Fake news

Yola Verbruggen, IBA Multimedia Journalist

Fake news is among the latest phenomena highlighting the law’s struggle to keep pace with technology. Its consequences could pose serious security threats, but fears are mounting that moves to counter it will lead to censorship.

The United Nations Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression David Kaye has called fake news a ‘global topic of concern’. At the World Economic Forum in Davos earlier this year, political and business leaders discussed fake news in several panels. Renowned national and international news outlets repeatedly report about the emergence of it, often focusing on the role of social networking platforms. Universities around the world are researching how to counter the spread of it. As International Bar Association Media Law Committee Senior Vice Chair Robert Balin says, fake news is ‘the term du jour’.

In a meeting of ministers of defence in April, a fake news report that ‘German troops deployed in the country raped a girl and that the commander of the German-led battalion is a Russian agent’ dominated the agenda.

Soon afterwards, a top North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) general warned that more fake news was to come. Some world leaders express their concerns about the spread of fake news and arm themselves against the invasion of troll armies, while others are using it for political gain.

Above: David Kaye, UN Special Rapporteur on David Kaye, UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression

‘Mr President, the media is not fake news’

Fake news, though not a new phenomenon, has become a hot issue since the election of Donald Trump, who has accused several respected news organisations of spreading fake news. Like Richard Nixon before him, he called the media the ‘enemy’. At the annual White House Correspondents’ Association Dinner, Bob Woodward, one of the journalists who uncovered ‘Watergate’, appealed to the President to stop discrediting the fourth estate: ‘Mr President, the media is not fake news’. Trump did not attend the Dinner, the first president not to do so since Ronald Reagan in 1981.

‘I wonder if maybe we’ve overblown what fake news is,’ says Balin, who is a media lawyer at Davis Wright Tremaine in New York City and a lecturer at Columbia Law School. What worries him most is the rhetoric around fake news: ‘It really goes to the role that the press plays in a free society.’

Special Rapporteur Kaye has warned that efforts to counter it could lead to censorship. ‘My concern is that, as much as we might be identifying a particular problem, we’re also in a place where, if we start to regulate this kind of information, it can be subject to real abuse,’ Kaye tells Global Insight.

Various other governments around the world have followed Trump in labelling credible news reports from reputable news sources as fake in order to discredit news they disagree with. In more authoritarian regimes, regulations around fake news are often used as a pretext to arrest journalists. ‘Those kinds of laws are typically designed to undermine the free flow of information and investigative reporting, to undermine dissent and criticism of government, really to undermine everyone’s right to exercise their right to freedom of opinion and expression, which is protected by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and Article 19,’ says Kaye.

In February, six Ivorian journalists were detained and charged with ‘publishing false news’, for which they could serve one to five years in prison, according to Reporters Without Borders, which later reported the group’s provisional release.

In Myanmar, where the violent persecution of the Rohingya Muslim minority has drawn worldwide criticism since a military crackdown in October 2016, the military and civilian government alike dismissed reports about large scale violence and rape. The State Counsellor’s Office released a statement calling the rape claims ‘fake rape’. Yanghee Lee, UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, told Global Insight that it has put the government at risk of ‘appearing less and less credible’.

A newspaper’s only real asset is its credibility. If you’re undermining the credibility of a newspaper, you’re attacking its core asset

Jay Seaton

Former media lawyer and publisher

For one publisher in the United States, the allegation that his paper was spreading fake news was just too much to take. Jay Seaton, who used to practise media law, was flabbergasted when Colorado State Senator Ray Scott attacked The Daily Sentinel of Grand Junction for an editorial it had written. ‘We have our own fake news here in Grand Junction,’ Scott tweeted.

The editorial was, ‘ironically’ as Seaton says, about a bill that would allow greater access to public records in the Colorado legislature and was scheduled to come before a subcommittee – until Senator Scott postponed the hearing. The editorial called on the Senator to set a new date for the hearing and ‘move the bill forward’.

Seaton says the comment on Twitter was more than just criticism. He considered it an attack: ‘A newspaper’s only real asset is its credibility. If you’re undermining the credibility of a newspaper, you are attacking its core asset with false information or a false claim.’ He made public soon afterwards that he was looking to sue the Senator for defamation, in what could have been a landmark case in the legal definition of fake news.

Above: Jay Seaton, Publisher, Daily Sentinel of Grand Junction

‘Could’ have been, because just days before speaking to Global Insight, Seaton had published an opinion on the Sentinel’s website explaining why he would not pursue the case. He had contacted the Sentinel’s lawyers and was told that the merits of his case were sound. The lawyers also offered some further notes; the State Senator could pay for the trial with the taxpayer’s money and the case was likely to be hung up for two years before there would even be a hearing on the merits. ‘That seemed like a non-starter for me,’ Seaton says. Instead, the newspaper will keep doing what it has done since 1893: ‘What we have been doing here for the last 125 years is not easily eroded. We need to continue to do what we do, which is working hard to discover the truth and report it in a reliable fashion.’

For now, this is the route that news organisations choose to take. Newsrooms may not be able to avoid being called ‘a failing pile of garbage’ or ‘fake news’, but lawyers can advise editors and journalists on legal issues to ensure that there is no ground to sue the news organisation.

On a recent working day, editorial lawyers at The Guardian advised on letters in response to the settlement by the Daily Mirror of a number of phone hacking claims, a report about an ongoing criminal trial, and a story about the role of British officials in the massacre of dissidents in Zimbabwe in the 1980s. ‘Lawyers are not acting as fact checkers per se – that is ultimately the responsibility of the author and the editor – but we are part of a backroom team that ensures that everything that is published by The Guardian is accurate,’ says Gill Phillips, the newspaper’s Director of Editorial Legal Services.

Dangerous games

Since his election, President Trump has repeatedly accused the media of spreading false information about him. Yet, during his campaign, fake news regularly circulated about his opponent, Hillary Clinton. Most infamous was the report entitled ‘FBI Agent Suspected In Hillary Email Leaks Found Dead In Apparent Murder-Suicide’. Completely false, the story was, nevertheless, viewed by 1.6 million people.

Above: Mark Stephens, former IBA Media Law Committee Chair

The author of the story was Jestin Coler, a home-based software developer from Los Angeles, once dubbed the ‘king of fake news’. The former fake news creator, outed by the media after publishing the aforementioned story, is now an occasional speaker at some of the most renowned universities in the US, where he talks about an episode of his life of which he is ‘not particularly proud’.

Coler told Global Insighthe was ‘kinda feeling left out’ when his friends wrote stories around the election that went viral on social media. He thought he could do better. It was ‘an ego thing on some level’ that got him into writing fake news, though the money he could earn from ads running alongside his viral stories was also not unimportant. Every day, after clocking out from his day job around 4 or 5pm, he would get back behind his laptop to push out made-up stories through his websites, some less obviously fake than others. He would start ‘sending it around to get people to bite on it’ and then watch the analytics.

One afternoon, he set up the Denver Guardian, on which he would later publish the fake story about the suspicious death of an FBI agent. Coler says he never thought about the possibility of foreign state actors getting involved in spreading fake news (as Russia has repeatedly been accused of doing). When he started to realise that what had started out as ‘goofing around on the internet’ was being held partially responsible for Trump’s election win, it became less fun. ‘It became less humorous as Trump started parroting things that I knew were fake. It changed the game.’

Fake News is:

‘Rather than thinking about what exactly is fake news, (because it’s more of a hash tag than anything else, it’s not a term of art), I think it’s more important to think about the kind of information that is intentionally distributed and intentionally created in order to undermine the public’s right to know and to undermine the public’s ability to discern fact from reality and fact from fiction.’

David Kaye United Nations Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression

‘From time to time, getting a fact wrong in a news story is not fake news. Expressing a view or an opinion that is not shared by the reader or listener is also not fake news. I would say that fake news should be narrowly defined to mean things that are just made up.’

Rob Balin Senior Vice Chair, IBA Media Law Committee

‘The intentional, strategic, deliberate use of not just necessarily misleading but straight up false information to influence dynamics or straight out change outcomes – that is what I define as fake news. The intentionality, directness, deliberateness and “strategic-ness” of the use of that false information is what, in my opinion, draws the line between the fake news that we witness today and the type of misleading reports that throughout history have influenced conflict dynamics in the past.’

Federica D’Alessandra Vice Chair, IBA Human Rights Law Committee & Co-Chair, IBA War Crimes Committee

‘Fake news is, in my view, deliberately manufactured, invented deceptions. Our president began, I think, abusing or misusing the term and applying it to legitimate news organisations such as The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, CNN. And through that use, the term fake news has taken on perhaps a different meaning. It now seems to mean anything you don’t like is fake news. So I don’t know the answer to what is [fake news].’

Mark Stephens Past Chair, IBA Media Law Committee

‘Rather than thinking about what exactly is fake news, (because it’s more of a hash tag than anything else, it’s not a term of art), I think it’s more important to think about the kind of information that is intentionally distributed and intentionally created in order to undermine the public’s right to know and to undermine the public’s ability to discern fact from reality and fact from fiction.’

Jay Seaton Former media lawyer and publisher who considered a law suit against a Colorado senator

‘The Guardian’s readers’ editor has defined fake news as “fictions deliberately fabricated and presented as non-fiction in order to make readers treat them as facts or doubt verifiable facts”.’

Gillian Philips Director of Editorial Legal Services, The Guardian

Coler never got into serious trouble, legally speaking. There were cease and desist scenarios, with which Coler says he always complied. But he quickly learned how to stay within legal boundaries. Apart from copyright infringement and defamation or libel suits, there are no laws that regulate the spread of fake news, several lawyers told Global Insight. ‘There are no laws against fake news per se. There isn’t a remedy for it. It’s just a lie,’ says Mark Stephens, a prominent media lawyer, as well as Immediate Past Chair of the IBA’s Media Law Committee and member of its Human Rights Council. But, he adds, ‘there are limits, and that’s where the law steps in’.

Stephensthinks that regulation is not the solution to the spread of fake news: ‘If there is a problem with fake news and somebody has said something false, then we as members of the public have to call them out for saying something false. And if it is defamatory, we sue them.’

Special Rapporteur Kaye fears that regulation will give too much control to those in power. ‘Whatever government or party controls the government, they will be in a position to define fake news and to regulate the spread of information. We’re already seeing political leaders talk this way, which I think is irresponsible and is really harassing of journalism,’ Kaye says. ‘I think that it’s imperative for political leaders and for governments to avoid heading down that path and instead to encourage people to think more clearly about fiction and fact.’

For Coler, his fake news days are over. After all the attention given to fake news in the press, Google closed down several fake news sites that were using Google AdSense’s paying ad network. Coler’s was the first to go, he says.

But Coler is only one of many people trying to make money by posting content on fake news websites. European countries, such as the Netherlands and France, at election time have also been targeted by fake news websites. Within days of each other, two presidential candidates running against Marine Le Pen of the populist National Front claimed that fake news had been spread about them to sabotage the French election. Documents that circulated online, which Emmanuel Macron says are fake, suggested that he has an offshore account in the Bahamas. François Fillon reportedly complained to prosecutors that satirical newspaper Le Canard Enchainépublished fake allegations that he had hired his wife and children for parliamentary jobs and thereby ruined his chances for the presidency.

There are no laws against fake news per se. There isn’t a remedy for it. It’s just a lie

Mark Stephens

Past Chair of the IBA’s Media Law Committee

Russia especially has regularly been implicated in the creation and spread of fake news, but other foreign governments have not shied away from it. Rodrigo Duterte’s government in the Philippines, which is leading a deadly war against drugs, has issued fake news to discredit its critics. A dark warning was sent earlier this year to Senator Leila de Lima, after she was arrested for her alleged involvement in illegal drugs when she was Justice Secretary. Fake news reports spread that she was in bad health and had attempted suicide. De Lima reportedly saw this as a warning that the government was preparing to kill her and cover it up as a suicide.

Security threat

Because of the impact fake news reports can have on foreign relations, the issue is also high on the agenda of defence ministries and regional security bodies around the world. ‘Fake news or misleading reports can influence the way the conflict is dealt with on the inside, for example in terms of shifts on the battleground,’ says Federica D’Alessandra, Vice Chair of the IBA Human Rights Law Committee and Co-Chair of the IBA War Crimes Committee. This was abundantly clear during a conference organised by the Dutch Ministry of Defence and attended by NATO and other Dutch allies from around the world, where fake news was on the agenda and dominated many unofficial conversations held on the sidelines of the event, says D’Alessandra, who attended the event.

Fake news reports of threats or betrayal can change allegiances or push groups towards more extreme positions in a conflict situation, and can be wielded by either side to influence public opinion. ‘They can create a narrative of the conflict that serves their purposes,’ says D’Alessandra.

Fake news is a serious problem in the conflict in Eastern Ukraine and Crimea, especially regarding the ‘little green men’, a term used to describe Russian special operations forces who wear masks, carry Russian weapons and have no insignias on their uniforms. An organisation called stopfake.org, set up by the Ukraine Crisis Media Center (established by Ukrainian experts in international relations), tries to counter fake news about the conflict in Ukraine. A post from April on the group’s website rectifies a fake story about the death of a monitor of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, a European security watchdog. Reports, allegedly spread on Russian media, blamed the death on shelling by the Ukrainian military. In reality, a landmine caused the vehicle to explode.

A fake story stating that the Israeli Defence Minister had threatened to ‘destroy this country with a nuclear attack’ if Pakistan were to send ground troops into Syria prompted Pakistan’s Defence Minister to warn Israel, via Twitter, that they had nuclear weapons too. Had the story not been credibly rebutted by Israel’s Defence Minister, it could have had far-reaching consequences. The story’s publisher, some fact-checking organisations suggest, regularly spreads fake news.

Trolls and bots

Fake news is nothing new, of course. Misinformation has always been out there. But, the technology now used to spread fake news so swiftly and effectively is new. ‘I think what’s different is social media. Fake news stories get passed on at a lightning speed around the country,’ says Seaton, the publisher who considered a law suit against a Colorado senator.

The development of these networks has led to an interesting new range of terms associated with fake news, such as ‘robotic lobbying techniques’, ‘filter bubble’, ‘Twitter egg’, and a completely new meaning for the word ‘troll’. Most fake news publishers are regarded to be trolls, a person who aims to disrupt, to sabotage conversations on social media platforms and elicit an emotional response from the people they target.

It became less humorous as Trump started parroting things that I knew were fake. It changed the game.

Jestin Coler

Los Angeles-based software developer, once dubbed the ‘king of fake news’

Based on interviews with a large number of trolls, Saiph Savage, an assistant professor at West Virginia University and Director of the institution’s Human Computer Interaction Laboratory, described for Global Insight exactly how trolls work. First, the trolls organise and post together. They meet on platforms such as Discord and Reddit and discuss how to get people to think outside of the box, how to trigger them. Once they have formulated their message, they will go onto networks like Twitter or Facebook and work with influencers – people with a lot of followers – to start promoting ideas. ‘They feel they are going to trigger people,’ says Savage. The same strategy is followed for political messaging as well as for the spread of fake news.

For the distribution of these messages, some trolls have turned to bots, web robots or software applications that perform automated, repetitive tasks. These robots can spread stories or automatically respond to people who use certain key words. Knowing whether you are dealing with a bot or a human is difficult, experts say, and even software designed specifically to identify bots has limited results at best. Obvious give-aways are accounts with only a few followers and no profile photo, that churn out a lot of repetitive information.

There are few laws regulating the use of bots. ‘I feel like now we are coming to a point where it is more of a social norm, and maybe that is better,’ Saiph says. ‘We should define the social norms that might be easier to push than legal regulations, which may become outdated fast.’

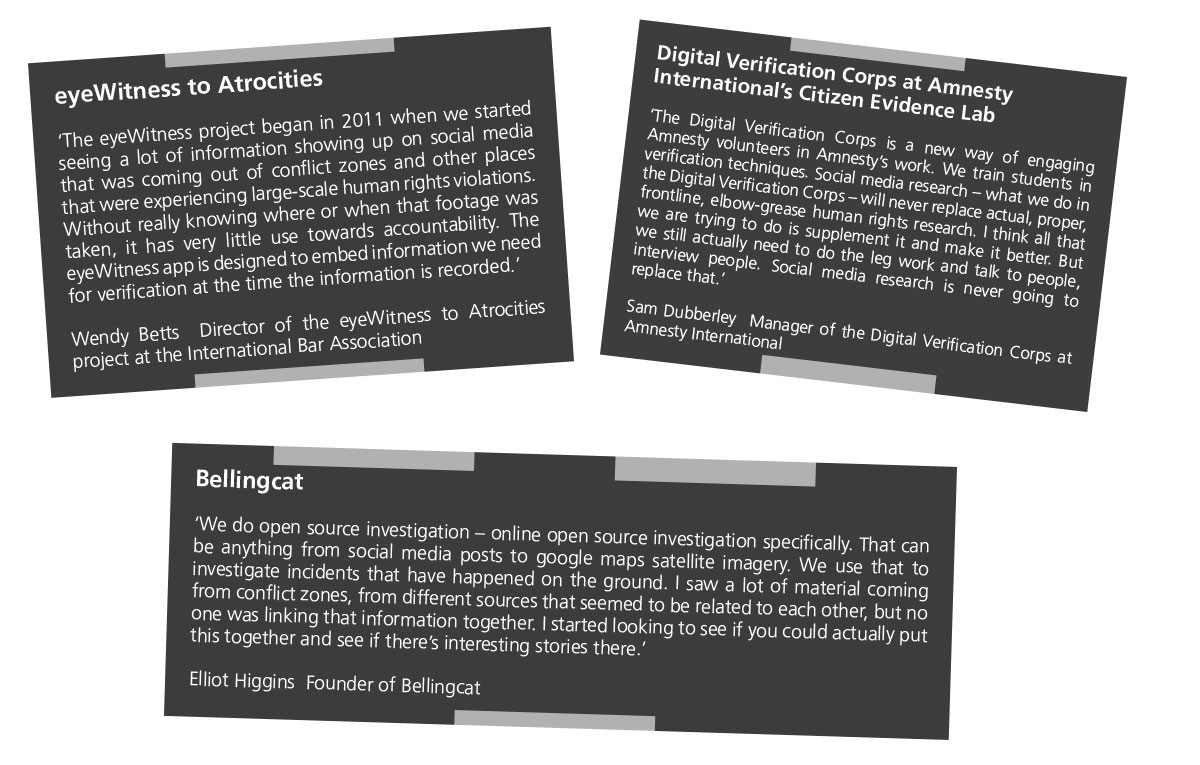

Organisations working on the verification of open source footage

Mexico is one country with considerable experience of bots. In the 2012 presidential race, all three main political parties used bots to spread positive information about their candidates. Every week, one bot-maker says, scores of bots were discovered and a big media outcry would follow. Enrique Peña Nieto won the election and he continues to use bots for the promotion of government policies and to counter or drown out dissent. It has even become a meme – the Peñabot – referring to people expressing positive views about Peña Nieto or his policies.

At the time of the election, Jose Angel Espinoza Portillo was working alongside people with good connections to political parties in the country. The bot-maker found what he calls ‘a new way to evangelise people into the party’ and, because of his connections, he had the opportunity to pitch it to one of the parties (he declines to say which one). The party gave approval for a trial and, after its success, fully implemented the use of bots. ‘It was a revolutionary way of using bots at the time,’ says Espinoza.

He and his team started looking online for people in favour of a certain issue and then analysed the individual and their behaviour online. Then, they’d start generating content, hoping the person they followed would follow them back. After that, real people would start writing content which they put into the system that would then start disseminating it through various accounts and at different times, to avoid being detected as bots. According to Espinoza, he and his team ended up managing 30,000 bots. The bots would rest for just six hours a day ‘because at night its really weird if someone is tweeting’. He claims none of his bots were ever detected because they made them communicate like human beings.

Espinoza is already being approached again by political parties for his services in the upcoming election in 2018, but he has not yet decided whether he will get involved again. He is now working on his own security start-up focusing on artificial intelligence and is proud of what he is doing now, but could be tempted, he says.

My concern is that, as much as we might be identifying a particular problem, we’re also in a place where if we start to regulate this kind of information, it can be subject to real abuse

David Kaye

UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression

Unlike the way bots were used in the US election, Espinoza says his company did not use them to spread fake news. ‘It got popular for fake news during the Trump campaign. We were not spreading fake news; we spread ideas.’

The use of social networks for the spread of fake news, especially in the wake of the US presidential election, has put great pressure on social media companies. There are calls to hold platforms accountable for the content on their pages. The most extreme example comes from Germany, where the German Cabinet recently approved a law that would fine social networks up to €50m for failing to take down fake news.

Stephens thinks this is not a good solution and says the law would be a ‘retrograde step’. ‘Ultimately, I think you have to work on the basis of the polluter pays,’ he says.

Putting social media companies or private actors in charge of defining what is fake news and what kind of information does not belong on their platforms could also be dangerous.

‘If we start down the path of forcing intermediaries to take down content, I think we might end up in a place where we’re starting to lose content that is actually designed to provoke us to think about different policy issues, legal issues and political issues. Ultimately, that will lead to real censorship,’ says Kaye.

He does support the work of academics and fact-checking organisations, and also the involvement of platforms like Facebook, Google, Twitter and other private actors in providing users with tools to make it easier for them to distinguish between fake and legitimate news. But, he warns about the involvement of social networking platforms in this process, ‘those steps themselves also need to be transparent because, essentially, these actors are regulating public space. They’re regulating expression in what many people think of as central public forums, even though they’re owned by private actors.’

Because the same technology can be used and abused for different reasons, it is very difficult to regulate its use. ‘The use and abuse of technology often go hand in hand. I don’t think we were ready for the notion that you could literally, through an algorithm, make up a story with facts that have no relationship to reality. This is society and law running to catch up with technology,’ says Balin. ‘This actually goes beyond law, because it is really about how do we, in a reasonable way, help to guard against insidious behaviour of just making things up…while at the same time making sure that the cure is not worse than the disease.’

Yola Verbruggen is Multimedia Journalist at the IBA and can be contacted at yola.verbruggen@int-bar.org