Lava Jato and the winds of change

Ruth Green, IBA Multimedia Journalist

In the wake of the Car Wash corruption scandal, seven Latin American countries are heading to the polls to elect new presidents. Global Insight assesses the implications for rule of law and democracy across the continent.

It’s hard to believe that what began as a relatively routine money-laundering investigation in Brazil soon escalated into a national anti-corruption crusade that captured global attention. However, the sheer scale of the Car Wash scandal, the number of those implicated in the kickbacks for lucrative construction contracts, the impeachment of a former president and incarceration of another, has been more than enough to create a captivating drama on a grand scale.

It soon became apparent that the corruption scandal was not confined to Brazil. The ripples of Lava Jato – as it’s known in Portuguese – have spread far beyond its borders and the fallout has been unprecedented. This was perhaps most obvious in March, when Peru’s President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski suddenly stepped down amid allegations of his involvement in a related vote-buying scandal. He tendered his resignation less than 24 hours before he was due to face an impeachment vote in Congress.

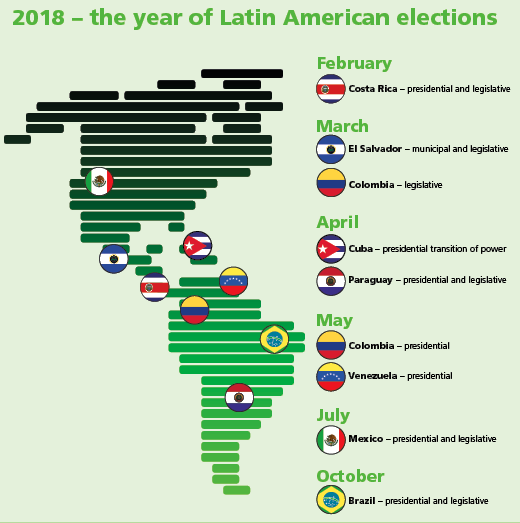

By the end of 2018, 12 Latin American countries from Mexico to Peru will have held elections at different levels: presidential, legislative and municipal. Of these 12, seven – Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Mexico, Paraguay and Venezuela – will elect presidents.

Questions over rule of law will be front and centre of the majority of elections taking place across the region, according to Carlos Braga, Associate Professor at the Fundação Dom Cabral. ‘In some cases, such as Venezuela, the results are pre-ordained and one can only hope that the ongoing crisis will not lead to further violence and social distress,’ says Braga. ‘In most societies, however, rule of law is a hot topic in view of the corruption scandals that have impacted countries like Brazil, Ecuador, Mexico and Peru, to mention just a few. The fight against corruption… typically figures as a key element in strategies to improve governance and the rule of law.’

Although Brazil’s anti-corruption drive and its impact has garnered much attention, too little has been paid to the role of lawyers, prosecutors, the judiciary and the rule of law itself in unearthing the corrupt activities and bringing those culpable to account. In April, after ten hours of fraught deliberation, the country’s Supreme Court finally ruled by six to five that former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva should turn himself over to the authorities and begin serving his 12-year prison sentence for corruption.

Fernando Peláez-Pier, a founding partner of Hoet Peláez Castillo & Duque in Caracas and former IBA President, believes it is particularly significant that the judiciary and wider legal profession have played such a pivotal role in exposing corruption in Brazil and further afield. ‘In countries in which the separation of powers and the independence of the judiciary – fundamental pillars of the rule of law – are still independent, this decision or the resignation of the Peruvian President, for example, are significant,’ he says.

Braga agrees that the domino effect has been particularly noteworthy. ‘What is remarkable in the current anti-corruption efforts is that very powerful entrepreneurs, such as the ex-Chief Executive Officer of the Odebrecht Group, and politicians have been convicted and, in many cases, put in jail after due legal process,’ he says.

This contrasts with Peláez-Pier’s native Venezuela, where President Nicolás Maduro was re-elected for a six-year term on 20 May amid allegations of voting irregularities and as the economy continues to languish: basic food and medical supplies are in scant supply and the rule of law is distinctly lacking. ‘In countries like Venezuela, where the separation of powers and the independence of the judiciary are non-existent, there is no reaction, no mention [of corruption] despite the fact that it is one of the most or the most corrupted administrations in Latin America according to Transparency International,’ says Peláez-Pier.

The severity of the situation facing Venezuelan civil society was highlighted in February when the International Criminal Court’s Chief Prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda, announced her office was opening a preliminary examination to analyse alleged crimes in the country, including use of excessive force by state security forces during mass demonstrations dating back to April 2017. Braga says there has been some willingness to improve the situation, but there are ongoing obstacles. ‘In Venezuela, a country characterised by hyperinflation, that most likely will run above 10,000 per cent in 2018, according to the International Monetary Fund, there is recognition about the importance of improving the rule of law among opposition parties,’ he says. ‘But the ongoing ideological confrontations, the generalised lack of trust, and the dramatic mismanagement of the economy dominate the economic and political debates.’

Protesters march to demand an end to violence, Managua, Nicaragua, April 2018. The banner reads ‘You will not kill’. REUTERS/Oswaldo Rivas

Violence and security still plague Latin America

In April, clashes between anti-government protesters and police in Nicaragua saw dozens killed and acted as a chilling reminder that violence is a problem that shows no sign of abating in many parts of Latin America. A recent report by the Igarapé Institute, a Brazilian think tank focused on security and development issues, found that more than 2.5 million people have been killed violently in Latin America since 2000 – that’s 33 per cent of the world’s homicides. Together Brazil, Colombia, Mexico and Venezuela are home to one in four homicides globally.

Some countries are still recovering from decades of violence. Colombia, which brokered a landmark deal in 2016 ending 52 years of war, is still grappling to cement the peace process. Michael Camilleri, Director of the Peter D Bell Rule of Law Program at Washington, DC-based think tank Inter-American Dialogue, says there is a genuine risk that more violence could ensue. ‘The peace accord is politically unpopular, and it is unlikely the next government of Colombia will bring the same commitment as the current one to the task of implementation,’ he says. ‘The risk is not so much that the peace accord falls apart and the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – Ejército del Pueblo (FARC) return to the jungle, but that a minimalist, underfunded, and poorly coordinated implementation effort fails to address the underlying causes of conflict in Colombia and leads a significant number of former FARC members to migrate into criminal groups – thus perpetuating the violence, albeit in a different form.’

Other countries are also still coming to terms with their past. In El Salvador, during the country’s bloody civil war from 1980–1992, at least 75,000 lives were lost and at least 8,000 people disappeared. In 2016, the country’s Supreme Court ruled a controversial amnesty law was unconstitutional. Previously, the law denied victims of the armed conflict the right to have their cases investigated, but the ruling paved the way for the victims’ families to finally seek justice. To help with this transition period, the International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute (IBAHRI) has visited the country on several occasions since the ruling and brought together a high-level delegation of experts on the rights to justice, truth and historical memory. Together with a wide range of stakeholders, they continue to discuss national initiatives and lessons learned from similar contexts across Latin America and further afield.

While the situations in Colombia and El Salvador are specific, there’s one issue that remains a major contributing factor to much of the violence that stymies progress across the region: organised crime. Brian Weihs, Managing Director and Head of Kroll’s Mexico office, says the co-option of law enforcement by organised crime continues to challenge the rule of law in many countries. ‘This occurs in various parts of the continent, from areas of northern and coastal Mexico to shanty towns in Brazil and rural areas of Colombia and Peru,’ says Weihs. ‘Weak local institutions, such as public security, law enforcement authorities, and municipal or local governments, are unable or unwilling to cope with the violent dominance and corruptive influence of organised crime. The result is high levels of violence and insecurity, exacerbation of extreme poverty and, in some cases, displacement of entire communities to other areas or countries.’

Engaging society

Public confidence in democracy across the region has plummeted in recent years. According to a recent poll by Latinobarómetro, 70 per cent of Latin Americans surveyed were dissatisfied with democracy. However, the anti-corruption efforts in Brazil and some other countries are reaping more positive results: some 35 per cent of those surveyed across the region believe there has been visible progress in the fight against corruption in their countries.

Michael Camilleri, Director of the Peter D Bell Rule of Law Program at Washington, DC-based think tank Inter-American Dialogue, says the way the Lava Jato investigation has been handled does offer a blueprint for other countries in Latin America to tackle corruption head on. ‘The success of the Lava Jato investigation in Brazil has had an enormous impact across Latin America, not least because of the parallel investigations it triggered in several other countries,’ he says. ‘Prosecutors and judges such as Rodrigo Janot and Sérgio Moro are widely admired in Brazil and the broader region for their roles in exposing, investigating and sanctioning systemic corruption.’

However, Paulo Roberto Galvão, Prosecutor on the Lava Jato Task Force, believes efforts by the judiciary and the prosecution service alone will not be enough to change the culture. ‘A huge effort is currently being made to push back the wheel in order to maintain the corrupt status quo that has been revealed in recent years,’ he tells Global Insight. ‘Attempts to pass legislation that would make investigating corruption harder; amnesty laws or other sorts of acts that could prevent investigated people and companies from answering before the judiciary; and media campaigns aiming to shift public opinion against judges, prosecutors and investigators – mere agents trying to fulfil their constitutional roles – have all been put forward as a reaction to the investigations. This constitutes a real challenge to democracy in Latin America, and the population should remain mindful of all of these attempts when facing their own decisions about their governments.’

As the Brazilian Supreme Court’s close vote on Lula’s fate revealed, society remains very divided on how to handle these issues. ‘In Brazil and elsewhere, these nascent but successful efforts to hold the powerful to account have provoked a backlash, and progress remains fragile,’ says Camilleri. ‘Lasting change will require a mobilised citizenry, political renewal, and judicial institutions that are both technically sophisticated and intensely independent. In Brazil, for example, it is essential that prosecutions of corrupt politicians from outside Lula’s Workers’ Party proceed swiftly, in order to counter perceptions of selective justice.’

“A huge effort is currently being made to push back the wheel in order to maintain the corrupt status quo that has been revealed in recent years

Paulo Roberto Galvão

Prosecutor, Lava Jato Task Force

Leopoldo Pagotto, a partner responsible for anti-corruption and antitrust matters at FreitasLeite in São Paulo and Vice-Chair of the IBA Anti-Corruption Committee, says civil society also played a key role in bringing about Lula’s denouement. It was, after all, public pressure that eventually gave the Supreme Court justices cause to abide by their own 2016 ruling that defendants can be imprisoned if a conviction is upheld on a first appeal – as was the case with the former president earlier this year. ‘The judiciary was a driving force behind the anti-corruption enforcement,’ says Pagotto. ‘However, civil society as a whole grew tired and began to pressure courts to keep coherence in some decisions. In view of this scenario, civil society organised itself and legitimately pressed the justices to keep the 2016 approach – their inboxes were flooded with emails, for instance. While some justices were angered with the alleged attempt to intimidate them, I think it was a healthy pressure: the judiciary is not living in a marble tower with no interaction with society. There are always undesired effects of court decisions and the Supreme Court should be particularly attentive to them.’

Summit of the Americas

Brazil isn’t the only country in the region that has clamped down on corruption. It was the central theme of this year’s Summit of the Americas, which took place in Lima in April. During the tri-annual meeting, which brings together heads of government from across the Americas, a consensus was reached on democratic governance against corruption. Fifty-seven specific commitments were made on issues ranging from prosecutorial cooperation, open government and procurement, transparency of beneficial ownership and political finance to the protection of journalists and whistleblowers.

“The success of the Lava Jato investigation in Brazil has had an enormous impact across Latin America, not least because of the parallel investigations it triggered in several other countries

Michael Camilleri

Director, Peter D Bell Rule of Law Program, Inter-American Dialogue

Camilleri is hopeful the so-called ‘Lima Commitment’ will bring about some genuine change. ‘This is significant, especially against the backdrop of recent Summits, which failed to achieve consensus on anything, much less something as central to citizen concerns as corruption,’ he says. ‘To be sure, the Lima Commitment is a statement of intent, not a legally binding or self-executing plan of action. But it is notable nonetheless and provides a roadmap for future action and a basis on which to demand follow-up from governments.’

Pagotto says it could even go further than the Organization of American States’ (OAS) Inter-American Convention Against Corruption, which was adopted in Caracas in March 1996. ‘Everyone is ready to point to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Anti-Bribery Convention (OECD), but the OAS Anti-Bribery Convention pushed the regional legislation towards international best practices and was very significant for levelling the playing field in [Latin America],’ says Pagotto. ‘For sure, the Lima Commitment is far more detailed and daring than the OAS Convention since it had the participation of the enforcers, not only the politicians. In other words, the concrete actions have a more likely concrete impact, even though some of the ideas may take a long time to be implemented. After all, the fight against corruption is above all a fight against pieces of legislation, which unintentionally or not have been used to shield corrupt individuals from the enforcement authorities.’

Panama is another country that has been focused on cleaning up its act. In the wake of the Panama Papers leak, which exposed the sheer extent to which companies and individuals worldwide are concealing their wealth via offshore tax havens, President Juan Carlos Varela announced he was setting up an independent commission to review his own country’s legal and banking systems. His government has since introduced a series of laws, including legislation to improve transparency in the country’s financial system and target large-scale tax evaders, as well as electoral reforms, such as introducing campaign spending limits.

Speaking at an event at the London School of Economics and Political Science, he tells Global Insight: ‘It is not fair to try and define a country by a scandal [involving] one law firm. We are not willing to condemn the image of our country just because of that business and that’s why we’ve passed all these laws and regulations and we created a special commission to make sure that it doesn’t happen again.’

Under the Panamanian Constitution, presidents are obliged to step down after one term, meaning Varela will not stand for re-election in May 2019. Regardless of who succeeds him, he hopes his focus on boosting transparency will prevail. ‘The most important thing is accountability,’ he says. ‘You must ensure that all people that cross public life have the right intentions. In the end, the positions that we have are very important. We manage a lot of wealth, a lot of power, and if we use it for the wrong purposes, then that opens the door to corruption.’ And Varela is clear that corruption in Latin America is by no means confined simply to those involved in Brazil’s Car Wash scandal. ‘It’s many companies, many governments, many people and many candidates,’ he says.

Carolina Zang, a partner at Zang Bergel & Viñes Abogados in Buenos Aires and Co-Chair of the IBA Latin American Regional Forum, believes there is a renewed drive in society to tackle corruption. ‘Corruption was always here in Latin America but the point is that there was not awareness and there was not a desire to make all kinds of anti-corruption enforceable,’ she says. ‘The difference now is everybody wants to make the fight against corruption enforceable. That’s the main change I think our region is facing.’

Zang points to Argentina’s new law on corporate criminal liability, which was passed in December and came into effect in March this year. She thinks laws like this will help ensure the culture around tolerating corruption will disappear for good. ‘What’s interesting about Argentina is a new law was passed recently in order to impose criminal liability on companies for criminal acts,’ says Zang. ‘Before, directors used to be punished, but not companies themselves. It will create awareness of the chain of responsibility in companies, from the most junior employee on your payroll to the most senior executives in management. With time, if every company creates awareness, if every employee is aware of these issues, if everybody receives training, that will create a whole new culture of compliance.’

Despite these glimmers of progress and a raft of other anti-corruption legislation that has swept across the region, independent prosecution is still vital if the success of Lava Jato is to be repeated in other jurisdictions across Latin America, says Brian Weihs, Managing Director and Head of Kroll’s Mexico office. ‘Prosecutors in many Latin American countries have traditionally served at the pleasure of the head of government (national and local) and have had neither the autonomy nor the resources to investigate adequately and prosecute cases of corruption,’ he says. ‘There have been some notable exceptions, for instance investigations in Brazil, which have resulted in numerous convictions of politicians and business leaders, and have spread to other countries, such as Colombia and Peru, and investigations supported by an international commission in Guatemala leading to the jailing of a president. But those investigations have also provided important contrast to several well-known cases of alleged corruption in other countries, which have shown little or no progress towards investigation. So, I would reiterate that one of the greatest challenges to the rule of law in most countries of Latin America is the development and strengthening of investigative and prosecutorial authorities who are independent, and who are seen to be apolitical.’

“In countries like Venezuela, where the separation of powers and the independence of the judiciary are non-existent, there is no reaction, no mention of corruption

Fernando Peláez-Pier

Hoet Peláez Castillo & Duque, Caracas; former IBA President

What Lava Jato and other scandals before it have shown is that there’s a growing need to address impunity across the board, says David Gutiérrez, a partner at BLP Abogados in Costa Rica and Co-Chair of the IBA Latin American Regional Forum. ‘I see the most important rule of law trend in Latin America being how to address impunity of all kinds,’ he says. ‘Not only major political scandals, such as the ones involving former presidents and top politicians, but also those that are more important to citizens in their daily lives, such as simple assaults and robberies, harassment and others. The criminal justice reforms that occurred in Latin America 25 years ago had to do more with an increasing concern for human rights in the region. However, with a growing criminality over the last ten to 15 years, a major concern is how to deal with it efficiently in the justice sector.’

Violence and security are themes that are expected to feature heavily in election campaigns across the region. ‘There has been a growing awareness that corruption and violence are deteriorating the quality of living in Latin America,’ says Pagotto, which is one reason why he believes these issues will dominate the Brazilian presidential elections in October this year. ‘Corruption and violence will be at the centre of the Brazilian political debate in 2018 – forget everything else,’ he says. ‘People are growing tired of the slow reactions of the political system, which is interpreted as an unwillingness to change or tackle the issue of violence and corruption.’

Election interference is another major issue, given recent events in the United States, and some have questioned how equipped Brazil and other countries in the region are with similar political or ideological disruption. Fernanda Barroso, Managing Director and Head of Kroll’s São Paulo office, says there have been some moves to mitigate the spread of misleading information to the electorate in Brazil, but that legislation is behind the times. ‘The current legal framework for dealing with this problem is decades old and is much more related to slander and defamation than to the effects of misleading information in a presidential election,’ she says. ‘One additional challenge here is that the 2004 internet law stipulated strong privacy and freedom of expression protections to internet users.

There is a bill being discussed in the Congress to make intentional spreading of false information punishable by up to two years in prison, but the discussion is still incipient and the bill will probably not be approved before the elections.’

In lieu of any new legislation, Galvão hopes investigations like Lava Jato will help convince voters to take a tough stance on corruption. ‘One very concerning consideration that comes out of these revelations is the fact that the same sort of ill-based relationships take place throughout the region,’ he says. ‘And this happens regardless of the ideological or economic direction of specific governments; that is, the same sort of corruption is seen under left-wing or right-wing governments. What we hope for is that the population of Latin American countries, including Brazil, becomes aware of the damage that corruption brings to their countries, that fighting corruption is something that has to be done regardless of any political or economic ideology, and that the population cannot remain still while waiting for changes to come from the involved politicians. It is up to them to demand and produce these changes.’

Ruth Green is Multimedia Journalist at the IBA and can be contacted at ruth.green@int-bar.org