Wuhan's whistleblowers

Sophia Yan, BeijingThursday 9 April 2020

Pic: A woman wearing a face mask walks past a poster of late Li Wenliang, a Chinese ophthalmologist who died of coronavirus at a hospital in Wuhan, March 2020. REUTERS/David W Cerny

Before Covid-19 became a pandemic, the Chinese authorities suppressed information received from experts including whistleblower doctors in Wuhan, the epicentre of the outbreak. The move has proved devastating.

In December, a few patients became mysteriously ill at a hospital in Wuhan, central China. Test results showed a coronavirus infection similar to SARS, an outbreak that originated in China and killed around 800 people in 2002 and 2003.

Dr Ai Fen, Head of Emergency at Wuhan Central Hospital, said she broke out in a cold sweat while reviewing the results, according to a censored interview with Chinese magazine, Ren Wu.

Worried about the implications, Dr Ai informed hospital authorities and sent screenshots to a colleague, purposefully circling the results in red to draw attention to them. She also sent the report to a group of doctors in her department via WeChat, recommending everyone take precautions.

That night, the hospital warned her that people spreading information and causing widespread panic would be held accountable. Later, she was summoned by hospital authorities who instructed her not to discuss this new illness with anyone, including her husband.

‘I was stunned,’ Dr Ai later told Ren Wu. ‘I knew that a very important virus had been found in patients. Other doctors would say, how could you not say anything? This is the instinct of a doctor, isn’t it? What did I do wrong?’

As Dr Ai was being reprimanded, the Chinese government quietly announced it was investigating a novel coronavirus outbreak on 31 December.

A worker in a protective suit is seen at the closed seafood market in Wuhan, Hubei province, China, January 2020. REUTERS/Stringer

Three months later, the coronavirus, which causes a disease known as Covid-19, has spread around the world, infecting more than 1,018,948 people and killing more than 53,211, according to data collected by Johns Hopkins University. Even small corners of the globe, like the Vatican City, have confirmed infections.

The world is in a state of unprecedented upheaval, with heads of state announcing national emergencies, governments using the military to help enforce quarantines, hospitals besieged with patients and health officials struggling to make contingency plans.

Much of that planning is based on data from China – numbers that experts are starting to doubt as the outbreak rips through countries in a terrifying way. Questions are also being asked about how China’s botched response in the first weeks of the outbreak – when authorities silenced many like Dr Ai – has exacerbated the spread of the disease.

A study published by the University of Southampton in March found that if Chinese authorities had instituted disease containment measures just three weeks earlier, 95 per cent of infections could have been prevented.

Business as usual: denial

Government officials hosted annual local meetings in early January, where Zhou Xianwang, Mayor of Wuhan, made no public mention of a health crisis, instead touting his vision of modernising the city’s medical infrastructure. Health officials insisted that less than 50 people were infected.

On 1 January, authorities closed down and sanitised the seafood market believed to be the source of the outbreak, leaving little for scientists seeking clues about the origins of the virus, and how it jumped, most likely, from animals to humans.

Rather than rushing to caution the public in Wuhan, the epicentre of the outbreak, Chinese authorities downplayed the dangers, allowing thousands to gather for Lunar New Year banquets at the end of the month.

Cases continued to mushroom at Dr Ai’s hospital, even after the market was shut. One of her colleagues, ophthalmologist Li Wenliang, fell ill on 10 January after treating a patient who later tested positive for the coronavirus.

These were all early signs that a person who had contracted the novel coronavirus could infect others. Dr Li himself wondered why health officials hadn’t announced the possibility of human-to-human transmission.

Like Dr Ai, he had been previously summoned by local health authorities demanding to know his source of information and whether he ‘realised’ his mistake after he sought to warn medical school classmates in late December about a new virus infection. He had also seen and shared Dr Ai’s early warning.

Within days, police were at his door, accusing him of ‘spreading rumours’. Officers forced him to sign a statement attesting to his ‘illegal activity,’ warning that if such behaviour continued, there would be legal consequences. ‘I never dealt with police before,’ Dr Li later told Caixin, a Chinese media outlet. ‘I was worried that I could not leave without signing the statement, so I just went through the process and signed.’

China finally confirmed human-to-human transmission on 21 January, admitting that patients had infected family members and medical staff.

By then, hospitals in Wuhan had been overwhelmed for weeks and were running out of patient beds. Resident Chen Min, 65, was one of many turned away when seeking medical help for a fever and cough that developed on 6 January. Doctors at three different hospitals in Wuhan repeatedly diagnosed her with a cold and sent her away with basic medicine. Even after a CT scan showed shadows in her lungs and doctors said she needed further treatment, they still sent her home – there wasn’t any space.

Chen Min was in a critical condition by the time she was placed in isolation on 15 January, dying hours later. Because she was never tested for the coronavirus, Chen’s death wasn’t included in the official tally. Doctors told her family it was ‘highly likely’ she died of a coronavirus infection, and pushed for a quick cremation to get rid of her infectious corpse.

‘The patients who died in the emergency department were all undiagnosed and not considered confirmed cases,’ said Dr Ai. ‘Such high human cost at the Wuhan Central Hospital is a direct consequence of the lack of transparency among our medical staff.’

Medical workers inspect the computed tomography scan image of a patient at the Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan, Hubei province, China, February 2020. China Daily via REUTERS.

‘If everyone had been alerted from 1 January, many tragedies could have been avoided,’ she said.

Official death tolls in France, Italy, Spain and the US have all surpassed the 3,300 fatalities reported by Chinese health authorities, prompting countries including the UK and US to express concern that Beijing’s count suppresses the true scale of the outbreak.

Emergency response

Chinese authorities finally locked down Wuhan in late January, cutting travel links and placing the entire city under quarantine. The shutdown expanded to include the rest of the Hubei province; similar measures were later adopted all over the country, limiting the mobility of the population of 1.4 billion people.

Experts, however, said the mass quarantine was too little, too late, as millions had already travelled from Wuhan to other parts of China ahead of a major annual holiday.

If everyone had been alerted from 1 January, many tragedies could have been avoided

Dr Ai Fen

Head of Emergency, Wuhan Central Hospital

Still, rail employees were even banned from wearing face masks – a move aimed at curbing mass panic, even as deaths rapidly ran into the hundreds. For weeks, too, doctors weren’t allowed to wear hazmat suits in Dr Ai’s hospital.

Frustrations hit a peak in early February when Dr Li died from the coronavirus, leading to an unprecedented outpouring of public anger and grief over the government’s handling of the outbreak.

Chinese government censors were in overdrive trying to block trending topics online, including ‘the Wuhan government owes Dr Li Wenliang an apology’ and ‘we want free speech.’

People posted videos of the Les Miserables song, ‘Do You Hear the People Sing?’ while others lamented the irony that China’s constitution guaranteed freedom of speech, which hasn’t been proven in practice.

Such a wave of discontent is extremely rare, especially under strongman Xi Jinping, the leader of the ruling Chinese Communist Party, who has sought to quash dissent for years, cracking down on lawyers, journalists, students, businesspeople. In doing so, he has created an environment that silences people like Dr Ai and Dr Li.

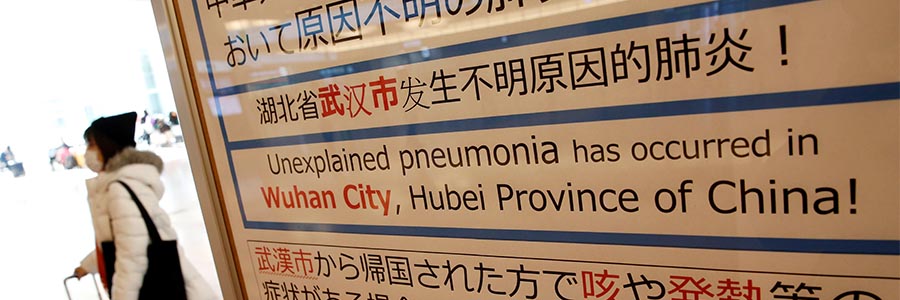

A woman wearing a mask walks past a quarantine notice about the outbreak of coronavirus in Wuhan, China at an arrival hall of Haneda airport in Tokyo, Japan, January 2020. REUTERS/Kim Kyung-Hoon

Dr Li ‘is a tragic reminder of how the Chinese authorities’ preoccupation with maintaining “stability” drives it to suppress vital information about matters of public interest,’ says Nicholas Bequelin, Regional Director for East and South-East Asia and the Pacific at Amnesty International.

China has since axed some local health officials, but nobody more senior has taken responsibility for the response – a fleeting effort to give the impression authorities are being held accountable.

Public anger remains. Videos circulated online of Wuhan show residents chanting ‘fake, fake, everything fake,’ when a top Party official visited recently. But risks loom large for anyone who dares to criticise the government, or even mention the virus.

Dr Li is a tragic reminder of how the Chinese authorities’ preoccupation with maintaining ‘stability’ drives it to suppress vital information about matters of public interest

Nicholas Bequelin

Regional Director for East and South-East Asia and the Pacific, Amnesty International

In late February, China’s Ministry of Public Security announced more than 5,000 cases involving ‘fabricating and deliberately disseminating false and harmful information’ without providing further details.

‘The announcement signalled the government’s determination to further obstruct the flow of information and independent reporting, and critical voices, which are vital for effective responses to a public health emergency of such magnitude,’ said Chinese Human Rights Defenders (CHRD), a network of advocacy groups, in a statement.

CHRD has documented 897 cases of Chinese internet users penalised by police for their online speech or information-sharing about the virus over the past three months, based on publicly available information, indicating that the true scope of the crackdown could be much wider. Punishments have included detentions, enforced disappearances, forced confessions and ‘educational reprimands’, the group said.

Additionally, as of 1 April 2020, Dr Ai Fen has reportedly disappeared.

Infection numbers appear to be subsiding – on some days, China has claimed zero new locally transmitted illnesses. But, again, doubts persist over the numbers, as the government has repeatedly revised its methods for confirming cases. Pictures of thousands of urns outside funeral homes in Hubei province have added to those worries.

Many restrictions remain in place – a hint that the government remains concerned about the health risks, despite declaring victory in what Mr Xi dubbed the ‘people’s war’ against the virus. A number of mobile apps are also now required to indicate an individual’s contagion risk, increasing the government’s digital surveillance capability – a dragnet that is likely to last long after the coronavirus is eradicated.

Sophia Yan is China Correspondent for The Daily Telegraph.