The ‘guardrails of the law’ let down

William Roberts, IBA US CorrespondentWednesday 24 July 2024

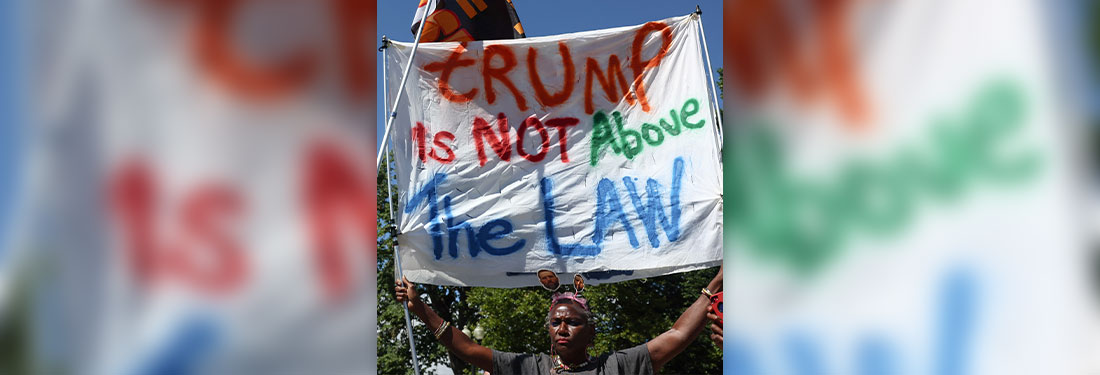

Activist Nadine Seiler holds a banner outside the US Supreme Court, following Donald Trump's bid for immunity from federal prosecution. REUTERS/Leah Millis

In a surprising judgment, the US Supreme Court has given former President Donald Trump broad immunity from criminal prosecution. Global Insight assesses the implications.

In 1787, when America’s founders debated the US Constitution, they endeavoured to properly define the role and powers of the new head of state. Three years after the Revolutionary War with Great Britain, one thing was clear: they didn’t want a king.

The founders settled on a president whose powers would be balanced by a legislature and an independent judiciary. Importantly, the president could be subject to checks, including impeachment by Congress. And, the Constitution says, the president ‘shall nevertheless be liable and subject to Indictment, Trial, Judgment and Punishment, according to Law’.

Now, in a surprising judgment, the US Supreme Court has given former US President Donald Trump broad immunity from criminal prosecution – something no previous president has enjoyed. Trump and his supporters cheered the ruling, which has given momentum to his campaign for re-election in November. But the judgment has been widely criticised and has added fuel to calls for institutional reforms of a Supreme Court that’s declining in public approval.

Congress ‘may not criminalize the President’s actions within his exclusive constitutional power’, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in the majority six–three opinion. ‘Neither may the courts adjudicate a criminal prosecution that examines such presidential actions. We thus conclude that the President is absolutely immune from criminal prosecution for the conduct within his exclusive sphere of constitutional authority’.

The opinion draws a series of concentric circles of immunity defence around a president that sharply limits the application of criminal law

The opinion draws a series of concentric circles of immunity defence around a president, that sharply limits the application of criminal law. It effectively means two federal criminal cases pending against Trump won’t go to trial until after November’s election, if at all.

Reaction among constitutional scholars across the US has been almost uniformly scathing. The judgment has the ‘practical effect’ of granting Trump ‘complete immunity by delay’, wrote Laurence Tribe, Carl M Loeb University Professor of Constitutional Law Emeritus at Harvard Law School.

Jed Shugerman, a professor of law at Boston University School of Law, calls the opinion a ‘historical, constitutional embarrassment’ and ‘incoherent’. The Court’s majority showed a ‘disregard for constitutional methods and the court’s legitimacy’, Shugerman says.

The justices ‘contorted logic’ and dealt ‘enduring damage’ to the Constitution, writes Aziz Z Huq, Frank and Bernice J Greenberg Professor of Law at the University of Chicago. Thomas Wolf, Director of Democracy Initiatives and a constitutional lawyer at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University Law School, calls it a ‘shocking and lawless opinion’.

The six justices forming the Supreme Court’s majority in the case rooted their opinion on an overriding concern that the president must be free to act boldly and with vigour in executing the functions of their office. Even conduct within ‘the outer perimeter’ of official action is presumptively immune, the majority ruled. And, while private conduct isn’t immune, it can’t be prosecuted with reference to any official conduct or inquiry into presidential motives.

From the Capitol to the Court

The case arose out of the US Department of Justice’s charges against Trump for his alleged role in the 6 January 2021 attack by his supporters on the US Capitol. After Trump falsely claimed the election was stolen, an angry mob invaded the Capitol building where Congress was meeting to ratify Joe Biden’s election win. More than 100 police officers were injured, some severely – an officer died the next day. One protestor was shot by Capitol Police, and three others died in the mayhem for health reasons. Then Vice President Mike Pence and senior congressional leaders were threatened as Trump and his allies tried to push Congress to accept fraudulent slates of electors, according to testimony presented to the January 6 Committee of the US House of Representatives in summer 2022.

The National Guard was called out and order restored, but the nation was shocked. The opposition-controlled House of Representatives impeached Trump for ‘incitement of insurrection’. Most Republicans in the Senate, however, refused to convict.

Congress, newly seated in early 2021, then held hearings, and the House of Representatives’ January 6 Committee conducted an 18-month investigation of Trump’s role in the events at the US Capitol. In an 800-page report, the Committee found Trump had orchestrated a fraudulent campaign to stay in power and fomented the violence.

In 2022, the House issued criminal referrals of Trump and others to Attorney General Merrick Garland, who appointed Special Counsel Jack Smith, previously a war crimes prosecutor in The Hague, to investigate. In August 2023, a federal grand jury in Washington indicted Trump on four counts of conspiracy to defraud the US – charges he denies. The case is the first criminal prosecution of a former president for actions taken during his presidency.

Hypothetically now, under the new standard of immunity, a president wouldn’t be prosecuted for ordering the US Navy’s elite commandos to kill a political rival

In federal court in Washington, DC, Trump’s lawyers moved for dismissal, arguing presidents have absolute immunity from criminal prosecution. The trial judge and an appeals court rejected his claims.

Now, the Supreme Court’s ruling throws the Special Counsel’s prosecution of Trump into risk of collapse. It remands the case back to trial court, which must now parse through the pending indictment and underlying evidence to remove any reference to official conduct.

Off limits are Trump’s conversations with Justice Department officials about convincing states to substitute Biden’s electors with fraudulent Trump slates. Trump’s pressure on then Vice President Mike Pence to use his position in the Electoral College to allow fraudulent electors to be counted ‘is at least presumptively immune from prosecution’, Chief Justice Roberts opines. Trump’s speech to the mob and his tweets rallying his supporters are also ‘likely to fall comfortably within the outer perimeter of his official responsibilities’. The prosecution further cannot inquire into the former president’s motives. The remaining allegations must involve unofficial acts without any reference to official conduct.

Interestingly, Justice Amy Coney Barrett dissented from this last part of the Supreme Court’s ruling, arguing it goes too far and creating a five–four split in the opinion. ‘The Constitution does not require blinding juries to the circumstances surrounding conduct for which Presidents can [be] held liable’, Barrett wrote.

Barrett’s position may be where the eventual centre of the Court lies. Roberts added a footnote to the majority opinion that nods in her direction, suggesting public information about official conduct is admissible evidence. The exchange appears to give prosecutors an opening to preserve the case against Trump.

Meanwhile, for ancillary reasons having to do with questions about the Special Counsel’s authority raised in the immunity judgment, the charges in the Mar-a-Lago classified documents case – relating to, among other things, allegations that Trump mishandled confidential government documents he took when he left the White House in 2021, which he denies – have been dismissed. The prosecution has appealed.

The immunity ruling also affects the two state criminal cases pending against Trump. Sentencing in Trump’s hush money trial in New York, previously scheduled for 11 July, has been delayed until September as the Court reassesses the admissibility of bombshell testimony by a White House aide. A racketeering trial in Georgia involving election fraud charges against Trump and 15 others – already mired in pre-trial motions – will be further complicated by the need to separate Trump from other defendants. Trump and his 15 co-defendants have pleaded not guilty.

The dissenting judges on the Supreme Court put forward a pair of blistering deconstructions of the majority’s reasoning. ‘The relationship between the President and the people he serves has shifted irrevocably’, wrote Justice Sonia Sotomayor, joined by Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson. ‘In every use of official power, the President is now a king above the law’, Sotomayor added. ‘With fear for our democracy, I dissent.’

In a separate dissent, Justice Jackson wrote that the judgment is ‘intolerable, unwarranted, and plainly antithetical to bedrock constitutional principles’. According to Justice Jackson, ‘the very idea of immunity stands in tension with foundational principles of our system of government’. The Court has now opted ‘to let down the guardrails of the law for […] any future president who has the will to flout Congress’s established boundaries’, she wrote.

Nixon-era precedents

For precedent, the justices on both sides looked to cases involving former President Richard Nixon, who in 1974 faced impeachment and resigned in disgrace amid the infamous Watergate scandal.

In United States v Nixon, a unanimous Court had ruled that President Nixon couldn’t claim executive privilege to shield damaging White House audio tapes from a subpoena by a special prosecutor. The Court rejected Nixon’s claim to ‘absolute, unqualified presidential privilege of immunity from judicial process under all circumstances’.

Neither the doctrine of separation of powers nor the generalised need for confidentiality of high-level communications, without more, can sustain an absolute, unqualified Presidential privilege of immunity from judicial process under all circumstances’, then Chief Justice Warren Burger wrote.

In Nixon v Fitzgerald in 1982, the former president had been successfully sued by an Air Force civil service whistleblower who was wrongly dismissed at Nixon’s direction. A lower court awarded money damages, but the Supreme Court sided with Nixon, ruling presidents are entitled to absolute immunity from civil liability for official acts.

Hypothetically now, under the new standard of immunity, a president wouldn’t be prosecuted for ordering the US Navy’s elite commandos to kill a political rival. Nor could they be held responsible for instructing the Justice Department to open sham investigations of political enemies. Although obvious abuses of power, both would shelter under the Court’s broad immunity shield.

President Joe Biden referred to presidential immunity for official actions as a ‘fundamentally flawed [and] dangerous principle’. He has suggested he’ll put forward a constitutional amendment to make presidents subject to the criminal code. He has also announced support for reform of the Supreme Court, including for a statute to cap the number of years a Supreme Court justice can hear cases for and to regularise appointments of new judges onto the Court, guaranteeing each president a certain number of picks.

William Roberts is a US-based freelance journalist and can be contacted at wroberts3@me.com