Ukraine’s stolen generation

Andriy Kostin, Prosecutor General of UkraineWednesday 24 May 2023

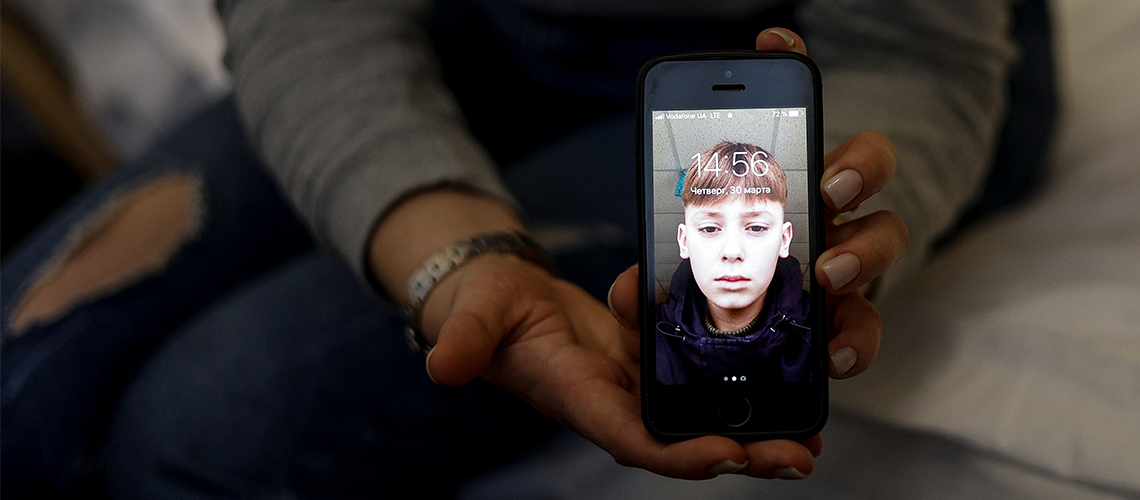

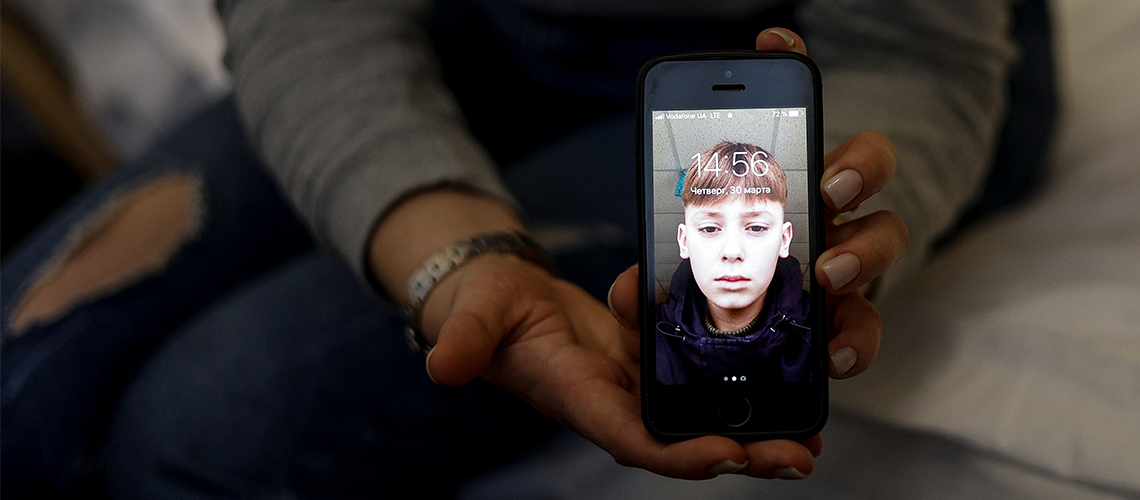

Alla Yatsentiuk shows a picture of her 14-year-old son Danylo, who went to a Russian-organised summer camp from non-government controlled territories and was then taken to Russia, as she speaks with Reuters before travelling to take Danylo back, at a volunteer centre in Kyiv, Ukraine March 30, 2023. REUTERS/Valentyn Ogirenko.

In this article, written exclusively for Global Insight, Ukraine’s Prosecutor General explains how Russia’s systematic abduction and deportation of Ukrainian children violates international law.

On 17 March 2023, the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued arrest warrants for Russia’s President Vladimir Putin and Maria Lvova-Belova, Russia’s Commissioner for Children's Rights, alleging responsibility for the war crime of deportation of Ukrainian children from occupied areas of Ukraine to Russia.

Throughout its eight years of aggression against Ukraine, Russia has been relentlessly pursuing the eradication of Ukrainian identity among children residing in the occupied territories. Deportation, separation from their families, transfer to Russian households, imposition of citizenship, Russification and militarisation have been used to forcefully transform children into enemies of their own nation.

International law defines a ‘child’ as any person who has not yet turned 18. The abduction and deportation of children is considered one of the six grave violations against children during armed conflict and is prohibited by international human rights law, international humanitarian law and international criminal law. It is one of the five prohibited acts under the Genocide Convention of 1948.

In 2014, after Russia annexed the Crimean Peninsula, more than 80 children from Luhansk were halted or captured at checkpoints and deported. After Ukraine sued, the European Court of Human Rights found the children were taken into Russia ‘without medical support or the necessary paperwork’. Ultimately, the children were returned to Ukraine before a final decision was made. Approximately 30 Ukrainian children from Crimea were adopted by Russians under a programme called the Train of Hope. It is likely that some of these children were recruited to serve as Russian soldiers. Since 2015, the Young Army Cadets National Movement has trained young people in Crimea and Russia for eventual recruitment into the military.

Estimating the precise number of Ukrainian children who have been abducted by Russia is a challenging task. According to a report from the Humanitarian Research Lab (HRL) at Yale School of Public Health, since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, over 6,000 Ukrainian children aged between four months and 17 years old have been detained at various camps and similar facilities in Russia. According to the data collection system Children of War, maintained by the Ukrainian government, 19,394 children have been deported to Russia, of whom 11,134 have been located and 360 have been returned.

Abducted Ukrainian children have been forcefully dragged across the entire Russian territory. The Russian child abduction machinery spans from annexed Crimea to Russia’s eastern coast. The HRL has identified 43 facilities handling those children, scattered across Russia, including one camp in Siberia and one as far east as Magadan Oblast near the Pacific Ocean – 3,900 miles from the Ukrainian border.

The primary purpose of these camps is ‘Russification’ through systematic re-education, including force-feeding children with Russian propaganda, cultural, patriotic and/or military education. Multiple camps are advertised as ‘integration programmes’, aiming to uproot Ukraine's younger generation and transplant them into the Russian government's vision of national culture, history and society. Some of the children are placed with families in Russia through a fast-track adoption programme. The system of abduction and re-education is deeply entrenched at all levels of the Russian government. It is centrally coordinated, with dozens of federal, regional and local figures directly engaged in operating and politically justifying the programme. The alleged ‘consent’ from the children’s parents – including sometimes signing over power of attorney – is either obtained under duress, through deception or not at all.

By targeting and stealing the next generation of Ukrainians, Russia is manifestly demonstrating a brutal extinction policy against the Ukrainian people

Andriy Kostin

Prosecutor General of Ukraine

Russia, being a State Party to the 1989 UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), has a binding obligation to respect and ensure the full range of civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights of all children under its control. There is no derogation from this – neither during public emergencies nor armed conflict. The Committee on the Rights of the Child, the body surveying States parties’ adherence to the CRC, has already called for Russia to uphold its duty to protect children from physical and psychological violence.

The CRC stipulates that children have the right to a name and nationality, as well as the right to be cared for and to know their parents. States parties must respect a child's right to maintain their identity, including their nationality and family relations. They may not separate them from their parents against their will, except through due process and where it serves the child's best interests. Furthermore, no child should be subjected to arbitrary or unlawful interference with their privacy, family or home.

The Russian government's programme of arbitrarily separating Ukrainian children from their parents and caregivers, deporting them and imposing Russian citizenship upon them is a manifest violation of these rights. The system’s very purpose is to eliminate those children’s identity, sever family relations and absorb them into the Russian nationality.

The CRC prohibits adoption in the absence of an evaluation regarding the child’s status concerning parents, relatives and legal guardians. Intercountry adoption is to be considered an instrument of last resort, and the Ukrainian government has issued a general suspension of the practice. Normally, Russian law prohibits the adoption of foreign children without the consent of the home country. However, in May 2022, just months after the invasion, Putin conveniently signed a decree making it easier for Russians to adopt and naturalise Ukrainian children without parental care – and more difficult for relatives to bring them back. Russia has even prepared a register of ‘suitable’ Russian families for Ukrainian children – the government grants payment for each child who obtains citizenship and even operates a hotline to pair Russian families with children from the Donbas.

The UN Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children stipulate that in emergency situations children are not to be moved to a country other than their habitual residence except for compelling reasons, including health, medical or safety. If a move is absolutely necessary, they should stay as close as possible to their home, be accompanied by a parent or caregiver, and there must be a clear plan for their return. UNICEF and Save the Children have called for a moratorium on the practice concerning children uprooted by the war in Ukraine. They emphasised that in conflict situations children are at high risk of exploitation, abuse and trafficking and that unaccompanied children may not be presumed to be orphans.

Evidently, none of these standards are being followed by Russia. The expedited adoption of captured Ukrainian children by Russian families, let alone their deportation to re-education camps or anonymous foster care, is a blatant violation of the CRC's fundamental obligations and internationally recognised standards and guidelines.

Alongside human rights considerations, children are specially protected by the laws of war. International humanitarian law recognises children as a particularly vulnerable group in times of conflict. Under the 1949 Geneva Conventions, children, as members of the civilian population, are recognised as ‘protected persons’ when in the hands of the occupying power of which they are not nationals. Attacks against them are forbidden and they are to be treated humanely, with respect for their lives and physical and moral integrity.

The Fourth Geneva Convention (‘GCIV’) provides specific provisions for the treatment of children who have been separated from their families during war, including those who have been evacuated from their homes due to fighting. Family members must be able to communicate with one another, systems must be established to identify and register separated children, and the temporary evacuation of children should always be to a neutral state with parental consent. The Convention only permits the total or partial evacuation of the civilian population from a certain area under very specific and restrictive conditions, including where required for the security of the population or for imperative military reasons. Such an evacuation may only be temporary, and the population must be allowed to return as soon as possible. The occupying power can only evacuate individuals to another area within the bounds of the occupied territory – it must inform the protecting power responsible for this population of any transfer and evacuation as soon as it has taken place and must ensure that family members are not separated from each other. The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe’s Moscow Mechanism's latest report –issued on 28 April 2023 – confirmed that non-consensual evacuations, transfers and prolonged displacement of Ukrainian children constitute violations of international humanitarian law, and in certain cases amount to grave breaches of the GCIV and war crimes, notably violation of the prohibition on forcible transfer or deportation under Article 49 of the GCIV.

Again, none of this is adhered to by Russia. Families are being ripped apart, parents are generally unable to contact their children or know of their whereabouts, let alone any prospect of their return. Russia, as the initiator of the war of aggression against Ukraine, is anything but a neutral state. One cannot respect a child’s ‘moral integrity’ while forcing them through brainwashing exercises, as Putin and his henchmen have done.

Concerning individual criminal accountability, the Rome Statute of the ICC defines deportation as a war crime. It prohibits the ‘unlawful deportation or transfer’ (Article 8(2)(a)(vii)), which includes the deportation or transfer of one or more persons to another state or to another location. It also, more specifically, penalises the deportation or transfer of all or parts of the population of an occupied territory within or outside this territory (Article 8(2)(b)(viii)). Evidently, the Chief Prosecutor of the ICC is convinced there are reasonable grounds to believe that Putin and Lvova-Belova bear criminal responsibility for these crimes, albeit through different actions (or inactions), either directly, jointly with others and/or through others. It remains to be noted that such deportation of a population does not only constitute a war crime under the ICC’s statute. It is widely considered to be a crime under customary international law, being criminalised in a wide range of international conventions, beginning with the Nuremberg Charter of 1945.

In March 2023, the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Ukraine determined that Russia’s transfer and deportation of children are war crimes. It found that:

‘in none of the [examined] situations, transfers of children appear to have satisfied the requirements set forth by international humanitarian law. The transfers were not justified by safety or medical reasons. There seems to be no indication that it was impossible to allow the children to relocate to territory under Ukrainian Government control. It also does not appear that Russian authorities sought to establish contact with the children’s relatives or with Ukrainian authorities.’

Finally, by targeting and stealing the next generation of Ukrainians, Russia is manifestly demonstrating a brutal extinction policy against the Ukrainian people. The meaning of genocide and the acts that fall under it are defined in the Genocide Convention of 1948 and in Article 6 of the Rome Statute. There, genocide is defined as an act committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, any national, ethnic, racial or religious group. These actions include killing members of the group, causing them serious bodily or mental harm, deliberately inflicting conditions of life calculated to bring about the group’s physical destruction in whole or in part or imposing measures intended to prevent births. It also includes forcibly transferring children of one national group to another (Article 2(e) of the Genocide Convention). Russia seeks to destroy Ukrainians as a group – make them extinct not only through killing and acts of violence but through the transfer of Ukrainian children to Russia and placing them with Russian families, thereby cutting them off from their own community, erasing their identity as Ukrainians.

Indeed, the ordeal of the stolen Ukrainian children does not end with their physical placement on the territory of Russia. It continues through their integration and absorption into the national group of the Russian people. This is evidenced by Russia’s acts around the special procedure for obtaining guardianship over Ukrainian minors and the accelerated procedure for granting them Russian citizenship. These measures enable a legal bond between the displaced children and the new (Russian) national group. At the same time, cultural, linguistic and educational integration takes place. Children live in Russian families, get Russian education and everything is done for them to consider themselves Russians. All of this is accompanied by public propaganda of such actions, designating the process as deliberate conduct with the specific intent to destroy the Ukrainian nation.

For Ukraine – and for the rest of the world – the ICC warrants are a crucial milestone on the path towards accountability for core crimes and a seismic event on both legal and political planes. The ICC’s decision sends a forceful message: it glaringly denounces to the world the disgrace, the repulsiveness and the atrocity of these heinous crimes which turn children into spoils of war.