Everywhere in chains

Polly Botsford

Experts say blockchain technology will lead to the second generation of the internet. Global Insight explores the legal and regulatory impact of this latest revolution in technology.

Imogen Heap is a British singer-songwriter who performed at the recent ‘One Love’ concert for the victims of the suicide bombing in the Manchester Arena.

Heap is also an innovator who is fed up with the middlemen of the music industry making money out of, and at the expense of, the artists who actually make the music.

When she released her track, Tiny Human, in 2015, she did so through Ujo Music, a platform connected to blockchain technology.

Through Ujo Music, Heap is able to directly control everything to do with her track, including holding onto the rights and intellectual property, without the need for any middlemen.

The system is also designed such that payments made for the track (either paid for by a listener/fan or by an advertiser who wants to use the track to sell something) can be automatically distributed among the different musicians and producers involved in it at the exact moment at which the song is downloaded or streamed, in order that everyone is instantly rewarded according to their contribution.

For an artist, getting paid for your recorded track sounds like it should be very simple but, in its modern guise, the music industry process is riddled with intermediaries: the record labels, the collection societies that manage the copyright/royalties, and the streaming and downloading platforms.

This problem is mirrored in most walks of life: if we want to transfer an asset to someone we don’t know or someone far away, be it music, money, title deeds or the use of our property, we use a trusted intermediary to make that happen. We use banks, governments, credit card companies, even platforms such as Airbnb, which acts as an intermediary between prospective guest and prospective host. The intermediary verifies identities and uses authorisation processes to ensure that assets are actually transferred.

But, as Heap well knows, intermediaries are costly, because they all take a small percentage of the value of the asset; slow down transactions; can often prevent access completely because they require certain data which some people don’t have; or, as we shall see in the case of financial services, require a complex infrastructure in which to operate (for example, in order to transfer cash, we need bank accounts). Intermediaries are also becoming less secure and untrustworthy, either because of deliberate breaches (witness the manipulation of auctions of United States Treasury securities in 2015) or through hacking and other computer-originated deficiencies.

Second generation internet

Heap and others like her believe that blockchain will revolutionise our lives by securely enabling assets to pass ‘peer-to-peer’ instead of through an intermediary, that we will transfer assets (and value) over the internet as easily as we now transfer information. Blockchain is seen as the second generation of the internet, the technology which will see us shift from the ‘internet of information’ to the ‘internet for value’. By doing so, we will also transform society because, without intermediaries (where all the power is), commerce and beyond will be democratised.

With this distributed ledger, the transaction and the record are the same thing, so we may dispense with a lot of laws that way

Erik Valgaeren

TMT partner, Stibbe Brussels and former Chair, IBA Technology Law Committee

We are still in the nascent stages of the technology, for example, with bitcoin – the most well-known product of blockchain technology – and not everyone shares the optimism that blockchain will be revolutionary. It is clear, however, that it will radically alter the way transactions are managed in every sector, from financial services to insurance, from music to healthcare – and this will have significant challenges for regulators and lawmakers.

Sweeping away laws

It could be that blockchain completely sweeps away certain laws. This is because the technology establishes two crucial elements in a transaction with which many laws currently deal: trust and record.

Blockchain stores digital assets but not in a central place (such as a bank). Instead, they are distributed globally across a network of computers on a vast ‘ledger’. The system builds blocks of all the transactions that have occurred in a certain time period and enters them on the ledger. The transactions are timestamped with what’s been referred to as a ‘digital wax seal’. That is, every single transaction (however small) is recorded in time – and that record cannot be altered in any way. Then the next block of transactions is created and linked to the previous block to form a vast chain. Because of the chain, every new transaction is linked to all the previous transactions and forms an unforgettable record.

Moreover, a block of transactions can only be added to the chain if the transactions have been verified by cryptographic techniques produced by infinitely high levels of computing power. This verification happens very easily and quickly and the effect is such that it is virtually impossible either to defraud or alter a block.

Erik Valgaeren, TMT partner at Stibbe in Brussels and former Chair of the IBA Technology Law Committee, says: ‘A lot of law deals with establishing a record of transactions: the legal proof that the transaction actually happened. But, with this distributed ledger, the transaction and the record are the same thing, so we may dispense with a lot of laws that way.’

Intermediaries also have laws in place to establish trust between two parties, validating information to prevent fraud, for example. But, blockchain technology itself does the verification and validation.

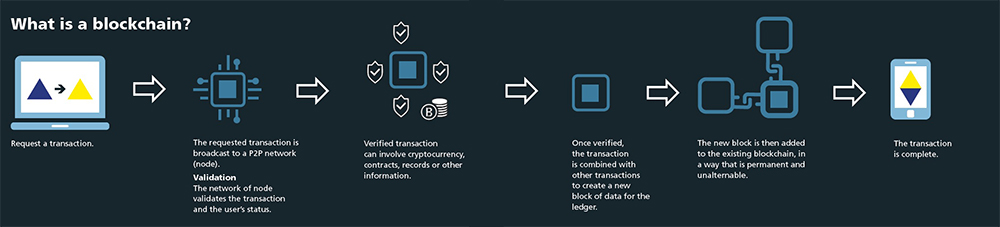

Above: What is a blockchain?

Blockchain paves the way for what are known as ‘smart contracts’. These are computer protocols or codes attached to the blockchain, which ensure that certain terms of a contract automatically self-execute. For example, Slock is developing an application similar to Airbnb, but allowing the host’s property’s door to be unlocked at the point at which the guest pays the deposit and proves their identity. These facts are checked at the actual door via a smartphone and, if everything is in order, the door is unlocked. These steps are self-executing based on the underlying code.

From a legal perspective, the written agreement setting out all these steps has just been dramatically simplified or wiped out completely: legal terms have become code. Clyde & Co partner Lee Bacon says ‘We’re seeing short form agreements that govern who’s responsible for what and what happens when things go wrong. But, we don’t need the pages and pages of terms on how a particular transaction pans out.’

Data: anonymous but still personal

One of the specific areas of law that will need careful examination is data protection. Blockchain will see huge amounts of personal data being processed in any number of areas, such as health information, electronic identification and financial details. This may well gather pace as the technology pushes forward the notion of identification. There are predictions that blockchain will lead to digital ‘tokenised’ identification systems, so that individuals store all their indentification on a ledger. They would then be able to allow different levels of access to the indentification depending on who or what was asking for it.

Though no one can see who exactly is paying for items with a bitcoin, through the ledger you can see where the coins have been used before, and identify someone that way

John Salmon

Fintech partner, Hogan Lovells

‘Even though much data on the ledgers may be anonymous, anonymous does not mean it is not personal data: take, for example, bitcoin,’ says John Salmon, a Fintech partner at Hogan Lovells. ‘Though no one can see who exactly is paying for items with a bitcoin, through the ledger you can see where the coins have been used before, and then identify someone that way.’

But, because blockchains are decentralised, there is no single identifiable entity responsible for processing that data, so who’s responsible for making sure personal data on a blockchain is properly treated? Moreover, blockchains are public and transparent (though blockchains that are private are also being developed – the equivalent of an intranet), so the data may be accessible by absolutely everyone. If there has been a data breach, blockchain’s irreversibility suddenly becomes problematic because you can’t rectify it. This also violates current European data protection laws, which include the right to erasure.

Gabrielle Patrick is Vice-Chair of the IBA’s Leisure Industries Section and Co-Founder and General Counsel for Epiphyte, a company that tries to bridge the gap between traditional banking and cryptocurrencies. She is not overly concerned by these problems. ‘The technical challenge is to obfuscate certain types of data,’ she says. ‘The business solutions have not been mapped into this problem domain – yet.’

Blockchain in action - but beware the blockchains that aren't blockchains

Governments want to engage with blockchain: Estonia has established what is called an X-Road system which is, in effect, a database of citizen data that can be accessed by central government institutions, local municipalities and also the citizens themselves.

Though the system has not been problem-free, it allows citizens to order prescriptions, vote, file tax returns, submit planning applications and so on using a simple ID card which connects with the database.

In the UK, the Land Registry is to trial a ‘Digital Street’ scheme which would allow for land transactions to happen much more easily, as well as allow the Registry to hold more specific and accessible data. This has already been achieved in Georgia and is being tested in Sweden.

Last year, the Commonwealth Secretariat launched a project to develop technology to allow officials of the 52 Commonwealth countries to more easily contact each other regarding potential cross-border criminal investigations.

The Ethical and Fair Creators Association uses blockchain to help start-ups to protect IP rights over new ideas in a similar way that Ujo Music and PeerTracks do in relation to music copyright.

Insurers and reinsurers are getting excited too: American International Group (AIG) and International Business Machines Corp (IBM) piloted a smart contract-based policy for an insured party that allows information to be shared instantly between the main policy in the UK and local policies in the US, Singapore and Kenya, cutting out reams of email chains and paperwork.

Banks are over the moon because they believe the technology will slash back office costs. A consortium of 40 international banks has got together with tech company R3 to develop a system that will enable much more efficient settlement of trades and transactions. This year, R3 secured investment from the banks to the tune of US$107m.

But not all blockchain is really blockchain

As it stands, what R3 is developing is not technically viewed as ‘blockchain’. It is what is known as distributed ledger technology (DLT) which has many of the features of blockchain but isn’t quite the real deal (because, put simply, participants in the ledger are selected and the information on the ledger is more limited rather than participants being anonymous and providing full information). This is not as controversial as it sounds. It is now accepted that there will probably be a lot of DLT developed that isn’t pure blockchain.

‘Innovation flouts the law’

Because the technology is so secure (in itself), much blockchain development work is being done in financial services, from sophisticated trading securities to the basic transfer of cash payments and virtual currencies (bitcoin being the most obvious example).

Indeed, it is in the financial services space that tech optimists become most excited because, instead of having to rely on increasingly expensive and insecure middlemen, simple and cheap peer-to-peer transactions (literally smartphone-to-smartphone) could ‘bank the unbanked’. Individuals in the developing world currently outside of commerce and the global financial system could start to play a part in it.

Abra works in a similar way to bitcoin in that it facilitates payments without the need for a bank account. For instance, Abra allows you to send money to relatives abroad directly and instantly from one smartphone to another at a fraction of the current time and cost for such a service. An example: a woman from the Philippines lives and works in the US. She has a digital cash wallet stored directly on her phone. The digital cash goes straight to her parents’ phone in the Philippines (no bank account required). Her parents can then withdraw the cash via an ‘Abra Teller’, such as a shop in their local area, for a much-reduced fee, say 1.5 per cent. The system is secure because, with a distributed ledger, Abra doesn’t ever take ownership of the cash (and nor does the Teller); that is, it doesn’t go into Abra in one place and then out of Abra in another.

The regulator could access the data directly and develop mechanisms to spot suspicious activity itself

Gabrielle Patrick

Vice-Chair, IBA Leisure Industries Section; Co-Founder and General Counsel, Epiphyte

Patrick envisages huge changes in the laws governing financial services: ‘traditionally, party A transacts with party B through a trusted third party such as a bank or clearing house. With blockchain, party A and party B – who may not know each other – make a transaction directly; that is a completely different arrangement which will need different rules. As we strip away the complex web of transactions, perhaps there will even be fewer rules.’

‘This is deliberate,’ says Patrick. ‘Innovation flouts the law,’ he suggests. ‘That’s what it’s supposed to do: create new pathways that challenge the established way of doing things. These technologies do not follow the letter of the law.’

From sandbox to rule book?

Blockchain presents unique problems for regulators, because it distorts the current model where a trusted (and regulated) third party is used for transactions to take place and it is those third party institutions that regulators rely on to supervise the parties to the transaction.

In the financial services sector, regulators across the world have been grappling with the technology and its potential impact. The general approach appears to be to regulate the specific uses to which blockchain can be put rather than regulate the technology itself. Lawyers argue that regulators should avoid being too prescriptive. ‘We don’t need to figure out today what all the problems will be tomorrow,’ says Valgaeren. ‘We really need a set of standards without too much detail on how those standards are met.’

Most regulators are taking a wait-and-see approach; so far, only two regulators have implemented specific regulations relating to virtual/cryptocurrencies: the New York State Department of Financial Services and Japan’s Financial Services Agency. In the United Kingdom, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) has set up what they term a ‘sandbox’, which is a system whereby businesses develop new (unregulated) products and services and test them in the real marketplace but in a supervised space, and the FCA checks in on what they are doing as they go along. In the last round of sandbox applications, 77 businesses applied and 31 were greenlighted to test their products.

Patrick argues that the regulator’s role could actually change quite dramatically from passive auditor to active participant. ‘At the moment, regulators rely on information that their supervised entities provide them regarding suspicious activity,’ she says. ‘But, with blockchain, the regulator could access the data directly and develop mechanisms to spot suspicious activity itself. This could be an entirely new space for them.’

New problems are old problems

The legal impacts of blockchain will be substantial and wide-ranging. They are not, however, substantively different to what we already have. Many legal issues look quite familiar: problems of governance, contract law, data protection, privacy or intellectual property. ‘Blockchain technology will create new legal problems but within the existing legal architecture, much as the internet did a generation ago,’ says Valgaeren.

Notice, for instance, in the case of smart contracts. At first glance, smart contracts pose interesting questions of enforceability. They are not contracts in the traditional sense of the word (they are essentially code), but they are carrying out the functions of a legal contract. So what happens when a transaction goes wrong? How does one establish offer and acceptance and the other elements of contract law? Because there is no central authority and so no obvious arbitrator for when things go awry, to whom will parties look to sort out a dispute? It looks as if there will be a need for a written agreement that overlays the smart contract, including specific arbitration mechanisms. This is what Patrick calls ‘an evolution of contract law’, rather than the end of it.

Any blockchain-based application raises potential jurisdictional knots: each transaction could fall under the jurisdiction of the various locations of the network, but this seems unworkable. Instead, parties (or platforms?) in a transaction will establish governing law and jurisdiction clauses to provide greater certainty about what laws would apply. It is also worth remembering that everyone was once worried about jurisdictional problems with the internet, but these have not been unresolvable.

For better or worse

Like any new technology, blockchain can be adopted for lawful and altruistic applications but also for uses which are more concerning. In its report, ‘Blockchain technology: Is it building a brighter future?’ the IBA Legal Policy & Research Unit draws attention to some of the negatives: ‘With the potential to develop in as yet undefined ways and into various unregulated areas, is the risk that ethical boundaries… may be crossed.’ For example, bitcoin, which is unregulated and where transactions, though recorded, are anonymous, is believed to facilitate the trade in illegal goods such as drugs or weapons.

It is likely, therefore, that laws and regulations will be developed to confront these uncertainties. ‘We need to match minds so that the business solutions will mature. Regulations will then follow,’ as Patrick neatly puts it.

Blockchain will quickly become something with which all are familiar; lawyers will be part of the evolution that the technology will drive.

Polly Botsford is a freelance journalist and can be contacted at polly@pollybotsford.com

The IBA’s Legal Policy & Reseach Unit has recently published papers on the subjects of blockchain, and disruptive technology and the legal profession. The reports can be accessed here

Blockchain will feature at the IBA Annual Conference in Sydney. On Monday 9 October (0930–1230), there is a table topic discussion ‘Blockchain – the chain unraveled’ organised by the IBA Intellectual Property, Communications and Technology Law Section; and on Wednesday 11 October (1030–1230) ‘Blockchain and its implications regarding business law’.