallic nodule exploration contracts – mainly for nickel, copper and cobalt – in the 5,000 metre-deep Clarion-Clipperton Zone in the Pacific Ocean.

Exploration contracts must be sponsored by one of the 168 ISA Member States and are subsequently carried out by a contractor. So far, sponsoring states include a mix of major powers like China, France, Germany, India, Russia and the UK, as well as developing PICs such as the Cook Islands, Kiribati, Nauru and Tonga.

All projects are in the exploration stage and no exploitation has taken place. The ISA’s efforts to roll out regulation for exploitation are closely watched. Since 2000, the ISA has issued a mining code and recommendations for contractors, covering prospecting and exploration in the Area.

It’s now developing regulations for exploitation, which set out the regime for sponsoring projects, exploitation contracts, producing environmental impact assessments, and so on. Draft regulations were published last August and are being updated in light of various responses from ISA Member States, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), contractors and other stakeholders.

Some of the exploration contracts awarded by the ISA are getting close to coming to an end and [they’ll] have to figure out how exploitation will take place

Adriano Drummond Trindade

Counsel, Pinheiro Neto

The ISA’s Office of Legal Affairs told Global Insight that the draft exploitation regulations could be adopted and approved by 2019–2020, but that the ISA Council will determine a final timeline.

‘The whole idea of the ISA is to have a legal framework tied up before any [commercial] mining actually takes place,’ says Dr Edwin Egede, a Senior Lecturer in International Law and International Relations at Cardiff University. ‘What’s currently being discussed is ensuring exploitation is done in an environmentally friendly manner. These discussions will go on for a while, and the idea is to involve as many stakeholders as possible, including states, corporations and, importantly, environmental NGOs and NGOs representing the communities being impacted.’

Pacific early adopters of deep seabed mining

Source: Precautionary Management of Deep Sea Minerals, World Bank, 2017

‘There’s an interest on the part of the ISA and nations to get the industry operating and generating profits,’ explains Milbourne. ‘We’re not at a point where the ISA is adopting final regulation [for] the industry, but in the next three to ten years we’ll see operations commence,’ he says, adding that the priority is to put regulation in place to ensure DSM is done responsibly.

The ISA regulations on exploitation will be a crucial starting point for the industry, says Ferrara. ‘They’ve been speaking about this for [decades], but I think now we are at the point of looking at the Apollo 11 taking off into the sky.’

As the DSM industry gains momentum, demand for legal services – still fairly limited at present – will grow, says Adriano Drummond Trindade, Counsel at Pinheiro Neto. ‘It’s a new field that lawyers will have to devote more time to. As the [ISA] regime evolves, demand for legal services will also evolve, so lawyers will become very excited in the future, particularly mining and environment lawyers.

‘It’s interesting that, unlike other mining operations, where the company usually knows beforehand what the exploitation regime is going to be, they don’t [with DSM],’ he adds. ‘Some of the exploration contracts awarded by the ISA are getting close to coming to an end and [they’ll] have to figure out how exploitation will take place – there are very general principles and draft regulations and clauses, but details have not yet been defined.’

The limitations of Pacific island countries

There are questions surrounding whether some of the countries that are early adopters of deep seabed mining (DSM) exploration have adequate resources to fully engage in the International Seabed Authority process and regulate exploration and extraction activities.

A World Bank report, Precautionary Management of Deep Sea Minerals, published in June last year, said the establishment of a regional body, such as a technical service provider or regulator, would be much more efficient than individual Pacific island countries (PICs) building up regulatory capacity. It noted, for example, that Nauru has ‘no technical personnel, ministry or regulatory infrastructure relevant to DSM, and limited legal capacity within government’ and that Tonga’s ‘regulatory expertise and infrastructure for minerals licensing and environmental permitting is very limited’.

Some PICs are more advanced, the report noted. Papua New Guinea, which has several land-based metal mines, has a well-resourced ministry of mineral policy and mineral resources agency also responsible for DSM activities.

The government is, however, facing a legal challenge launched in December 2017. Local community groups, represented by the Centre for Environmental Law and Community Rights, claim they were not properly consulted on the Solwara 1 project, developed in the country’s national waters by Canadian company Nautilus Minerals. Mike Johnston, CEO of Nautilus, said the company has consulted widely in Papua New Guinea.

He added that key documents, such as the environmental impact statement, have been available to the public for years. The project is fully permitted but not yet operational.

‘The reality is that no one really knows what’s best practice for how to sponsor a contractor,’ says a source with experience in mining regulation in developing nations who wished to remain anonymous. ‘It’s a challenge for them, but they’re seeing an opportunity to gain from the sponsorship and they’re trying to do it in a responsible way.’

Some governments looking to sponsor DSM projects are looking to the oil and gas sector, as there might be an overlap in contract models. The different contract models used in deep sea petroleum extraction might be of use, explains Dr Edwin Egede of Cardiff University. A multinational corporation with a subsidiary in a developing state is often a starting point – and this has been seen in the DSM space already in Tonga and Nauru, he adds.

Environmental risks and royalties

As with land-based mining, extracting minerals and precious metals from the seabed does present environmental risks. But, for states and corporates looking offshore for new business, information on how DSM activities could harm marine ecosystems is still scarce.

Major environmental NGOs, including the World Wide Fund for Nature and Greenpeace, have both expressed concern about DSM being commercialised while little is known about the environmental risks.

Dr Rakhyun Kim, Assistant Professor of Global Environmental Governance at Utrecht University, said in an article published in Marine Policy journal last year that the global community should ‘question and scrutinise’ the assumption that DSM is going to benefit humankind as a whole. In line with UNCLOS rules, DSM would only be justified under international law if this is the case. Kim added that the assumption needs to be tested in light of the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which incorporates the 17 SDGs to support global socioeconomic development.

In January, the European Parliament published a resolution on ocean governance in the context of the SDGs. This called on the European Commission and European Union Member States to ‘support an international moratorium on commercial DSM exploitation activities until such time as the effects of deep sea mining on the marine environment, biodiversity and human activities at sea have been studied and researched sufficiently and all possible risks are understood’.

A major barrier for the ISA and states looking to sponsor DSM within or beyond jurisdictional waters will be proving any environmental harm will be limited. ‘It’s already recognised that any exploitation of mineral resources will at some point cause environmental damage,’ says Roberta Danelon Leonhardt, a partner at Machado Meyer and Vice-Chair of the IBA Environment, Health and Safety Law Committee. ‘In the international agenda [in the ISA], there’s a focus on environmental impact assessments.’ These assessments are crucial but, adds Leonhardt, ‘unfortunately we have a lot of work to do’ to get to a stage where all areas that have potential to be exploited have been properly assessed.

Environmental concerns can also be mitigated. For example, in a response to the ISA’s consultation on its draft exploitation regulations, environmental NGO, The Pew Trusts, recommended the ISA exploitation rules could require regional environmental management plans (EMPs) as a prerequisite for an exploitation contract to be issued.

The proposed regulations published last August ‘do not reference strategic or regional EMPs, neither to explain the process for their development nor to describe their relationship with exploitation applications and contracts,’ said the NGO. It also argued that environmental objectives, standards and thresholds for contractors should be made explicitly binding to ensure the marine environment is protected. Another NGO, the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition, has called for the establishment of a standing Environmental Committee as a subsidiary body of the ISA Council.

There’s a focus on environmental impact assessments… unfortunately we have a lot of work to do

Roberta Danelon Leonhardt

Partner, Machado Meyer;

Vice-Chair, IBA Environment, Health and Safety Law Committee

In addition to managing environmental risks, the ISA is working to ensure that benefits from any exploitation activities in the international seabed are equitably shared globally. It’s developing a royalty payment regime that would see profits from mining activities distributed globally. ‘We need clarity around how the royalty will be calculated and what the rate will be,’ says Trindade.

‘This is a complex area of development, so [it’s] understandable, at this stage, that some people are uncertain as to the final mechanics,’ said the ISA, adding that it is working with experts from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to develop a financial model for exploitation contracts.

The ISA is also planning to launch a commercial arm, the Enterprise, which will have the power to explore and exploit minerals in the deep seabed on behalf of the international community, and enter joint ventures to do so with other organisations.

The Enterprise will not become active until commercial DSM is a reality, but Trindade says there are some questions around the future role of the Enterprise. ‘Will it actually be created to operate [mining projects] or will it simply auction areas to third parties? That’s something the ISA will need to work on.’ In its draft five-year strategic plan issued in February, the ISA said it will prepare a study of the issues relating to the future operations of the Enterprise – addressing legal, technical and financial issues – and identify potential approaches to joint venture operations.

Take-up by developing countries

Another priority for the ISA is to provide assistance to developing countries, to encourage their involvement in mining activities on the international seabed.

Pacific islands including Nauru and Tonga are already sponsoring exploration efforts in international waters (see box: The limitations of Pacific island countries). African nations are also trying to get involved. The African Union’s Agenda 2063, a strategic framework for the socioeconomic transformation of the continent over the next 50 years, has a focus on the blue economy, and it’s also developed a more specific Integrated Maritime Strategy to realise the benefits of DSM and other ocean economy activities.

Some 47 African countries are members of the ISA’s regional African Group – and don’t want to fall behind the Pacific states. ‘We’re looking at the Pacific islands to try to learn how they go about it and adapt this to African conditions,’ says Egede, who also serves as an independent expert for the African Union Commission Ad Hoc Expert Group. ‘We can use this as a stepping stone to start getting African sponsors and contractors involved in DSM.’

As any state can sponsor a DSM project – including landlocked nations – there’s plenty of potential, in theory, for developing nations to take part in mining the international seabed. For instance, the ISA and Uganda, which doesn’t have a maritime border, held a workshop last year to discuss ways for African states to participate in DSM activities.

Ferrara, however, is sceptical. ‘Developing countries are not going to go on an adventure in the Pacific Ocean,’ he says. ‘Traditional developed states with a maritime conscience will dominate the industry.’

Costs are, of course, a major hurdle for involving developing nations. As Egede puts it, ‘everyone knows DSM is very capital intensive’.

There are also concerns that DSM activities at scale could adversely impact local communities in some of the smaller, developing states. ‘Some of these places are traditional Pacific islands – imagine there’s a mining boom and all of a sudden they’re a new Singapore,’ says Ferrara. ‘I imagine many people won’t feel comfortable with it – after all, not everyone is eager to exchange their way of life for money.’

Elza Holmstedt Pell is a freelance journalist and can be contacted at elza@holmstedtpell.com