Remaining the dispute resolution epicentre: is Med-Arb in Europe’s future?

Credit: Shutterstock

Matthew Finn

Ankura, London

|

A hybrid of mediation and arbitration known as Med-Arb is a less formal, more expedient alternative dispute resolution (ADR) process which can be more flexible when resolving disputes. Although rare in Europe, it is widely used in Asian jurisdictions. In order to remain at the forefront of international dispute resolution, Europe could consider the benefits of Med-Arb: namely, a swift and cost-effective resolution, avoiding more traditional costly and time-consuming processes such as litigation and arbitration. As we enter a period of economic downturn in Europe due to the Covid-19 pandemic, are hybrids that combine arbitration with mediation a better form of ADR?

|

What is Med-Arb?

There are many hybrids of mediation and arbitral approaches. The ideology behind Med-Arb, specifically, is that the parties use the assistance of a mediator in an attempt to reach a settlement. If the mediation fails, the mediator switches roles and takes on the role of an arbitrator to render a binding arbitral award on the merits of the case. Usually, these hybrids are commenced at the early stages of the dispute by the parties or by the arbitral tribunal, although this is not restrictive and hybrids can be considered at any stage of the arbitration.

Hybrids such as Med-Arb afford the flexibility of choosing from mediation or arbitration according to what best fits the parties’ interests.

There are many different forms of hybrid and they include:

• Med-Arb (single) – the same neutral party is both the mediator and the arbitrator;

• Med-Arb (duo) – two different neutral parties are the mediator and then arbitrator and appointed at different stages;

• Med-Arb-Opt-Out – either party can call for a separate arbitrator after the mediation stage;

• Arb-Med-Arb – initial arbitration proceedings, followed by meditation, and then the continuation of arbitration proceedings if the mediation was unsuccessful (very popular in the People’s Republic of China);

• Arb-Med – initial arbitration proceedings are halted before the decision is made followed by mediation regarding the narrowed issues;

• High-Low arbitration – parties arbitrate based on progress and/or parameters decided during the mediation stage;

• Co-Med-Arb – the separate mediator and the arbitrator are simultaneously provided the same submissions and information. The separately appointed mediator firstly attempts to settle the dispute and the arbitrator only gets called back if the mediation fails to arbitrate;

• Mediation and Last Offer Arbitration (MEDALOA) – known as the ‘baseball arbitration’ method and is a concept used in the US, whereby if the mediation fails, the mediator becomes the arbitrator and decides between a proposed ruling presented by each party.

It gives the prospects of early settlement in the mediation stage and gives finality – and a binding nature – in the later arbitration stage.

|

The advantages and disadvantages of Med-Arb will differ depending on the goals and values of the parties, the jurisdiction, as well as the mediator and arbitrator, and may not be universally suitable:

‘the choice of a dispute resolution mechanism whether mediation, arbitration or litigation within the forum of a certain society is strongly influenced by the peculiarities of tradition, culture, and legal evolution of that society’.1

The advantages and disadvantages explored below are generic and may not apply to every dispute.

What are the perceived advantages of Med-Arb?

Med-Arb is a flexible ADR mechanism as it allows parties to design a dispute resolution process to meet the needs of the dispute and the parties involved. Med-Arb not only allows for the prospect of early settlement in the mediation stage, it also provides finality – of a binding nature – in the later arbitration stage.

The Med-Arb approach can be cost-effective at resolving the dispute as it allows the arbitrator to investigate with the parties a pre-action settlement opportunity and, if successful, can save the parties from incurring the time and costs involved in proceeding to arbitration. There is also no duplication in time and cost in getting the arbitrator and parties to understand the dispute, because the mediation flows into the arbitration.

Furthermore, the mediation settlement agreement should be rendered as an arbitral award which gives the parties certain advantages under the Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards, commonly known as the New York Convention.

It could also be argued that Med-Arb increases the likelihood that parties will participate in good faith during the mediation stage, in knowing that should the mediation fail, the parties will lose control over the outcome of the dispute.

What are the perceived drawbacks and considerations of Med-Arb?

As advantageous as Med-Arb can be, there are some perceived drawbacks. Any mediation is confidential between the parties and the mediator. The parties must consent to the terms of any agreement, which only becomes binding when in writing. The mediator, therefore, is only to assist the parties in an impartial manner and is not there to render any decisions or determine the dispute. The mediation is completely voluntary, and the parties are free to walk away at any point.

Arbitration is a complex legal process and has many similarities to litigation, but one which takes place in a private forum. While both mediation and arbitration are confidential between the parties, the arbitrator will be required to determine how the dispute and the award are legally binding on the parties. Therefore, the content of the arbitral awards are not controlled by the parties.

Although arbitration and mediation are different ADR processes with different purposes, the fundamental difference is who makes the final decision: a neutral party or the parties at dispute themselves. It cannot be ignored that the role of the mediator is inconsistent with that of the arbitrator.

Concerns over candour and confidential information

Prima facie, Med-Arb as a hybrid seems to be trying to fit a square peg in a round hole, and it has raised concerns with critics as to how it can work in practice. This is because mediation requires the parties to be candid with the mediator, which necessitates disclosing sensitive information such as their bottom-line negotiating position. Parties will often share more information in mediation than arbitration under the protection of the mediation being conducted strictly on a ‘without prejudice’ basis and completely confidential. If, however, the mediation fails and goes to arbitration then this can change the parties’ approach to be less open and honest, in fear that the arbitrator could later consider such shared information against them in the arbitral award.

There is also a fear among legal counsel that confidential information gained during mediation may taint the arbitrator’s final decision, where the mediator becomes the arbitrator. While a mediator and arbitrator are both completely independent and impartial, parties are concerned that even the most diligent neutrals could carry over unconscious bias from the mediation into the arbitration, as explored in Gao Haiyan v Keeneye Holdings Limited.2 This is especially concerning when a single neutral party is acting as both the arbitrator and mediator. Proponents of Med-Arb could counter-argue that similar situations often arise in litigation and other ADR processes with no ill effects. For example, a judge might be required to disregard evidence they have heard but have subsequently determined to be inadmissible or decide that it was privileged.

To counter this concern, as part of the opening proceedings in mediation the parties could agree on what evidence the neutral is to consider in arbitration, and that the arbitrator shall not base their decision on any information obtained at the mediation stage.

It gives the prospects of early settlement in the mediation stage and gives finality – and a binding nature – in the later arbitration stage.

|

Med-Arb in Asia

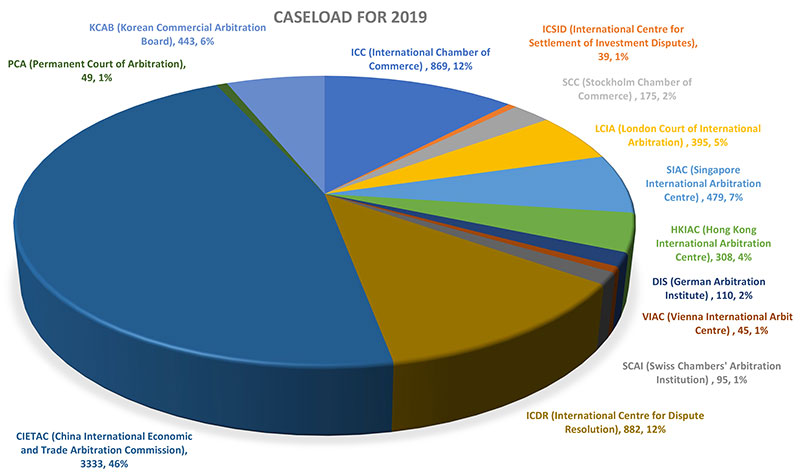

The future of Med-Arb is promising in Asia and is becoming increasingly common. Med-Arb procedures seem popular in China in particular, and in arbitrations that have Chinese involvement. In China, it appears the Med-Arb process involves the mediator evaluating each party’s case and directing them towards settlement, as opposed to mediating and facilitating the parties to a settlement with no evaluation. In an interview in 2011 with the Global Arbitration Review, the Secretary-General of the China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission (CIETAC), quoted that 20 to 30 per cent of CIETAC’s caseload is resolved by Med-Arb each year.3 This is even more impressive considering CIETAC is one of the world’s largest arbitration institutions by the number of arbitrations, with a 2019 market share of 46 per cent among the main international arbitration centres (see Figure 1).4

Figure 1: CIETAC’s 2019 caseload

Unlike the rules in China and Singapore, in Hong Kong, under Med-Arb the mediator has a duty to disclose to all parties any confidential information obtained during the mediation that they consider material to the arbitration.5

In Singapore, the Arb-Med-Arb protocol by the Singapore International Mediation Centre (SIMC) allows for the arbitrator and the mediator to be separately and independently appointed by the Singapore International Arbitration Centre and SIMC.6 It is considered that the arbitrator and mediator will generally be different neutrals; however, the parties may agree that the same neutral may be both the arbitrator and mediator.

Singapore has seen issues in the High Court on Med-Arb such as in Heartronics Corporation v EPI Life Pte Ltd & Ors,7 whereby the defendant refused to cooperate during the mediation stage and the claimant commenced proceedings in litigation. The defendant subsequently applied for a stay of proceedings on the basis of the arbitration clause, but Singapore’s High Court dismissed the stay application as the agreement to arbitrate was discharged by the breach of the mediation agreement. If the parties had opted for an Arb-Med-Arb agreement there would probably have been a very different outcome. It is crucial that parties carefully consider their options should they agree to a Med-Arb or Arb-Med-Arb clause if the agreement should completely fail in the future.

Beyond Asia

Outside of Asia, the Alternative Dispute Resolution Institute of Canada8 launched new Med-Arb rules, Med-Arb designation and accreditation criteria, and Med-Arb templates on 20–22 November 2019. This suggests Canada’s willingness to use Med-Arb more widely.

In another common law jurisdiction, a recent case in Australia (Ku-ring-gai Council v Ichor Constructions Pty Limited9) reviewed Med-Arb under the Australian Commercial Arbitration Act and provided guidance to parties. Despite this case, the use of Med-Arb in Australia remains relatively low. In other common law jurisdictions, Med-Arb does not seem popular with common law lawyers, particularly where arbitral tribunals of common law lawyers are unlikely to offer Med-Arb.

On 12 September 2020, we saw the Singapore Convention on Mediation, formerly the United Nations Convention on International Settlement Agreements Resulting from Mediation, become effective. This works on the same concept as the New York Convention, in that it enables international parties to enforce a settlement agreement arising out of a mediation in the court of any country that is a party to the Convention. As seen with the New York Convention, it provides a direct enforcement of a cross-border settlement agreement between parties resulting from mediation. There are 53 states currently signed up to the Convention, including some of the largest economies in the world such as the US, China, India, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey. The UK and the European Union states appear to be deliberating on whether to sign up to the Convention.

Following the success of the Singapore Convention on Mediation, the UN Commission on International Trade Law is working on draft provisions on expedited arbitration.10 There is also the growing popularity in the UK of construction adjudication over the past 22 years,11 and the international use of FIDIC suite of Standard Forms which introduced dispute adjudication boards commonly referred to as ‘DABs’.12 These recognise that parties’ requirements for the future of international ADR are moving towards swifter and more cost-effective forms, rather than traditional, costly litigation and arbitration. As the Honourable Chief Justice of Singapore Sundaresh Menon recently said, ADR should, instead, stand for ‘appropriate dispute resolution’.13

Conclusion

The growth of Med-Arb internationally, and particularly in Asia, cannot be ignored. In the UK and wider Europe, there appears to be limited use of Med-Arb and so its future in the European disputes market is unknown, with no signs of increased use any time soon.

While the UK and EU remain cynical, hybrids are certain to continue developing and adapting to the needs of the parties in dispute. For Med-Arb to flourish in Europe it will require parties to become more comfortable with such hybrids and mediation, and perhaps see how successful they are in Asia, before accepting whether it can be more widely used in Europe as a form of ADR. It is crucial that London and Paris do not wait too long, otherwise they risk being left behind as the world’s most popular arbitral seats and epicentres of the resolution of international disputes.

Notes

1 Carlos de Vera, ‘Arbitrating Harmony: “Med-Arb” and the Confluence of Culture and Rule of law in the Resolution of International Commercial Disputes in China’ (2003) Columbia Journal of Asian Law.

2 Gao Haiyan v Keeneye Holdings Ltd, Hong Kong Court of Appeal: Tang VP, Fok JA and Sakharani J: CACV No 79 of 2011: 2 December 2011, see www.hklii.hk/eng/hk/cases/hkca/2011/459.html accessed 27 November 2020.

3 ‘An interview with Yu Jianlong’, Global Arbitration Review, 5 September 2011, see https://globalarbitrationreview.com/Article/1030623/an-interview-with-yu-jianlong accessed 27 November 2020.

4 Data taken for 2019 from Global Arbitration News, see https://globalarbitrationnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Caseload-statistics-for-2019.pdf accessed 27 November 2020.

5 Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre – Hong Kong Arbitration Ordinance, section 33(4), see www.hkiac.org/arbitration/why-hong-kong/HK-arbitration-ordinance accessed 27 November 2020.

6 SIAC-SIMC Arb-Med-Arb Protocol, see http://simc.com.sg/v2/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/SIAC-SIMC-AMA-Protocol.pdf accessed 27 November 2020.

7 Heartronics Corporation v EPI Life Pte Ltd &Ors [2017] SGHCR 17, see www.supremecourt.gov.sg/docs/default-source/module-document/judgement/final-gd-hc-192-of-2017-of-17-10-17-pdf accessed 27 November 2020.

8 Alternative Dispute Resolution Institute of Canada website, see http://adric.ca/news/adr-institute-of-canada-launch-new-rules accessed 27 November 2020.

9 Ku-ring-gai Council v Ichor Constructions Pty Ltd[2018] NSWSC 610, see https://ciarb.net.au/resource/case-note-ku-ring-gai-council-v-ichor-constructions-pty-ltd accessed 27 January 2021.

10 72nd Session of the UNCITRAL Working Group II: Arbitration and Conciliation/Dispute Settlement on 21–25 September 2020, see https://uncitral.un.org/en/working_groups/2/arbitration accessed 27 November 2020.

11 Introduction of statutory adjudication under the Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Act 1996, which came into force on 1 May 1998. It is now pt 2 is amended by the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009, pt 8, which came into force on 1 October 2011.

12 Introduced in the 1999 FIDIC suite of Standard Forms (under the red, yellow and silver books) under cl 20 of the 1999 FIDIC Conditions.

13 The Honourable Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon, ‘Shaping The Future of Dispute Resolution & Improving Access to Justice’ (Paper presented at Global Pound Conference Series, Singapore, 17 March 2016) 25.

Back to top