Human rights news from the IBA - April/May 2016

Same-sex marriage: emblematic of gay rights and rule of law issues

Paul Crick

In recent years, same-sex marriage has become emblematic of gay rights, and great progress has been made in a number of countries in the recognition of same-sex unions and same-sex marriage. The Hon Michael Kirby, Vice-Chair of the IBA’s Human Rights Institute notes that: ‘Just as it took centuries and decades to diminish the old racial animosities and gender inequalities, tasks that are as yet incomplete, much progress has been made on LGBTI issues.’ But, he adds, ‘there is still much work to be done.’

Same-sex marriage was first legalised in the Netherlands in 2001. Canada followed, and since then countries in both Europe and the Americas have followed suit, as well as South Africa, to date the only African country to have done so. In 2016, a number of countries around the world have adopted civil partnerships or civil unions and are considering legalising same-sex marriage.

Mechanisms of change

Change has been brought about by a number of means: legislation, via constitutional change overturning discrimination, or simply by referendum reflecting the will of the people. Indeed, popular opinion has often been ahead of the legislature in accepting the concept of same-sex marriage.

Legislation has been the usual way of affecting change. Sometimes that legislation has been pushed through despite strong parliamentary opposition at odds with popular opinion. In Italy, a 2014 Demos poll showed 55 per cent in favour of same-sex marriage, up from 40 per cent in 2009, but the Italian Senate only finally approved a civil union bill in February 2016. This came seven months after the European Court of Human Rights had found Italy had violated the European Convention on Human Rights by not affording same-sex couples adequate legal protection and recognition.

Hostility and violence towards LGBTI people… is as offensive to human rights principles as was racial hatred and apartheid

The Hon Michael Kirby

Vice-Chair of the IBAHRI

Sometimes legislation is inconsistent or incomplete. Within the UK, for example, despite a common perception that same-sex marriage is legal in all four countries – England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales – it remains illegal in Northern Ireland. Although the Northern Ireland Assembly narrowly voted in favour of same-sex marriage last year, the motion was vetoed despite a 2015 Ipsos MORI survey finding that 68 per cent of adults in Northern Ireland believe same-sex couples should be allowed to marry. Other parts of the UK, such as the Channel Islands and Isle of Man, have also introduced civil partnerships but have yet to legalise same-sex marriage.

Constitutional change can be effective in bringing in same-sex marriage. When rewriting its constitution in 1996, post-apartheid South Africa was revolutionary in safeguarding sexual orientation as a human right. In 2005, in Minister of Home Affairs v Fourie,the constitutional court held that failure to recognise same-sex marriage was unconstitutional and the Civil Union Act followed in 2006. Ten years later, the US Supreme Court handed down its ruling in Obergefell v Hodgesthat state-level bans on same-sex marriage were unconstitutional, clarifying what had been a confused pictures across the various states and cities.

Famously, Ireland became the first country to introduce same-sex marriage by referendum, when the proposal to make such marriages legal in 2015 attracted 62 per cent of the votes cast and made headlines around the world. In Australia, federal law bans recognition of same-sex marriages, although registered partnerships are available in some states. When Malcolm Turnbull became Prime Minister in 2015 he stated that a referendum on the issue would be retained after the next election, due by January 2017. It is expected that public opinion will be in favour of same-sex marriages.

Glimmer of hope?

Change still seems very distant in Africa and Asia. ‘Many countries in Asia and the Middle East do not yet recognise the rights of individuals in many areas,’ says David Ryken, Co-Chair of the LGBTI Law Committee, ‘so the rights of LGBTI persons with regard to marriage are very much down on the list of priorities.’

Apart from South Africa, no African country is making any moves towards equality. Many retain colonial anti-homosexual laws and are pursuing intense crackdowns on the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) community, even where such actions affect the whole country and not just the LGBT community. Ryken offers a glimmer of hope though. ‘India is an interesting exception,’ he says. ‘Possibly the LGBTI marriage equality issue can leap-frog over other human rights issues.’

The question of sanctions is regularly raised in the universal periodic review to which all countries are subjected in the UN human rights Council. However, Michael Kirby believes imposition of sanctions by decisions of the United Nations remains some way off. ‘That may come one day when it is fully realised that hostility and violence towards LGBTI people for a variation of nature is as offensive to human rights principles as was racial hatred and apartheid, against which sanctions were imposed after the 1970s.’

Kirby notes however, that ‘homophobia is bad for the balance sheet’ and believes it is multinational corporations that will influence such countries, as the commercial and employment policies they use at head office are exercised in foreign countries and will influence local business practice. He believes that ‘legal firms have to be in the vanguard of setting a good LGBTI example.’

There appears to be a clear split between countries that, recognising changing social and moral values, have moved towards equality in marriage, and large parts of the world which have resisted such change. David Ryken sees the problem in terms of rule of law: ‘Where human rights and the rule of law is already thin on the ground, I do not see there being much movement until there is a fuller recognition that citizens have a right of non-conformity and that states do not have the right to violate individuals and their rights. The fight is really about the rule of law, not the rule by law.’

Call for nominations: IBA Human Rights Award 2016

Every year the IBA recognises a legal practitioner’s outstanding contribution to human rights by honouring their work with the IBA Human Rights Award. Presented on the final day of the Annual Conference, the award recognises notable achievements on promoting, protecting and advancing human rights, the administration of justice and rule of law.

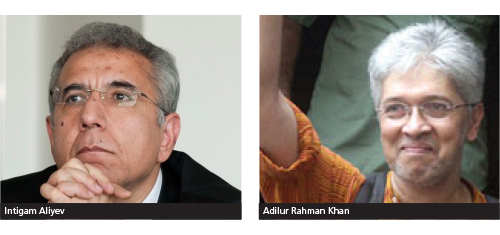

Last year’s winner, human rights defence lawyer Intigam Aliyev, was nominated by his peers for his outstanding and tireless efforts to uphold human rights in Azerbaijan. Unable to collect his Award in person, Aliyev’s work led to a seven and a half year prison sentence and a three-year ban from holding public office, his children accepted the award on his behalf.

Previous winners include: Adilur Rahman Khan, founder and secretary of human rights organisation Odikhar (2014); Somalian Constitutional Law Professor Abukar Hassan Ahmed (2013), presented with the Award for his dedication to the fight for human rights and the rule of law in Somalia; Iranian lawyer Abdolfattah Soltani (2012), presented with the Award for his courage and commitment to the rule of law and human rights in Iran, enduring long-term prison sentences, harassment, and intimidation for providing pro-bono legal counsel to those in need; Colombian lawyer, Ivan Velasquez Gomez (2011), presented with the Award for his commitment to human rights and justice and his work on parliamentary transparency and organised crime; and UK lawyer Clive Stafford Smith (2010), presented with the Award for his commitment to bringing legal rights to the most vulnerable and to those who cannot afford representation, and for his work defending individuals on death row.

For more information on how to nominate someone for the IBA Human Rights Award 2016, visit tinyurl.com/IBAHumanRightsAward2016.

Nominations for this year will close on Tuesday 31 May

New edition of International Human Rights Fact-Finding Guidelines published

In 2009, the IBAHRI, in conjunction with the Raoul Wallenberg Institute, published a set of international human rights fact-finding mission guidelines – the Lund-London Guidelines. These were aimed at improving the accuracy, objectivity, transparency and credibility of NGO mission reports. Increasingly used by courts and tribunals as evidence of facts, the Guidelines were drawn up to set an agreed benchmark of good practice. A document which took years to draft, the final Guidelines underwent strict scrutiny by a multi-stakeholder panel of experts, before publication. The second edition of the Guidelines (available in English, French, Spanish and Arabic) can be downloaded at www.factfindingguidelines.org.

IBAHRI publishes Annual Review 2015 highlighting anniversary year

2015 was a landmark year for the IBAHRI as it celebrated 20 years since its establishment on 5 December 1995. The Institute was founded under the honorary presidency of the late Nelson Mandela, with the aim of promoting and protecting human rights and the independence of the legal profession, under a just rule of law.

2015 was a landmark year for the IBAHRI as it celebrated 20 years since its establishment on 5 December 1995. The Institute was founded under the honorary presidency of the late Nelson Mandela, with the aim of promoting and protecting human rights and the independence of the legal profession, under a just rule of law.

The latest Annual Review provides an overview of the IBAHRI’s recent work and achievements, organised by geographical region.

Highlights include the conclusion of the women’s rights programme in Darfur, the ongoing work to train the Tunisian judiciary on International Criminal and Human Rights Law and the training of Azerbaijani lawyers on human rights law and litigation procedures of the European Court of Human Rights. 2015 was also an important year for the development of the IBAHRI’s presence at the UN in Geneva, where it is undertaking advocacy work. In Myanmar, the IBAHRI took massive steps towards the establishment of the Independent Lawyers’ Association of Myanmar, the country’s first national, independent professional organisation of lawyers. As always, fact-finding missions formed a core part of the IBAHRI’s work, with reports on the rule of law situation in Cambodia and Hungary being published during the course of the year.

Download the Annual Review 2015 at tinyurl.com/IBAHRI-AnnualReview2015. To order a printed copy version of the report, contact hri@int-bar.org.

Turkey: Tahir Elci death must be investigated amid questions over rule of law

Liemertje Sieders

On going obscurity surrounding the death of a prominent human rights lawyer in Turkey in November continues to raise questions about the country’s ability to uphold the rule of law.

A Kurdish lawyer and chairman of the Diyarbakir Bar Association, Tahir Elci was shot dead on 28 November during a press conference in Turkey’s south-eastern city of Diyarbakir. He had been making an appeal for peace in the city, which has been the scene of months of violent clashes between Turkish security forces and members of Kurdish rebel group PKK.

Thousands flocked to Elci’s funeral a day later, but three months on the investigation into his death has yielded no results and violence between Kurds and Turkish forces continues to worsen.

Justice Richard Goldstone, honorary president of the IBAHRI, calls for a transparent and effective investigation into Elci’s death: ‘I join in the call for a thorough investigation into the death of Tahir Elci. It is in the interests of the Government of Turkey to do so.’

Throughout his career, Elci fought to impartially represent victims of violence and violations at the hands of Turkish security forces. He took several cases to domestic courts across the country, and when remedies were unattainable domestically, he appealed to international mechanisms, successfully representing numerous applicants before the European Court of Human Rights in their claims against Turkey.

A memorial event for Tahir Elci took place in London on 27 January, almost two months to the day since the Kurdish lawyer was killed. As noted during the memorial, which was hosted by Amnesty International, Turkey did not have room for the strength of Elci’s voice and several attempts were made to suppress it.

The threats to his safety reached an unprecedented level when he appeared on the CNNTurk show ‘Neutral Zone’ and stated, amongst other things, that ‘the PKK is not a terrorist organisation’. These words provoked a systematic and retaliatory hate campaign which associated Elci with his client’s cause and beliefs.

He was charged with making terrorist propaganda, was briefly detained and began receiving death threats. A few weeks later, while holding making a speech calling for the cessation of violence and for the protection of cultural heritage sites, Elci was shot dead. With tragic irony, as one audience member pointed out during the memorial, ‘Elci died with the call for peace on his lips.’

Elci’s death was a loss to the legal profession and to the country as a whole. Tony Fisher, Chair of the Law Society of England and Wales’ Human Rights Committee and a speaker in the panel discussion held during the memorial, spoke of Elci’s ‘inventiveness and flexibility’ as a lawyer and of his ‘objectivity’.

Turkish lawyer and human rights activist Orhan Kemal Cengiz told of Elci’s relentlessness and how he followed through with cases no matter where they were sent: ‘When I had asked Elci how he dealt with his work psychologically, he responded that his work did traumatise him, but it was only by taking the cases to the courts that he felt rehabilitated from his trauma.’

Baroness Helena Kennedy QC, Co-Chair of the IBAHRI, told Global Insight that ‘Elci spoke for the best of lawyering and showed that lawyers are not just out there seeking remuneration, but are trying to secure justice’.

Elci’s professional achievements, however, as Amnesty International’s Turkey researcher Andrew Gardner noted, constituted only ‘a fraction of who he was’. The memorial’s emphasis on Elci’s warmth and kindness made it clear that his death marked the loss of not only an esteemed lawyer, but also a valued friend.

For some, Elci’s death leaves a question mark hovering over the future of Turkey as to whether it will support or turn away from the rule of law. This uncertainty has been exacerbated by the prevailing atmosphere in Turkey, according to Hans Corell, Co-Chair of the IBAHRI. ‘The situation in Turkey is extremely troubling, making the tragedy of Elci’s death all the more serious,’ he says.

The situation in Turkey is extremely troubling, making the tragedy of Elci’s death all the more serious

Hans Corell

IBAHRI Co-Chair

Despite this grim picture, Kennedy believes that, in time, courage will be restored and voices of dissent will gain strength once more. ‘With his death,’ she says, ‘the baton is being passed onto other lawyers.’ One need only look to Elci’s wife, who despite her sorrow and risks to her own safety, attended the tribute to ensure the voice of her late husband would continue to be heard.

Fisher concluded with a powerful message: ‘The odds are stacked against it. But the odds were always stacked against Tahir Elci. We owe it to him to do something.’

Kennedy stresses the need for governments across Europe to use what power they have to stop this cycle of impunity in Turkey. Goldstone also highlighted the importance of protecting lawyers like Elci across the world who put their lives at risk on a daily basis in order to uphold the rule of law: ‘Human rights lawyers in violent regions of the world courageously defend those less popular with governmental authorities. It is often calculated to dissuade other lawyers from undertaking that kind of work.’

IBAHRI report calls for greater inclusion of lawyers in the UPR process

On 17 March, the IBAHRI’s United Nations programme launched a research report assessing the relevance of the Universal Period Review’s (UPR) recommendations in advancing human rights in the administration of justice. The role of the UPR in advancing human rights in the administration of justice sheds light on why greater inclusion of lawyers in the process leading up to the UPR and thereafter, during the implementation of international recommendations, is worthy of more pressing attention within the international human rights framework.

With the establishment of the UPR in 2006, the UN Human Rights Council sought to address the missing political component; a new peer-to-peer review mechanism putting states in full control of international human rights observations and recommendations. Despite this, the UN system which had previously been criticised for lack of political traction, failed to deliver standardised guidelines on UPR submissions. The result, as highlighted by the IBAHRI’s research, created a gap between recommendations relating to human rights and those relating to legal professionals, such as those endorsed by the UN Special Rapporteur on the Independence of Judges. This has not only affected the mechanism as a whole, but particularly the role of the legal profession in promoting and protecting international human rights on the ground.

Lawyers are at the forefront of human rights defence as those best equipped to monitor and uphold the implementation of recommendations. A ten-country case study provides quantitative and qualitative insights supporting this line of argument. Out of 38,298 recommendations made to the UPR between 2008 and 2014, less than five per cent have related to the independence of the judiciary. By contrast, over the same period, the Special Rapporteur on the Independence of Judges and Lawyers issued approximately 600 communications, addressing over 100 different countries. Violations against the independence of the judiciary, arbitrary sanctions and physical attacks against legal professionals, are just a few examples of reoccurring human rights abuses perpetrated towards the judicial arm of the state.

The IBAHRI report also makes a number of important recommendations, both to states under review and to recommending states, to pay specific attention to the role of the judiciary and professional lawyers’ organisations, and to information coming from their associations. Addressing recommending states in particular, the IBAHRI calls for the separation of powers and judicial independence to be recognised as priority human rights issues. In addition, to lawyers and lawyers’ associations and theOffice of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), the IBAHRI urges better use of existing UN Basic Principles and Rule of Law Indicators to strengthen adherence to international law and norms by creating a benchmark with which to monitor states’ human rights records prior to UPR submission. Overall, if the UPR is to support existing human rights mechanisms it must ensure that its recommendations are implemented and monitored. The legal profession is best equipped to perform this role and should undoubtedly be more involved in this crucial human rights process.

To download the report visit http://tinyurl.com/UPRreport.

IBAHRI starts the year with capacity building programme for young lawyers in Azerbaijan

The continual crackdown on civil society, human rights defenders and journalists in Azerbaijan has significantly reduced the numbers of human rights litigation, as lawyers fear the consequences of defending such cases. This has led to an apparent generational gap among lawyers who are able to work on human rights cases, and recent graduates who have not been adequately trained. Consequently, the IBAHRI-led trainings on human rights law and the litigation procedures of the European Court of Human Rights, particularly aimed at young lawyers and recent graduates from Azerbaijan. Over the course of three days, twenty young lawyers, including some who had already started litigation work, were trained on how to undertake human rights violation cases.