The climate crisis: are we building back better?

Katie Kouchakji, IBA Environment Correspondent Tuesday 29 November 2022

Spiralling energy prices due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine should be accelerating the transition to low-carbon fuels. Global Insight assesses whether the world is slipping back on its post-pandemic pledges to build back better.

The science on the climate crisis has been clear for several years now. As enshrined in the 2015 Paris Agreement, limiting the average global temperature increase to less than 2°C, and pursuing 1.5°C, compared with pre-industrialised temperatures, would significantly reduce the risks and the impact. Building on that, the historic agreement commits to seeking an emissions peak in the near future. It strives to achieve ‘a balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases in the second half of this century’.

In 2018, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), consisting of hundreds of leading climate scientists from around the world, modelled what a world warmed by 1.5°C would be like and what it means in terms of action. In its 2021 Summary for Policymakers, the IPCC warned that man-made emissions from pre-industrialisation to the present ‘will persist for centuries to millennia and will continue to cause further long-term changes in the climate system, such as sea level rise, with associated impacts (high confidence), but these emissions alone are unlikely to cause global warming of 1.5°C (medium confidence)’.

There’s always so much pressure and focus, especially among environmental activists and climate activists, to keep upping the targets without focusing on implementation

Nathaniel Keohane

President, Center for Climate and Energy Solutions

It went on to say, with a high degree of confidence, that reaching net-zero emissions by 2050 would stop anthropogenic global warming over several decades, and that its models showed emissions needed to be reduced to 40–60 per cent below 2010 levels by 2030 to stay on this trajectory – reinforcing the Paris Agreement’s language and the goals the world is working towards.

Slowly, the race to net-zero began. In her final weeks as UK Prime Minister in 2019, Theresa May pushed through legislation to enshrine in law a net-zero by 2050 goal for the UK – the first G7 nation to do so. Momentum built from there, buoyed by pandemic-driven ‘Build Back Better’ agendas. As of the start of November, 139 countries had net-zero goals either proposed or in law, according to non-profit organisation the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit’s net-zero tracker. These countries represent 80 per cent of the world’s population, 83 per cent of emissions and 91 per cent of global gross domestic product.

But concerns are mounting. As the Covid-19 pandemic drags on, as war rages in Ukraine and as global inflation puts pressure on economies – and thus governments – attention is being diverted from the pressing need to increase efforts to combat the climate crisis. ‘What we have done in the international arena is create a regime, and we nailed down the last bits of that in Glasgow’, says Tom Burke, the London-based Co-Founder and Chairman of think tank E3G, referring to the 2021 climate talks hosted by the UK at which the final rulebook for the Paris Agreement was adopted.

Burke explains that all of the pressures the world faces – the cost of living, Ukraine, global recession – are slowing down the pace at which that regime can be made to work, and subsequently, there’s a risk that it may fall apart. ‘All of the problems with dealing with climate change, all of the really difficult problems, are in the politics – they’re not in the economics or the technology’, he says.

As the community runs out of ways to adapt to the rising Pacific Ocean, the 80 villagers face the painful decision whether to move. Village children pass the time in front of a home next to a flooding sea wall at high tide in Serua Village, Fiji, July 15, 2022. Loren Elliott/REUTERS

When talking about the transition gap, Nathaniel Keohane, President of think tank the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions (C2ES) in Virginia, US, says there are two measures, ‘one tells a really optimistic story, and that’s important, and the other is where we need to focus’. The two gaps he identifies are ambition and implementation. ‘It’s important to keep those straight, because there’s always so much pressure and focus, especially among environmental activists and climate activists, to keep upping the targets without focusing on implementation’, says Keohane.

The ambition gap

‘On the ambition side – and it’s important to recognise there’s a start here – existing commitments under the Paris Agreement, both the [Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs)] to 2030 and also net-zero targets, would give us a better than even chance of staying under 2°C’, adds Keohane. He cites a paper published in November 2021 in the journal Science, which modelled how updated NDC pledges compared with pre-Paris Agreement proposals, and found that the revised 2030 goals provide a stronger likelihood of restricting the rise in average global temperatures to less than 2°C. The paper concluded that this reduces the probability of the worst effects of the climate crisis.

‘The thing [the paper’s researchers] do really nicely is they put their results in terms of probabilities […] so they show existing pledges would have us on track to have a better than even chance of staying below 2°C and would effectively eliminate the chance of being above 3°C’, says Keohane. ‘So really cutting off not just the deep tail, but a lot of the tail – and that’s a big improvement relative to what the trajectory would be in the absence of any policy.’ Keohane attributes this to pressure from activists and the growing awareness of the climate crisis, and believes we’ve succeeded in shifting the conversation so that the pledges that countries have made are now finally at, or least close to, the level of ambition needed.

But not everyone agrees. Bill Hare, CEO and Senior Scientist at the non-governmental organisation (NGO) Climate Analytics, headquartered in Berlin, says that there remains a gap in policies and that things are not progressing fast enough. ‘In terms of emissions, we’re seeing the gap we need to close in 2030 between where policies are heading us and 1.5°C is still big, and if it’s narrowed, it’s only narrowed slightly’, he says. But, he adds, ‘I don’t think we’ve gone backwards, although it might sometimes feel like it’.

A report published in October and co-authored by Climate Action Tracker, a joint initiative between Climate Analytics and the NewClimate Institute, assessed progress towards 1.5°C against 40 indicators across the economy, including buildings, the power sector, transport and forest and land. ‘While we are beginning to see some bright spots, none of the 40 indicators of progress spanning the highest-emitting systems, carbon removal, and climate finance are on track to achieve 1.5°C-aligned targets for 2030’, says the report’s foreword, which was co-signed by Hare.

Measures urgently needed include an accelerated phase-out of unabated coal-burn in the world’s power systems, further improvements in lowering the carbon intensity of cement and for deforestation rates to continue to fall rapidly, the report finds.

When you look at the remaining gap, it’s still enormous, and the progress overall is dwarfed by the amount of work we still have to do

Taryn Fransen

Senior Fellow, World Resources Institute

Measures urgently needed include an accelerated phase-out of unabated coal-burn in the world’s power systems, further improvements in lowering the carbon intensity of cement and for deforestation rates to continue to fall rapidly, the report finds.

Hare warns of the threat from expansions in the liquefied natural gas (LNG) market in response to the Ukraine war, with new production and import capacity being hastily built around the world. Analysis by Climate Action Tracker, released in early November, estimates that the world could have an oversupply of LNG in 2030 of 500 megatonnes – double the amount of total Russian global exports. ‘If that translates into a longer-term commitment and slowdown of decarbonisation, that would be a very big mess for the Paris Agreement target of 1.5˚C’, Hare says.

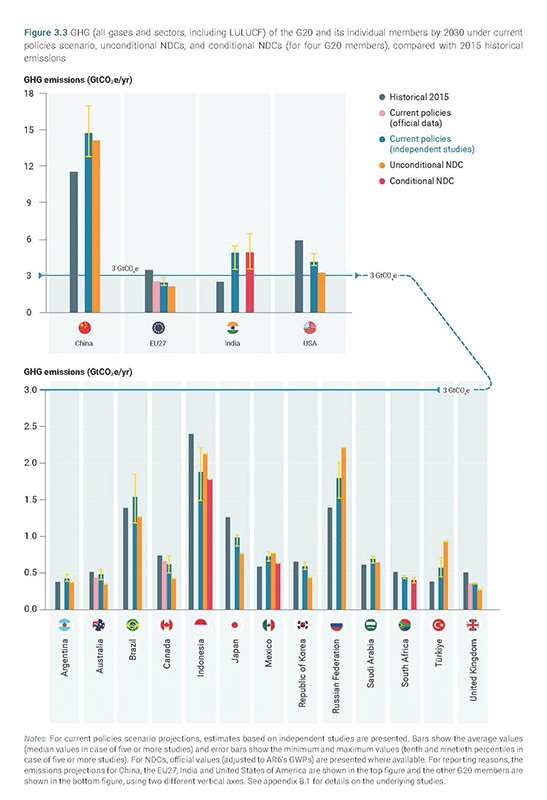

UN Environment Programme’s Emissions Gap Report 2022

Similarly, the 2022 Emissions Gap Report from the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), published in October, finds that current policies translate to a 2.8°C increase by 2100, while full implementation of all pledges made by, and updated since, COP26 in Glasgow in 2021 equate to a 2.4–2.6°C raise. ‘Since [COP26], there has been very limited progress in reducing the immense emissions gap for 2030’, the report says. It quantifies this gap as 15 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (GtCO2e) annually in 2030 for a 2˚C pathway, and 23 GtCO2e for a 1.5˚C pathway.

‘The other number I have is 1.8˚C, if we implement 100 per cent of the NDCs – everything in them, including the conditional [aspects], and we implement the net-zero targets that various countries have put in place’, says Niklas Hagelberg, Coordinator of UN Environment's Subprogramme on Climate Change at UNEP. ‘But in our Emissions Gap report, we say we do not see a credible pathway to those net zero goals.’ He explains that this is because some nations are planning to allow their emissions to peak in the future before reducing. ‘If you think [for example] you want to stop smoking – perhaps it’s best to stop smoking immediately as soon as you hear there’s a problem, instead of first continuing to smoke for another couple of years’, adds Hagelberg.

He cites analysis from UNEP’s 2021 Production Gap report, which tracks planned fossil fuel production, to illustrate his point. He says that last year’s analysis found that countries were still planning to produce 240 per cent more coal, 57 per cent more oil and 71 per cent more gas than what would be consistent with a 1.5°C trajectory. Further, this analysis was undertaken before Russia invaded Ukraine in early 2022, sending shockwaves through the global oil and gas markets and causing governments to scramble for replacement energy supplies.

As the war has dragged on, governments have tried an array of short-term measures to ease the economic pressures on households, including the release of stock from the strategic petroleum reserve in the US and extensions to the lifetimes of coal-powered plants in Germany. But these are just short-term measures, with more structural, long-term systemic changes gathering momentum.

‘The tragic situation in Ukraine, the broader ramifications for the EU, as well as a number of other global events, is accelerating both energy security and climate action’, says Roger Martella, Education Officer for the IBA Energy, Environment, Natural Resources and Infrastructure Law Section (SEERIL) and Chief Sustainability Officer at GE. ‘There is a growing focus on how both goals are mutually compatible: how investments to decarbonise the energy sector at the same time can be deployed to grow energy resilience and a modernised energy infrastructure. So, we’re seeing countries and companies accelerate investments in a more resilient and diverse energy ecosystem, which brings climate change benefits as well.’

‘Energy markets and policies have changed as a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, not just for the time being, but for decades to come’, said International Energy Agency (IEA) Executive Director Fatih Birol at the release of the IEA’s annual World Energy Outlook report in October. ‘Even with today’s policy settings, the energy world is shifting dramatically before our eyes. Government responses around the world promise to make this a historic and definitive turning point towards a cleaner, more affordable and more secure energy system.’

The IEA’s Stated Policies Scenario – which is based on today’s prevailing policy settings – reported that the world would see an increase of 2.5˚C by 2100. While still more than what science says is safe, ‘it is still 1˚C less than the trajectory before the Paris Agreement [was adopted] – in six years, that’s quite a big improvement’, says Joan MacNaughton, a UK-based non-executive director and strategic adviser on climate and energy.

She adds that the IEA’s Announced Pledges Scenario – which assumes all targets announced are implemented in full and on time – brings this to 1.7˚C. ‘If all of those are fully implemented, you’d see emissions peak in this decade and make net-zero more achievable’, MacNaughton adds. ‘But the policies to achieve this are either not in place or have been announced but not acted on.’

Legislation such as the US Inflation Reduction Act – which allocates $370bn in federal funding for clean energy and climate initiatives – and its CHIPS and Science Act, as well as the ‘Fit for 55’ package in the EU – proposals for new EU legislation wherein the bloc and its Member States plan to achieve the EU 2030 climate goals – are examples of more longer lasting transformative policies, which again try to match the ambition of the US and EU NDCs. ‘The Inflation Reduction Act is really the biggest thing the US has ever done on climate change – it will have a big effect on its emissions, but won’t quite get to its target’, says Hare. However, he believes ‘there’s more to come from that Act’.

The implementation gap

But the key is implementation – the second gap Keohane mentions. ‘The biggest thing we need to guard against is complacency and thinking we’ve done it all because we put in place an important first step’, says Keohane. ‘The answer isn’t to say, “oh my gosh we failed, it’s over” – the answer is to say, “we’re going to need to do a lot more”’.

He dismisses concerns that the current crises are distracting policymakers from taking the steps needed to implement changes. ‘The gap between ambition and implementation is one that’s been brewing for a lot longer than Russia’s invasion of Ukraine’, he says. ‘It’s not as if we were on track until February 2022, and then everything went haywire – it’s an endemic issue. And it’s one we should expect, because if we’re setting ambitious targets, we’re going to have to stretch to meet them.’

‘There are signs of progress on the climate crisis, but the pace and scale of the transitions that we are experiencing are not in step with what they need to be in order to avoid the worst impacts of climate change’, says Taryn Fransen, a senior fellow at the World Resources Institute (WRI). Fransen notes there has been progress on the emissions gap, with pledged reductions since the 2015 Paris climate talks being 5.5 GtCO2e lower than previously, ‘which is essentially the equivalent of eliminating the annual emissions of the United States […] but when you look at the remaining gap, it’s still enormous, and this progress overall is dwarfed by the amount of work we still have to do. There is absolutely no excuse for us to be complacent’.

The real energy transition take off needs to come from the private sector

Jonathan Cocker

Sustainability Initiatives Officer, IBA Environment, Health and Safety Law Committee

She also says there’s a need for strong policies to back up and give life to the ambitions leaders are setting. The US Inflation Reduction Act ‘is an example of the kind of transformative policy we need to see’, she adds, noting that if the legislation is fully implemented, it’ll take the US 80 per cent of the way towards its 2030 target of a 50–52 per cent emissions cut, compared with 2005 levels.

‘We’re seeing some promising progress in some areas’, says Fransen. ‘Renewable energy is taking off, costs are falling, the cost of battery technology has fallen dramatically, the uptake of electric vehicles is poised for large growth – those are all very important signs that we are making our way up the learning curve for technology, and that these technologies are now competitive with, if not even better than, from a cost standpoint, fossil fuel alternatives.’

As other jurisdictions begin to implement policies to fulfil their NDCs under the Paris Agreement, costs will decrease, as seen in the case of renewable energy technologies. ‘Once you get the ball rolling and get some momentum going, then that should open doors for countries to feel more confident in making more ambitious pledges under the Paris Agreement’, Fransen says. ‘I don’t think we’ll get more ambitious pledges until we see some evidence of implementation.’

The rollout of renewable energy in the EU has accelerated in response to the war in Ukraine. This acceleration is positive from an implementation perspective, Hare believes. The European Parliament is expected to endorse an acceleration to renewable energy developments as part of its REPowerEU plan, which itself is intended to hasten the bloc’s independence from Russian gas and its domestic development of green energy.

Hare also notes the surge in heat pump installations across Europe, ‘which is good because that gets rid of gas and builds on renewable energy capacity, so is reducing emissions overall’. He also sees positive developments in China, with the country on track for a record rate of growth in its renewable energy capacity. But, he says, ‘the problem is when you add this all up, you just don’t get the emissions bending fast enough, it’s just not widespread enough yet’. India and Indonesia are two places he says need to speed up their transition, while China is also continuing to develop coal capacity – although there is scepticism over whether these coal plants will ever be used, or used at full capacity.

At the Glasgow climate talks in 2021, several jurisdictions including the EU, UK and US announced a Just Energy Transition (JET) Investment Plan for South Africa. This initiative comprises a combination of grants, concessional loans, investments and de-risking measures to leverage private sector capital. A G20 summit in mid-November saw the launch of a JET partnership with Indonesia, while India is reported to be in talks with G7 nations for a similar funding framework.

Kate Logan, Associate Director of Climate at the Asia Society Policy Institute, also warns about the need for an acceleration of the decarbonisation of Asia, as the continent is responsible for half of global greenhouse gas emissions annually, including from many emerging economies – and these are yet to peak. ‘Traditionally the story has been emerging economies and developing countries pushing back on increasing ambition because of the impact of historical cumulative emissions […] but the research that the [High-level Policy Commission on Getting Asia to Net Zero] has commissioned shows that more ambitious climate action is beneficial from an economic development perspective’, she says, referring to a report from the Commission – Getting Asia to Net Zero: Building a Powerful and Coherent Vision – which the Asia Society convened in October.

For example, India could capitalise on the global energy transition by spearheading a development base for green hydrogen and other clean energy technologies, says Logan, which would help in the global pursuit of net-zero as well as creating jobs and benefitting the local economy. ‘There are also challenges, specifically from a finance and technology transfer perspective, but there’s a lot of potential’, Logan says. ‘We’re at a crossroads and we need to be choosing the cleanest path otherwise we’re going to be shooting ourselves in the foot going forward.’

People play Sunday league amateur football matches on parched grass pitches during a heatwave, with the central London skyline seen behind, at Hackney Marshes, in London, Britain, August 14, 2022. Toby Melville/REUTERS

Jonathan Cocker, Sustainability Initiatives Officer of the IBA Environment, Health and Safety Law Committee and a partner at Borden Ladner Gervais in Toronto, also flags the finance gap as a challenge. ‘Worldwide, there’s a great deal of government commitments around funding, but when you look very closely at the private sector, there is still a lot of hesitancy around those funds’, he says.

Cocker identifies a role for governments to be a sort of third-party assurance for these projects and highlights that this hasn’t really been assumed worldwide. Governments filling this role will give the private capital the confidence that there’s a backstop in the event that these projects don’t proceed in the way that the funding has modelled them, says Cocker, who adds that ‘the real energy transition take off needs to come from the private sector’.

GE’s Martella identifies three trends from the COP27 climate talks in Egypt that he believes will be transformative. First, he sees emerging economies playing more of a role in climate solutions and demonstrating how to decarbonise while still providing an increasing amount of reliable, affordable and clean energy. ‘Second, we’re seeing rapid innovation in technology that’s enabling both decarbonisation and resilience progress this decade’, he continues. ‘Third, we’re seeing an increasing importance on public-private partnerships, and coalitions of companies, governments, NGOs, and others coming together in a “sum is greater than the parts” approach to solving for climate.’ Martella says that these three catalysts together are likely to accelerate climate action this decade beyond anything we’ve seen in the past.

Closing the gaps

While the COP27 talks focused on implementing the Paris Agreement and the NDCs, given the 2015 Agreement’s bottom-up structure, it still ultimately falls to individual nations to keep their promises and narrow the implementation gap. There is no one single solution, however.

We need to throw everything we can at the problem, believes C2ES’s Keohane. He says that ‘we need economy-wide approaches such as a price on carbon and we need regulatory approaches, we need sectoral approaches that focus on electrical vehicles and decarbonisation of industry, agriculture, buildings, etc, we need other innovative ways to use government, whether that’s [via] procurement or government grants that leverage private sector funding like a green bank or loan programmes […] we need deep and broad investment in technology innovation and deployment. The answer to which policies do we need is, it’s everything’.

Climate activists take part in a protest during the COP27 climate summit, in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, November 17, 2022. Mohamed Abd El Ghany/REUTERS

Economic incentives, such as emissions trading or carbon taxes, can help. Keohane points to the EU, which has led the way with its emissions trading system. This is applicable to industry and power and is expanding to other sectors, including transport. It reduced the bloc’s emissions by 35 per cent between 2005 and 2019. He adds that the US Inflation Reduction Act, which he describes as a ‘massive set of incentives in the form of tax credits and subsidies’, is also going to be very important.

Keohane stresses that ‘carbon pricing is not a silver bullet’, however. On this theme, Burke from E3G explains that ‘no one knows what the right price of carbon is. The only way you find out what’s the correct price of carbon is when you’ve got it out of your economy, and whatever it cost you to do that was the price of carbon’.

Reaching net-zero also means a need for emissions removals, which European carbon market veteran Louis Redshaw, CEO and Founder of Redshaw Advisors in London, says are currently too costly for most corporates, particularly as such investments are currently done via the voluntary carbon market. ‘We have to have legislation, but some politicians are afraid of legislation – and some politicians don’t even believe we need legislation or any carbon cap’, he says. ‘The irony is, in 2050, there has to be legislation that says that any tonne [of emissions] that’s put into the atmosphere, a tonne has to be taken out somewhere else.’Redshaw suggests that no one with any meaningful carbon footprint is going to volunteer to pay €100 per tonne to get a removal, ‘they’re only going to do it if they’re forced’.

Beyond carbon pricing, MacNaughton also sees regulation driving change for businesses, particularly mandatory climate-related financial risk disclosures, which are now in force in jurisdictions including the UK and New Zealand, for both publicly-listed companies and those in certain sectors. ‘To comply with the government’s governance requirements, you need to be reporting on it, and if you’re reporting on it, you don’t want to be telling a story of you not doing anything’, she says.

Corporate awareness and action to reduce emissions footprints has risen dramatically, with MacNaughton noting that the business turnout at the Glasgow climate talks in 2021 was the highest she’d ever seen and was evidence of the issue being taken more seriously. Some businesses have spearheaded sector-based initiatives, such as The Climate Group-led RE100 – which aims to source 100 per cent of power from renewables – and this also helps galvanise change. ‘There’s a huge number of initiatives bringing in other actors, which forces governments to uphold NDCs’, she says.

In Asia, there’s a challenge in terms of political will that needs to be overcome before any meaningful progress takes place to close the gap. For example, Logan says Indonesia has a huge potential for solar power yet is facing significant policy and regulatory barriers. China, too, could benefit from reforms, such as bringing its subsidisation of the coal industry to an end and reforming its grid to make full use of the renewable energy capacity it’s bringing online. ‘One of the ways to accelerate the uptake of renewables in the grid and to benefit from it is basically power sector reform, so that clean power can be sold more easily across provinces and at the actual price so that the price of coal is not kept artificially low’, says Logan.

‘If we can break through some of these barriers, that then creates the political will in the short term – it is there at a high level, especially from a net zero perspective in the mid and long term, but now that needs to translate into immediate action, which is always difficult when you look at all the different conflated challenges right now in terms of recovery from Covid [and the] economic downturn’, Logan adds. ‘Leaders have a choice, and that choice is reflected in the decisions they’re making today. If we want to narrow that gap, we need them to take the more decisive action in the near term.’

‘The people who are really not getting it are the politicians’, says Burke. ‘The public discourse has grown and shifted in the past decade’, partly because the impact of the climate crisis is increasingly being felt around the world. ‘Politics is difficult – you’ve got to get a lot of people to agree to do something […] facts change policy, and narratives change politics’, he adds.

‘CO2, once you put it in the atmosphere, stays there, so the amount of warming we experience is a function not only of emissions in any given year but also cumulative emissions’, says the WRI’s Fransen. ‘If we’re not making that [2030 target] and we still want to limit warming to 1.5°C – which we absolutely should do – we are really backing ourselves into a corner for post-2030 because we’re going to have eaten up all the carbon budget.’

Katie Kouchakji is a freelance journalist and can be contacted at katie@kkecomms.com

Image credit: Martin Valigursky/AdobeStock.com