Our digital future

Simon Fuller, IBA Managing EditorTuesday 11 June 2019

While access to the internet can enable human rights, almost half the world’s population aren’t online. For those that are, so called ‘sovereign internets’, website blocking and other techniques are a growing threat.

The UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – 17 global goals to be achieved by the year 2030 – include, at number nine, to ‘Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization and foster innovation.’ An indicator of success here is to significantly increase access to information and communications technology (ICT), and to further universal and affordable access to the internet for those in least developed countries by 2020.

Houlin Zhao, Secretary-General of the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), a UN agency, has described broadband infrastructure meanwhile as ‘vital country infrastructure, as essential as water and electricity networks’. And, in December 2016, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission declared broadband internet to be a basic telecommunications service – as essential as local landline telephone services.

Given its role in today’s world, some have even argued that internet access is in itself a basic human right. While not going quite that far, in June 2016 the UN Human Rights Council passed a non-binding resolution in favour of the ‘promotion, protection and enjoyment of human rights on the Internet’. The resolution stated ICT’s positive potential for the human race, and considered how internet access enables human rights. For example, the internet is a gateway to a wealth of information – it can ‘facilitate the promotion of the right to education’.

International bandwidth

Despite this recognition, having internet access in 2019 is far from a given – with implications for the exercise of human rights. The ITU’s latest estimates suggest that just over half of the world’s population, 3.9 billion people, are online.

A positive milestone, but news that’s tempered by research from the Web Foundation, published in late 2018, which found a concerning slowdown in growth in the number of people getting online, from a 19 per cent increase in 2007 to six per cent in 2017.

A country’s infrastructure can be a major barrier preventing people from getting online. For instance, a country might lack access to international bandwidth, or there could be problems with infrastructure, such as grid electricity.

Renata Ávila, Executive Director of Fundación Ciudadanía Inteligente, a Chilean non-profit focused on web technologies, says there can be a lack of political will to invest in the connectivity needed. ‘With the wave of privatisation of telephone companies and the commercialisation of airwaves, Universal Service and Access Funds were created in several countries, to connect rural areas to the telephone,’ Ávila explains. ‘Those were rapidly forgotten, underused or repurposed, as landlines became obsolete.’

She suggests using these funds, alongside legal reforms, to fund connectivity, skills and hardware in areas lacking coverage.

In Guatemala, for example, it is highly likely that the person disconnected to the internet will be a woman who cannot afford access because her income is considerably lower than the income of a man

Renata Ávila

Executive Director, Fundación Ciudadanía Inteligente

Where infrastructure is in place, a fear of crime can stop people from using an internet-enabled device, such as a laptop, in public. Citizens might lack digital skills, while some people simply cannot afford to connect. ‘Modern smartphones and hardware like routers, laptops and servers can cost exorbitant amounts, especially when tariffs and taxes are levied on shipping to smaller nations or rural and remote regions,’ says Peter Micek, General Counsel at Access Now, a digital rights advocacy organisation.

Research from McKinsey & Company, published in 2014, identified that of the offline global population, 75 per cent were spread across only 20 countries, and 64 per cent lived in rural areas.

‘Add in the gender digital divide, and other obstacles that result in poor digital literacy and opportunity among disadvantaged groups, and you can see why ICTs are in many cases exacerbating – rather than closing – the gaps between social and economic classes,’ says Micek.

In Guatemala, for example, ‘it is highly likely that the person disconnected to the internet will be a woman who cannot afford access because her income is considerably lower than the income of a man,’ says Ávila. ‘It will be a woman with children, who cannot leave the house to go to the very few places with free access, and who has fewer years of education.’

Ávila describes the problem as ‘augmented inequalities’ – accumulating and making life even more difficult for those disconnected.

For the world’s population who are online, many face a different kind of challenge: disproportionate limitations on what they can access online, and even the temporary loss of any access to the internet. States’ ability – and willingness – to interfere in internet access is a growing concern.

Deterring democracy

On 31 December 2018, the most recent internet shutdown in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) began. The shutdown lasted 20 days and severed both internet access connections and SMS messaging services, affecting a large portion of the population.

It followed the DRC’s tense presidential elections, held on 30 December. The Congolese government justified the shutdown as necessary to keep order while the election results were counted, pointing to ‘fictitious results’ on social media.

The shutdown had ‘a lot of short term consequences, including it being difficult for citizens to communicate, to do business online and to have access to online sources of information,’ says Arsene Tungali, Executive Director at Rudi International, a non-profit based in the DRC. The consequences in the longer term included a large amount of money being lost as a result of the shutdown.

In January 2019 alone, similar shutdowns also took place in Gabon and Zimbabwe, while the Sudanese government targeted social media websites in its own shutdown in December 2018. Advocacy groups including Internet Without Borders condemned the outages.

It is not just a problem in Africa. Access Now’s global civil society coalition dedicated to fighting internet shutdowns, #KeepItOn, has members spread across 68 countries. It tracked more than 185 internet shutdowns in 2018 globally, a figure Micek notes is almost double the 2017 amount. In total it documented 371 shutdowns between 2016 and 2018, including 310 in Asia and 12 in Europe. ‘Official’ reasons given by authorities as to why a shutdown was necessary include technical problems, sabotage – even school exams.

Other states wish to prevent citizens accessing certain types of content online. They think in the long-term, establishing blocking and filtering systems. These too can impact on citizens’ human rights, though sometimes with good reason, as in the case of blocking certain illegal content.

In May 2011, the UN Human Rights Council looked specifically at how states might limit or prohibit citizens’ access to the internet in its Report of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression. Special Rapporteur Frank La Rue expressed concern about states’ practices, including that of disconnecting an individual if he/she violates intellectual property (IP) rights. He considered that cutting off a user, regardless of the reason – including because the user has violated IP law – to be disproportionate and a violation of Article 19, paragraph 3 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, part of the International Bill of Human Rights. Ávila shares this view, noting that ‘it potentially violates regional instruments and most constitutions, at least in Latin America’.

The Special Rapporteur also highlighted how blocking or filtering – such as through China’s so-called ‘Great Firewall’ – can infringe upon citizens’ right to freedom of expression.

The ‘Firewall’ is perhaps the most famous web filtering system, though other countries are moving towards similar models. In India, the government proposed the Information Technology [Intermediaries Guidelines (Amendment) Rules] 2018 (‘Draft Rules’) in December 2018. The Draft Rules are at least partially targeted at tackling disinformation online and fall under Section 79 of the country’s IT Act. They seek to expand the categories of content that intermediaries, such as internet service providers (ISPs), must not host on their platforms. Specifically, the Draft Rules introduce a category of prohibited content defined as that which endangers ‘public health or safety’. Intermediaries will need to proactively deploy automated tools to find and filter out illegal content.

We are heading toward multiple, competing networks of networks, at least technically. This could reduce access to information and infringe the human right to freedom of expression, which applies regardless of borders or mediums

Peter Micek

General Counsel, Access Now

Critics say the Draft Rules could violate the right to free speech and run contrary to the case law of India’s Supreme Court. Julian Hamblin, Chair of the IBA Internet Business Subcommittee and a partner at Womble Bond Dickinson, says that India is moving ‘closer to what is known as “digital authoritarianism”’.

Sovereign internet

The Russian government meanwhile has moved to control the access its citizens have to internet resources originating outside of Russia. A new government bill, dubbed the ‘Sovereign Internet Bill’ in the press, was adopted on 1 May 2019. The bill seeks to protect the functioning of the internet in Russia and was put forward by Russian lawmakers in response to the United States’ National Cyber Strategy. The bill is intended to move Russia towards having a ‘sovereign’ internet for its citizens.

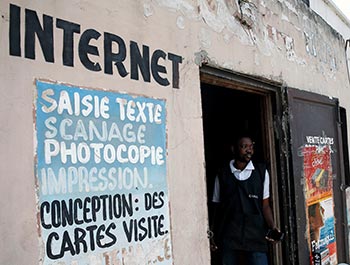

Congolese internet cafe owner Theo stands at the entrance of his empty business in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo, 7 January 2019 © REUTERS/Baz Ratner

Vladislav Arkhipov is Of Counsel in the St Petersburg office of the law firm Dentons. He explains that the bill’s main objective is to provide a legislative framework for ‘centralised administration’ of the internet by the respective federal authority in case of ‘threats to the sustainability, safety and integrity’ of the internet in Russia. To do so, the bill aims to provide infrastructure to keep data exchanges between Russian users within the country; to establish more advanced measures of control over internet traffic; and to ensure that, in the event that it’s not possible to connect to root servers based in jurisdictions outside of Russia, that the internet still functions in Russia.

If threats are identified and ‘centralised administration’ is introduced, this could pave the way for the Russian government to use other instruments for filtering. These may include more precise measures such as deep packet inspection (DPI)-based measures to block internet resources where provided by law, as opposed to relying on blocking measures that utilise a user’s internet protocol address.

‘Introducing DPI blocking on a national scale with appropriate control measures as a result of centralised administration of the network being introduced due to threats to the sustainability, safety and integrity of the internet may result in much more effective blocking,’ says Arkhipov. ‘Ultimately, in the case of an emergency, this may result in a situation where ordinary citizens would have much less access to foreign internet resources and media that are subject to blocking based on the Russian law, in particular on the grounds of the strategic and security considerations of the authorities.’

Given these trends, Micek expects in the long term to see more governments subvert and reduce their reliance on the existing domain name system, instead choosing to create intranets nationally or regionally. ‘We are heading toward multiple, competing networks of networks, at least technically,’ he says. ‘This could reduce access to information and infringe the human right to freedom of expression, which applies regardless of borders or mediums and is best exercised via secure and open access to the global internet.’

A third category of threat to internet access comes in the form of an unequal internet. Users might experience slow or otherwise less-than-perfect internet access as a result of poor network infrastructure, but in other cases it could be a result of discrimination in how network data is handled by the ISP.

The principle of ‘net neutrality’ seeks to avoid this. The concept – that ISPs should treat data on their networks equally, or at least make every effort to do so, regardless of user, website, content, application or method of communication – has been widely fought for, particularly in the EU and the US. The EU’s Open Internet Regulation has applied since April 2016 and means that ISPs in EU Member States can’t block or slow down internet traffic, though there are a number of exceptions to this rule.

In the US, however, net neutrality is less well-protected after the Federal Communications Commission repealed the Obama-era Open Internet Order in 2017. The Order had prohibited ISPs from prioritising certain traffic, for example.

Where traffic discrimination occurs, the quality of internet access an individual experiences can suffer. Indeed, the UN in its non-binding resolution highlighted that when access to the internet is provided, it should be open, ‘nurtured by multi-stakeholder participation’. ‘Around the world, deliberate restrictions on internet access and information happen too often and internet fast lanes are reserved for big corporations that can afford to pay for a preferred treatment. Consequently, smaller voices may be suppressed,’ says Hamblin.

‘Without net neutrality, ISPs would give the “internet that they want” instead of a free internet. This tremendously harms the information access paradigm,’ adds Paulina Silva, Vice-Chair of the IBA Internet Business Subcommittee and Counsel at Chilean law firm Carey. Silva believes that laws enshrining net neutrality, such as that passed by Chile in 2010, establish a framework of transparency and rights for internet users.

The internet as enabler

Not everyone agrees that internet access is a basic human right, but at a national level a number of countries have recognised that they have a duty to provide internet access to their citizens.

‘One may reasonably disagree that such a duty exists,’ says Federica D’Alessandra, Co-Chair of the IBA Human Rights Committee and founding Executive Director of the Oxford Programme on International Peace and Security at the Oxford Institute for Ethics, Law and Armed Conflict. ‘But whether one takes the view that access to the internet is a right in and of itself, or whether one considers access to the internet an enabler of other rights, there is no question that, today, unjustifiably restricting access means diminishing citizens’ participation, and especially where these restrictions are imposed with adverse discriminatory intent on certain groups.

‘States might be found in breach of international human rights law by virtue of the fact that digital freedom is so interconnected with the enjoyment of many rights protected under international law,’ adds D’Alessandra.

Deliberate restrictions on internet access and information happen too often and internet fast lanes are reserved for big corporations that can afford to pay for a preferred treatment. Consequently, smaller voices may be suppressed

Julian Hamblin

Partner, Womble Bond Dickinson; Chair, IBA Internet Business Subcommittee

The UN Human Rights Council’s non-binding resolution on The promotion, protection and enjoyment of human rights on the Internet expressed its deep concern relating to ‘all human rights violations and abuses committed against persons for exercising their human rights and fundamental freedoms on the Internet’. It singled out as very concerning measures ‘that aim to or that intentionally prevent or disrupt access to or dissemination of information online, in violation of international human rights law’.

Courts seem increasingly willing to step in where internet access is threatened. In Zimbabwe, following sporadic internet blackouts in the midst of civilian protests in January 2019, the country’s High Court issued a ruling in which it declared the shutdown illegal and ordered telecom operators to restore access. ‘National courts are beginning to step up and protect individual users and whole societies from this overbearing, unlawful form of government censorship,’ notes Micek. ‘We hope to see regional and international courts soon following suit to hold authorities accountable for network disruptions.’

Ávila says there is a role for strategic litigation to enforce, protect and advance internet rights, including in relation to internet access. She points to a court ruling in Costa Rica, where the Constitutional Court found that, due to the adverse impact of not having access to the internet on fundamental rights such as freedom of expression, access to the internet should be equal to those rights.

In examining how states impose blocking and filtering measures as part of the issue paper, The rule of law on the Internet and in the wider digital world, the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights provided guidance on how EU Member States – including their judiciaries – should operate blocking and filtering regimes while adhering to the rule of law.

The government instructs and the telecom companies blindly execute [internet shutdowns], with no care as to how this decision will affect their users and clients

Arsene Tungali

Executive Director, Rudi International

The Commissioner called for Member States to ensure that restrictions placed on users in their jurisdiction that affect access to content are based on a ‘strict and predictable legal framework regulating the scope of any such restrictions and affording the guarantee of judicial oversight to prevent possible abuses’. Courts must look at whether blocking measures meet the criteria of targeting only the content that needs blocking – while also being necessary, effective and proportionate.

At an individual level, users might deploy technical measures, such as the use of virtual private networks (VPNs), to fight disruptions to their internet access. Tungali’s non-profit has been conducting awareness-building work in the DRC on how internet shutdowns impact citizens’ human rights, and educating people on how digital security techniques can help protect them from the online harms that result from shutdowns.

Further steps could be taken by other stakeholders. Tungali describes the complicity of telecom companies in internet shutdowns, explaining that ‘the government instructs and the telecom companies blindly execute, with no care as to how this decision will affect their users and clients, and how much money they will be losing during that period’.

Tungali would like to see collaboration between telecom companies and their users to help prevent shutdowns, and that ‘clear compensation mechanisms be put in place’ for users affected by shutdowns.

Micek calls upon the offices of the new UN Secretary-General and OHCHR High Commissioner for Human Rights to ‘more closely monitor disruptions’ and ‘assist governments in choosing less restrictive – and more effective – means than censorship to achieve their policy agendas’.

Hamblin suggests that the UN could guarantee a VPN connection to those countries that have been or are politically restricted in relation to citizens’ usage of the internet.

‘International organisations should promote universal access and net neutrality’ and further, ‘ensure that there are no monopolies or oligopolies between ISPs,’ says Raúl Mazzarella, a lawyer at Carey. Mazzarella highlights that these principles might be included in new free trade agreements between countries. He highlights the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, which contains binding commitments on cross-border information flows, as an example.

The alternative – if sufficient action isn’t taken both to get people online and against disruptions to internet access – is succinctly summarised by Tungali. ‘The internet is an enabler of many human rights, including access to information, the right of association, rights to freedom of expression and of assembly,’ he concludes. ‘Whenever the internet is shut down, these rights and others are being taken away from people.’

Simon Fuller is the IBA’s Managing Editor and can be contacted at simon.fuller@int-bar.org