The Russian assault on Ukraine’s heritage

Andriy Kostin, Prosecutor General of UkraineWednesday 28 February 2024

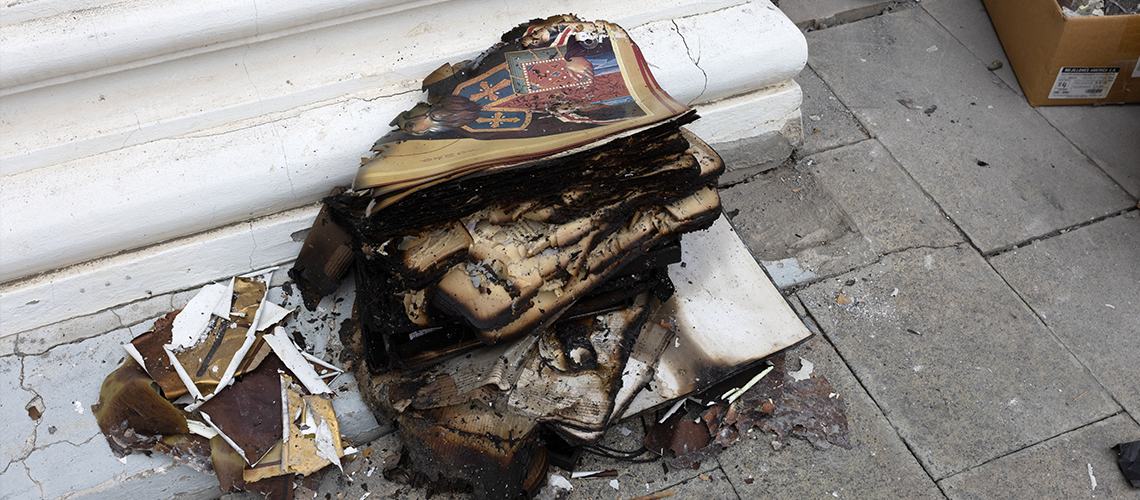

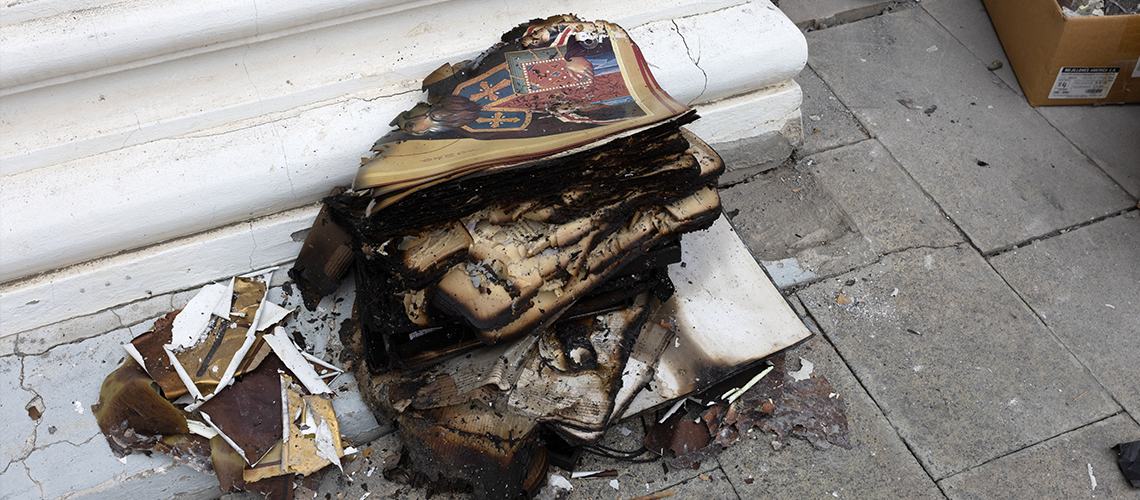

Image caption: Burnt pages of bible left on steps of Orthodox church in Odessa, destroyed by rocket during Ukraine-Russia war. Aleksandr Lesik/AdobeStock.com

In this article, written exclusively for Global Insight, Ukraine’s Prosecutor General describes the destruction and looting of Ukrainian cultural property by Russian troops, and elaborates on the implications for international law.

From the beginning of its invasion of Ukraine, Russia has shown no restraint when it comes to sites of cultural heritage. On 25 February 2022, Russian bombs razed the Ivankiv Historical and Local History Museum, about 50 miles from Kyiv. That day, the world lost 25 paintings of Marija Prymachenko, one of Ukraine’s most famous and most popular artists.

To understand the magnitude of that devastation, one must imagine what it would mean for Germans to lose works of Dürer or Klee; or for Americans to see paintings from Hopper, Pollock or Warhol set ablaze. What would it mean for the French to have bombs obliterate the oeuvre of Matisse, Monet or Renoir? The great Pablo Picasso once exclaimed, after visiting a Prymachenko exhibition in Paris in 1937, ‘I bow down before the artistic miracle of this brilliant Ukrainian’.

The Russian thirst for the destruction of Ukrainian heritage comes as no surprise. It ties in to the campaign of assaulting Ukraine’s national identity; for assaulting the people’s knowledge of their history, origin and culture, is like cutting roots from a tree. This is why the destruction and looting of works of art and cultural heritage as an exercise of power is no less than barbaric, and this is why cultural property enjoys special protection under international law.

Emerging from the horrors and devastations of the Second World War, the 1954 Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict (‘Hague Convention’) became the first international instrument to focus solely on the preservation of cultural property during conflicts. The Hague Convention protects movable or immovable property of great importance to the cultural heritage of every people. This includes monuments of historical or artistic interest and works of art, as well as scientific collections, collections of books and others. The Hague Convention obliges states parties to ‘safeguard’ and to ‘respect’ cultural property. It directs states to prohibit and prevent any form of theft, pillaging or misappropriation of, and any acts of vandalism directed against, cultural property.

The Russian thirst for destruction of Ukrainian heritage comes as no surprise. It ties in to the campaign of assaulting Ukraine’s national identity

Andriy Kostin

Prosecutor General of Ukraine

Likewise, the Geneva Convention’s Additional Protocol I (AP I) contains relevant provisions. Article 53 of AP I prohibits the commission of any hostile acts directed against historical monuments, works of art or places of worship that constitute a peoples’ cultural or spiritual heritage. It also prohibits their use in any military effort or to make them objects of reprisals. This rule does not allow for deviation.

Finally, the prohibition of attacks against property of great importance to the cultural heritage of every people is also a firm tenet of customary international law. When conducting attacks, special care is required to avoid damage to some of the most precious civilian objects. This requirement was already recognised in the 1863 Lieber Code, the basis not only for the Field Manual of the United States Armed Forces, but foundational for international humanitarian law as we know it today.

The only case where these obligations may be waived is in cases of ‘imperative military necessity’. Imperative military necessity may only be invoked when and for as long as the cultural property in question has, by its function, been made into a valid military objective, and there is no feasible alternative to obtain a similar military advantage. There is no doubt that the numerous museums hit by Russian bombs were anything but military objectives. Neither was the Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial, the mass grave of thousands of murdered Jewish people, ironically damaged by the missiles of the very man who claims to be conducting ‘a military operation’ to ‘denazify’ Ukraine. And neither was the Dormition Cathedral in Kharkiv, where artwork and stained glass windows were shattered by a Russian cruise missile, or George's Church in Zavorychi, or the Church of the Nativity of the Theotokos in Viazivka.

The list is painfully long. But Russia treats each rule of international law with utter disregard. As a result of the Russian aggression, by the end of December 2023, 872 objects of cultural heritage were destroyed or damaged in 17 regions of Ukraine.

And the invaders are not content to just destroy Ukraine’s national treasures, they also seek to rob them. In April 2022, over 2,000 exhibits were looted from museums in Mariupol, including original works by Arkhip Kuindzhi and Ivan Aivazovsky. From the Museum of Local Lore and Kuindzhi Art, nearly all pieces have been taken by Russian occupiers. In May 2022, Russian forces looted the largest collections of Scythian artefacts in Ukraine from Melitopol: ornaments of Scythian gold, Hunnic and Sarmatian culture.

From the Berdiansk Art Museum, Russian forces stole paintings by world-famous artists and vast collections of precious metals. In Kherson, before retreating from the city in November 2022, from over 13,000 pieces held at the Kherson Art Museum, the occupiers took about 80 per cent and hauled the loot to Crimea. By the end of 2022, the Russian occupiers had stolen thousands of artefacts from almost 40 Ukrainian museums.

The attacks and the plundering show that this war is not primarily about territory. This war is an attack to extinguish the Ukrainian national identity.

The destruction of cultural heritage incurs individual criminal responsibility as provided in article in 85 of AP I. Notably, the Second Protocol to the 1954 Hague Convention specifies a range of ‘serious violations’ relating to cultural property and imposes duties on states parties to prosecute individuals suspected of criminal culpability for major violations.

The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court classifies serious violation of laws and customs of war as war crimes, among them the intentional directing of attacks against historic monuments, buildings dedicated to religion, or art. In 2021, the Office of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court published a comprehensive Policy on Cultural Heritage.

The destruction and pillaging of national treasures are not only modern-day occurrences, historically, they are a common feature of wars of aggression. Infamously, the Nazis, spearheaded by the greed of Hermann Göring, Chief of the Luftwaffe and a member of Hitler’s inner circle, systematically plundered cultural property from every territory they subdued. They specifically created organisations for the purpose of determining the value of public and private collections. Some were earmarked for Hitler's never realised Führermusem, others became the private property of other high-ranking Nazis or were traded to fund the war machinery.

The widespread Russian looting and destruction of Ukrainian heritage is not an incidental or sporadic violation, but rather part of an organised outrage against the nation’s collective memory. More than that, it is part of a wider, frontal attack on the very existence of the Ukrainian people. While the attacks on Ukrainian cultural property may not constitute genocide in and of itself, they form a piece of the wider whole.

When Russia abducts Ukraine’s children, forcibly deports and re-educates our youth – drags them deep into Russian territory – it targets our nation’s future. The raining of Russian missiles on Ukrainian cities assaults our present, every day. The destruction and plunder of our national treasures target our past. Together they form a campaign for the brutal extinction of the Ukrainian identity, memory and history.