Twenty years of the IBA's Human Rights Institute

With human rights and the rule of law under attack all over the world, the IBAHRI’s work is more important than ever. Global Insight reviews some of the key milestones and most significant achievements since its creation two decades ago under the honorary presidency of Nelson Mandela.

Isobel Souster and Alfonso Redondo

As the last British resident held prisoner in Guantánamo Bay was released in October, lawyers and activists around the world heralded it a triumph for human rights. The detention facilities are emblematic of the gross abuses perpetrated in the fight against terrorism –indefinite detention without trial a clear violation of international law.

Meanwhile, as an unparalleled humanitarian crisis unfolds across Europe with migrants fleeing conflict in Syria, human rights abuses in Eritrea and poverty in Kosovo, leaders throughout the European Union struggle to reach an agreement and are at risk of contravening protocols and their obligations.

In the United Kingdom, the very foundations of human rights are under threat from the government as it plans to repeal the Human Rights Act and distance itself from the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg.

|

The IBAHRI’s objectives are:

-

The promotion, protection and enforcement of human rights under a just rule of law;

-

The promotion and protection of the independence of the judiciary and of the legal profession worldwide;

-

The adoption and implementation of standards and instruments regarding human rights accepted and enacted by the community of nations;

-

The acquisition and dissemination of information concerning issues relating to human rights, judicial independence and the rule of law; and

-

The practical implementation of human rights and the rule of law worldwide, such as through capacity-building initiatives.

|

Human rights appear to be under attack in all parts of the world. Not just in developing and post-conflict countries, but in ‘developed’ countries too. ‘If you look at conflicts around the world and go to the root causes,’ says Hans Corell, former UN Legal Counsel and current Co-Chair of the International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute (IBAHRI), ‘the answer is always the same: no democracy – no rule of law.’ He continues: ‘…the legal profession has a special responsibility when it comes to establishing the rule of law at the national and international levels. And the rule of law is an indispensable element in establishing international peace and security.’

The sentiment is echoed across the IBA. ‘As lawyers, we have a responsibility to help ensure the integrity of our government,’ IBA President David W Rivkin says, ‘and the judiciary, the rule of law, and to prevent human rights atrocities.’

When the legal profession can’t function effectively or independently, human rights violations, impunity and violence follow. This year, as the IBAHRI marks its 20th anniversary, the need to protect and promote human rights across the world remains as pressing as ever.

A turning point for human rights

The Second World War was a turning point in many ways, but particularly so for human rights. Previously, the primacy of state sovereignty meant the rights and wellbeing of citizens, for good and ill, was left in the hands of governments. Speaking at the IBAHRI’s recent 20th anniversary debate, Sir Keir Starmer MP, the former Director of Public Prosecutions for England and Wales, highlighted the changes. ‘The world came together after the shock of Nazi Germany and decided to form international bodies such as the UN, drafted the UN Charter and made a solemn vow that no longer would a state be permitted to do what it liked to its own citizens without having to answer to other states under international relationships,’ he said. ‘States appreciated that Nazi Germany had done to its citizens things that were within the terms of its own laws. A nation-to-nation vow for the future that never again would they allow that to happen without an international mechanism, with states answering to each other, was made.’

The IBA believed that Mr Mandela’s unremitting fight for equality, freedom and democracy stood as a beacon for the values of the Human Rights Institute

Mark Ellis

Executive Director, IBA

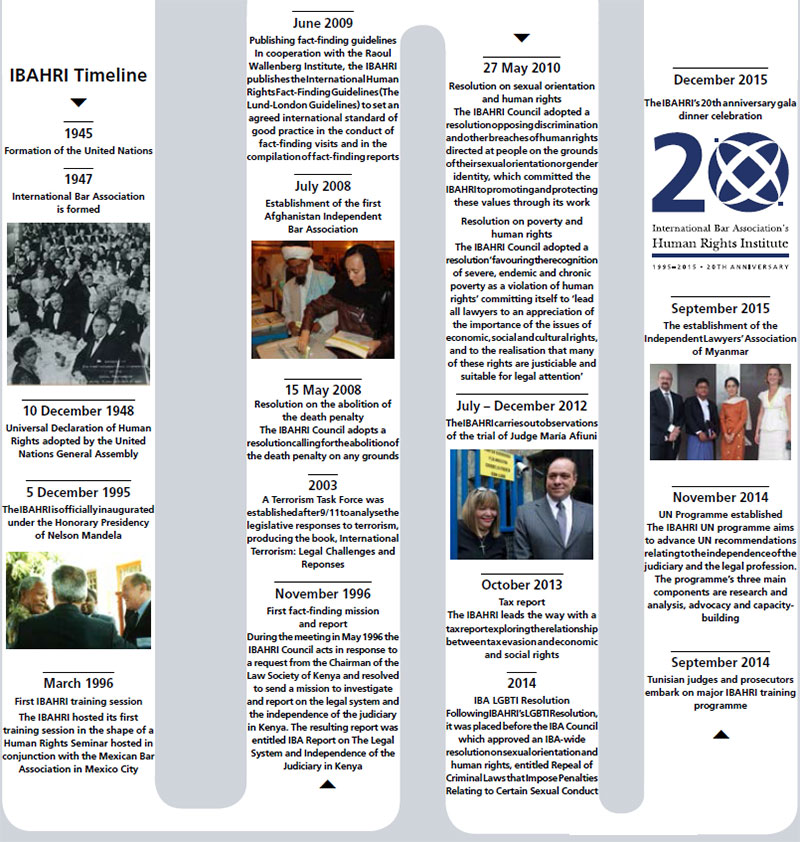

Borne of this newfound internationalism, the International Bar Association was established in 1947, a year before the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the founding document of a whole generation of international human rights treaties that were created in response to the horrors of the Second World War, was drafted. ‘The IBA was formed when it was hoped that the United States, Russia and the British could bring an end to the circumstances that led to the Second World War,’ IBA Honorary Life President George Seward, widely recognised as the IBA’s founding father, said. ‘It was hoped that the lawyers could help with this. So, a world organisation was formed.’

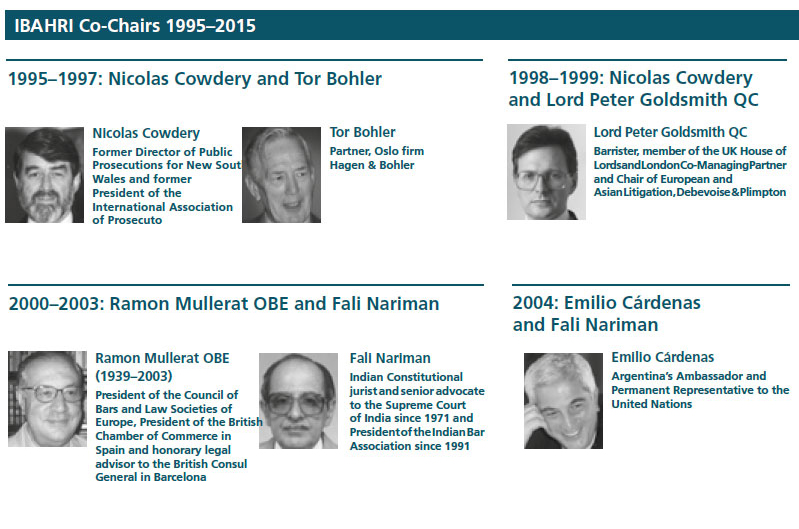

As a fledgling organisation, the IBA was initially only moderately interested in human rights. According to Ambassador Emilio Cárdenas, former Vice-President of the IBA, and Justice Richard Goldstone, former Co-Chair of the IBAHRI and now its Honorary President, its human rights activities were patchy for most of the century. A small number of committees, loosely focused on human rights, came and went, none proving to be particularly successful through protest letters and some observers being sent into the field periodically.

Nevertheless, interest in human rights continued to grow, albeit slowly, thanks to the efforts of a few dedicated and energetic individuals. By the time of the 1994 IBA Annual Conference, concern for human rights had grown considerably. Something happened at that conference that raised awareness of the practical importance of human rights and their relevance, to lawyers as well as citizens. One of the delegates, Modupe Akintola of Nigeria, made comments about Nigeria’s human rights practices, which were reported back to the military government. Upon her return home, she discovered that her passport had been cancelled and for nine months she had to report to the security police on a weekly basis. This initiated a flurry of IBA activity on her behalf. Among the top ranks of the IBA, the enthusiasm to form a body dedicated to human rights was irrefutable.

And so, almost 50 years after the IBA was established, the IBAHRI was officially inaugurated on 5 December 1995 under the honorary presidency of Nelson Mandela. ‘When the IBAHRI was founded,’ says Mark Ellis, IBA Executive Director, ‘Mr Mandela was one year into his term as President of the Republic of South Africa and major progressive social reforms were taking place across the country. The IBA believed that Mr Mandela’s unremitting fight for equality, freedom and democracy stood as a beacon for the values of the Human Rights Institute.’ Mandela agreed to become the firstHonorary President of the IBAHRI, after an IBA-arranged conference of African Bar leaders in South Africa.

Humble beginnings to central role

For the first four years, the IBAHRI had just one member of staff, Fiona Paterson, who was also fulfilling a role as part-time assistant to the then IBA Executive Director. Determined that the IBAHRI play an important part in easing some of the challenges lawyers face, and from 2000 with significant backing from Mark Ellis, Paterson ensured that the IBAHRI began its steady growth to become the sizeable team it is today. She says she felt ‘privileged to meet some extremely brave and inspiring lawyers and judges worldwide’. Over the subsequent two decades, the protection and promotion of human rights moved to the heart of what the IBAHRI stands for.

Since the IBAHRI’s inauguration, it has carried out over 200 projects in 75 jurisdictions across five continents. It has published 65 reports, including the findings and recommendations of fact-finding missions, thematic papers and task force reports. Its international task forces have focused on topics as diverse as sexual orientation, the death penalty, illicit financial flows and terrorism.

As a lawyer working in Zimbabwe, Sternford Moyo appreciates the importance of the IBAHRI’s work, perhaps more than most. Over the last two decades, the IBAHRI has, says the former Co-Chair ‘become an important guarantor of democratic values and a dependable friend of those locked up in daily struggles for the attainment of these important democratic values.’ And it’s been, he adds, ‘a source of support, strength and inspiration for lawyers in Zimbabwe and Southern Africa in general’.

During its early years, trial observations were a core part of the IBAHRI’s work. There are countless examples over the last 20 years when the IBAHRI has been present to oversee trials of lawyers in danger of being victims of miscarriages of justice and improper process.

[The IBAHRI] has become an important guarantor of democratic values and a dependable friend of those locked up in daily struggles for the attainment of these important democratic values

Sternford Moyo

Former Co-Chair, IBAHRI

A recent prominent example involved monitoring the trial of Judge Maria Lourdes Afiuni in Venezuela. In 2009, she was arrested in her courtroom hours after granting bail to a political prisoner, having correctly applied the Venezuelan penal code and a UN Working Group decision that his detention had been unlawful. Placed in the same maximum security prison as individuals she’d sentenced, she has been victim of harassment, abuse and has since claimed she was raped and tortured by prison staff.

The IBAHRI has found her trial to be characterised by multiple human rights violations, and is the only international NGO that has maintained an observation on the case. The former Special Rapporteur on the Independence of Judges and Lawyers, Gabriela Knaul, expressed her concern about the effect such a case could have on the region. ‘I am afraid of the effect of Afiuni’s case on Latin America. Because we cannot accept that a judge could be arrested because of their decision. If there is any kind of allegation that she could have practised some crime it should be previously investigated. It should respect the due process of law.’

In such a hostile environment, the trial observations have proven invaluable. Judge Afiuni’s defence lawyer JoséAmalio Graterol, whose trial was also monitored by the IBAHRI, confirms this. ‘The IBAHRI observations were certainly important to both Judge Afiuni’s case, and to my own,’ he says.‘In my case, my licence to practise was not revoked precisely because there were international legal observers present. This prevented me from being imprisoned and barred from legal practice and for that I am very grateful.’

But the impact of the IBAHRI’s trial observations has reached far beyond Venezuela and Latin America. Julia Onslow-Cole, Head of Global Immigration at PwC Legal, says that she is ‘hugely proud of the work that the IBAHRI has undertaken in monitoring and providing assistance to lawyers on trial around the world… this is pivotal in ensuring freedom from human rights abuses for all.’ She continues: ‘the work is critical – the IBAHRI speaks out for those without a voice and those failed, often by their governments.’

Not only working on behalf of individuals, the IBAHRI also tackles the biggest issues threatening the rule of law on a global scale. The events of 9/11 set governments and international law-making bodies a number of complex and novel legal challenges in terms of responding to global terrorism while protecting people’s fundamental rights and freedoms. At the annual conference in Mexico in 2001, the IBA’s leadership supported the request to create a Task Force on International Terrorism (the ‘Task Force’).

Comprising renowned jurists and initially co-chaired by Justice Richard Goldstone and Ambassador Emilio Cardenas, the Task Force produced two book-length reports. The first, in 2003, was entitled InternationalTerrorism: Legal Challenges and Responses and focused on key areas including: civil liberties and human rights; the use of force as a response to terrorism; preventing the financing of terrorism and international cooperation in criminal justice; and the role of the ICC. The second,Terrorism and International Law: Accountability, Remedies and Reform,was published in 2011 and provides a global overview of counter-terrorism, including but not restricted to the US-led ‘war on terror’, by considering case law and examples of state practice from all continents. Other isses addressed include: the framework of international conventions against terrorism; international humanitarian law; international human rights law; the investigation and prosecution of terrorist crimes and of international crimes committed in the course of counter-terrorism; reform in counter-terrorism; and victims’ right to a remedy and reparations.

Juan Méndez, UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, was Co-Chair of the IBAHRI in 2010 and 2011 and was a member of the Task Force that produced the 2011 report. Asked what he would regard as the IBAHRI’s greatest successes over the last 20 years, Méndez says he is ‘particularly proud of the report on Human Rights and Terrorism produced by the Task Force’.

Rule of law in Afghanistan

Protecting the independence of the legal profession and the rights of lawyers is at the forefront of the IBAHRI’s mandate. This is achieved in part by the Institute’s capacity-building work – creating sustainable and effective organisations for the promotion of the rule of law. A prime example is the Afghanistan Independent Bar Association (AIBA), the country’s first, which was established on 30 July 2008 at a General Assembly in Kabul. It was only four years earlier than the HRI commenced work in the country. When the project started, there were only 100 registered lawyers in Afghanistan, and there wasn’t even an accurate translation of ‘bar association’ in Dari. Now, since the conclusion of the project, there are over 2,500 registered lawyers and a functioning national bar association.

Rohullah Qarizada, the President of the AIBA, acknowledges the ‘very important and vital role’ that the IBAHRI played in the establishment of the Association. Not only did the IBAHRI work to establish the AIBA, but also to ensure that it was an organisation that was inclusive and for the benefit of all Afghani citizens and legal professionals.

As a result, the AIBA is one of the only bar associations in the world to have a quota for women on all executive committees and compulsory pro bono requirements for members. In the process of setting it up, consensus was reached that there should be adequate representation; therefore the bylaws expressly state that of the two

Vice-Presidents at least one must be a woman, and all lawyers undertake three cases pro bono each year.

Human rights: East v West

There has been a tendency to speak of social, cultural and economic rights as if they are fundamentally distinct from civil and political rights. While there is no distinction drawn between rights in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the distinction arose in the Cold War tensions between East and West. According to the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, ‘market economies of the West tended to put greater emphasis on civil and political rights, while the centrally planned economies of the Eastern bloc highlighted the importance of economic, social and cultural rights’. This dichotomy has been reflected in the work of the IBAHRI, as Moyo notes. ‘We have traditionally looked at human rights violations as violations by governments. We have looked mainly at political rights.’

A significant shift occurred in 2012, when the IBAHRI convened a task force on illicit financial flows, poverty and human rights. Its remit was to analyse how illicit financial flows, specifically the proceeds of tax evasion, impact poverty and subsequently affect the enforcement of socio-economic and cultural rights. The task force’s report, Tax Abuses, Poverty and Human Rights, aims to initiate public discussion among relevant stakeholders on the key issues relating to tax abuses, poverty and human rights. According to Moyo, ‘the work of the task force looks at a wider range of rights, including socioeconomic rights and looks at possible corruption of corporates.’ The task force was chaired by Thomas Pogge, Professor of Philosophy and International Affairs at Yale University in the US. Acknowledging the vital work of the task force, he said that ‘the great merit of this task force is that it comes forward with a lot of expertise.’

This work exemplifies the vital link between business and human rights. In an interview with the IBA Corporate Social Responsibility Committee, Professor John Ruggie, UN Special Representative for Business and Human Rights, stressed the importance of the ‘Protect, Respect, Remedy’ framework. He acknowledged ‘that is the most difficult context for business in human rights. The worst abuses occur in conflict-affected areas. Many companies tend to treat them as law-free zones even though there are laws on the books – but no one is enforcing them.’

In an interview at the 2015 IBA Annual Conference in Vienna, Kofi Annan, former Secretary-General of the United Nations, emphasised the effect that the legal profession can have. ‘Lawyers have a very important role to play,’ he says. ‘All of you are men and women of influence in your societies… You can influence your clients… You can tell them what is right, they might resist it, but try and try again.’

That business and human rights cannot and should not be separated, a principle that has only been recognised within the last decade, is exemplified by the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. According to Nicholas Cowdery, the inaugural Co-Chair of the IBAHRI from its creation in 1995 to 2000, one of the challenges faced by the IBAHRI is to continue to persuade business lawyer members of the IBA that human rights protection is not some ‘warm and fuzzy’ add-on to the IBA’s work. ‘Without human rights observance in the jurisdictions in which they practise, they would be out of work. They have a stake, as much as practitioners in any other field, in actively supporting the work of the HRI, more than ever in this 800th anniversary year of the Magna Carta.’ The anniversary of the Great Charter, the document that introduced the notion of lawful process and limitations on government power crystallises the work we must all embark upon to protect human rights.

Aiding the Arab Spring

Capacity-building has come to form a central part of the work of the IBAHRI. Through educating the judiciary, lawyers, prosecutors and other legal practitioners about the rule of law and their role in its protection and promotion, impunity for human rights abuses can be greatly reduced. Judges have been trained around the world, in Tunisia, China, Brazil and Hungary, among others. According to Hans Corell, the training in Tunisia has been a particularly ‘great success’. As the country comes out of an authoritarian system, judges do not know how to work in a democracy. The IBAHRI training programme aims to train all Tunisian judges in human rights.

‘We’ve been doing wonderful work in Tunisia, wonderful training there, many judges have gone through a training programme,’ says IBAHRI Co-Chair, Helena Kennedy. ‘You’ve got to remember that when people have been judges in systems that were authoritarian, the idea of a judge making a decision that might be critical of the government just couldn’t happen. So these judges have been hungry to learn, “how can you be a judge in a democracy?” It’s been such a great success for the Human Rights Institute, but it’s what the IBA can do, that often other organisations can’t.’ Almost all judges in the country, around 1,800, have participated in training.

A major strength of the IBAHRI is its reach to all corners of the world. Latin America has been a focus of the IBAHRI’s efforts for several years. Working with key Mexican and Brazilian justice institutions and UN expert bodies, the IBAHRI has implemented nationwide torture prevention courses for judges, prosecutors, public defenders and produced core training materials. Strengthening the legal profession through capacity-building is a crucial success of the IBAHRI.

Myanmar: the road to reform

More recently, the IBAHRI supported the establishment of the first independent national professional organisation of lawyers in Myanmar. As the country began to open its doors to the world and the military regime loosened its grip, the IBAHRI carried out a fact-finding mission in Myanmar in 2012. The report that followed, The Rule of Law in Myanmar: Challenges and Prospects, contained recommendations relating to the establishment of a national bar association.

There had previously been some regional bar associations, but all were deemed illegal by the military government. As the regime began to relax some of its oppressive laws, the IBAHRI saw the opportunity to begin working with stakeholders on the ground, amongst them Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, and members of the legal profession to reach a consensus for a national bar to be established. In meetings held with various parties during 2014, the IBAHRI has heard consensus across the profession, the judiciary and government that the body responsible for regulating and disciplining the legal profession should be more independent to enable the rule of law to be effective in Myanmar.

Myanmar gained prominence on the international news agenda as its first free and fair elections in 25 years were held in mid-November, and Aung San Suu Kyi remained a worldwide symbol of freedom and democracy. Suu Kyi spent 15 years under house arrest and since her release in 2010, she has gone from dissident to politician spearheading the drive for legal and political reform in Myanmar as leader of opposition party, the National League for Democracy, and Chairperson of the Committee for the Rule of Law and Tranquillity. Working with the IBAHRI with the aim of promoting discussion on the need to reform current rules governing Myanmar’s legal profession, she hosted an IBAHRI workshop in October 2014. 250 lawyers and civil society representatives have taken part in IBAHRI workshops held in every state and region across Myanmar. Participants learned about the key democratic elements of the election cycle and applied this knowledge to plan elections for the Independent Lawyers’ Association of Myanmar’s federally composed governing body.

In a recent interview with the IBA, Aung San Suu Kyi asked ‘how can you separate human rights from rule of law and how can you separate human rights from politics?’ A film created by the IBAHRI, Myanmar: the long road to reform, charts the country’s transition from regime to democracy. ‘Through building bar associations in places like Afghanistan and Myanmar,’ David W Rivkin says, ‘we have created new civil society institutions that can serve as a meaningful check on government power.’

United Nations

Lawyers are at the forefront of the fight to protect human rights. Without an independent legal profession, victims of human rights violations would not be able to exercise their right to redress. The effective implementation of UN recommendations relating to the independence of the judiciary and legal profession is therefore at the heart of the promotion and protection of human rights. With this in mind, the IBAHRI has launched a United Nations Programme, focused on UN recommendations relating to the independence of the judiciary and the legal profession. The programme comprises three complementary components:

• Advocacy: to advocate for the independence of the judiciary and legal profession, focusing on UN human rights mechanisms in Geneva;

• Capacity building: to train lawyers, judges and bar associations to engage with UN human rights mechanisms on issues related to their professional independence; and

• Research and analysis: to inform state policies on, and implementation of, UN recommendations relating to the independence of the judiciary and legal profession.

Lawyers, judges and bar associations have a vital role to play in ensuring their professional independence, and UN human rights mechanisms provide effective and accessible tools to promote relevant policies and their implementation on the ground.

Continuing challenges

The major successes of the IBAHRI over the last two decades are innumerable. Challenges, of course, remain. ‘It is a small team and the world is very big!’ says the IBAHRI Principal Programme Lawyer, Alex Wilks. ‘It is important that the IBAHRI stays flexible and able to react quickly while maintaining strategic focus’. Funding is one of the key challenges facing the IBAHRI. Projects are funded by the generous support of its members and funding bodies, including International Legal Assistance Consortium (ILAC).

As part of the biggest representative organisation of lawyers in the world, the IBAHRI has come to be a unique voice in the human rights field. According to Nicholas Cowdery, ‘the IBAHRI will always have a role in the international legal profession. There are broad and narrow human rights issues arising constantly in the ways in which both civil and criminal laws are made, applied and enforced at local and international levels.’ The future of the IBAHRI rests on the dedicated work of lawyers, offering their services pro bono and being able to secure crucial funding. An independent and effective legal profession plays a fundamental role in facilitating access to justice, ensuring accountability of the state and upholding the rule of law.

The IBAHRI can step into areas other NGOs can’t because it has that great weight and heft that comes with belonging to an organisation that brings together such incredible lawyering

Helena Kennedy

Co-Chair, IBAHRI

Phillip Tahmindjis is the Director of the IBAHRI. He is as aware as anyone of the ongoing challenges facing the IBAHRI, notably ensuring it remains properly funded. And, of course, security’s a major issue, given the dangerous places that have received on-the-ground assistance from the IBAHRI over the years – Syria and Afghanistan, to name just two recent examples. Nevertheless, he’s also able to enumerate with pride some of the major successes: establishing the Afghan Bar Association, in which he was extremely involved; training all the judges in Tunisia in human rights; the poverty task force whose report showed the link between illicit financial flows, poverty and human rights; and the work in Geneva with the Universal Periodic Review. He hints at one of the ways the IBAHRI is able to achieve so much. ‘As the IBAHRI works through the members of the legal profession, we leverage the IBA’s networks to deliver human rights and also to support the profession itself which is under attack in many countries,’ he says.

Indeed, for Helena Kennedy the IBAHRI is a unique organisation with powers beyond that of a non-governmental organisation. ‘The reason why the IBAHRI can step into areas that perhaps other NGOs and other organisations can’t is because it has that great weight and heft that comes with belonging to an organisation that brings together such incredible lawyering and judging from around the world,’ she says. ‘That gives it convening power, it gives it influence, it gives it prestige, it means that lawyers and judges are prepared to engage with us.’