Are Qatar’s reform efforts falling short?

Abby Seiff

Across the Middle East, states have turned to migrant workers to fill significant labour shortfalls. This has left governments struggling to keep up with regulation and enforcement, leading to grave rights violations.

When Ranjit Kumar Sah finished his schooling in Nepal, Qatar was the natural next step. Though his village is so remote it takes half-an-hour to reach a paved road, it’s located in an area that has become one of the epicentres of Nepal’s labour migration boom. Between 2009 and 2015, migration from Dhanusha District more than doubled, and today it sends abroad more migrants than any other district. Nearly all go to the Gulf, and most go to Qatar.

For two years – the length of a typical contract – Sah worked as a construction worker. He carried bags of cement and rebar in the searing desert heat. Though the working day was set at eight hours, Sah and his colleagues frequently worked up to 12 in order to make more money. During the first ten months, Sah’s salary went to repaying a £750 loan taken out to pay a broker’s fee. Afterwards, he began sending money home to his family – the equivalent of about £124, nearly all of the £140 he earned most months.

‘It was a very hard job,’ Sah recalls. The 23-year-old had returned to Dhanusha for his wedding, and was hoping he could figure out a way to find a job at home to avoid going back to Qatar. ‘It was very hot in the daytime and very difficult to work.’

At the construction site, the Qatari bosses treated the labourers – primarily men from South Asia – with disdain. ‘Since we were just labourers, they didn’t see us on good terms. They made us work non-stop with no break at all, so it was very difficult,’ says Sah.

Accidents were common. One morning, Sah awoke to find his friend bleeding badly. Another broke his leg onsite. ‘Minor injuries were common. Myself, I got hurt too. Not a big accident, but you see a lot of people suffering.’

Migrant workers fill the shortfalls

Across the Gulf, states have turned to migrant workers like Sah to fill significant labour shortfalls. In Qatar, nearly 86 per cent of the population is made up of expatriate workers compared with an average of 49 per cent across the entire Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). In some ways, it is a win-win. Migrants come from countries with little home-grown industry or means of advancement. Remittances have helped economies flourish and have allowed families to educate their children and create otherwise unavailable opportunities.

But, meeting the fierce need for infrastructure growth with the import of millions of expatriate workers has left both receiving and sending governments struggling to keep up with regulation and enforcement, and has led to grave violations of human and labour rights. The laws, meanwhile, have fallen far short of the safeguards needed in an increasingly massive and complex labour system.

For years, Qatar instituted a particularly onerous kafala system, which kept workers legally bound to their employer-sponsors. Under the 2009 Sponsorship Law, workers could leave the country only if their employer consented to give them an exit visa, and could move to a new job following their contract end only when given a release letter by their employer. If they left without a release letter – even after the contract ended – workers were required to leave Qatar for two years before seeking employment with a new company.

Breaking these laws would result in fines, arrests and deportation. Proving an employer is abusive is no small feat and it is not unusual for exploitive employers to lay claims against their own employees before such a suit can be filed. In Doha, detention centres swell with deportees who have ‘abscond[ed] from abusive employers,’ in the words of François Crépeau, United Nations Special Rapporteur on the human rights of migrants. In his 2014 report on his mission to Qatar, Crépeau wrote: ‘The kafala system enables unscrupulous employers to exploit employees.’

In 2010, Qatar won a fierce bidding process to host the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) 2022 World Cup. In the intervening years, the population grew by nearly one million and stemming such violations became even more difficult. Indeed, even the Qatari government has noted as much, writing in its 2015 National Human Rights Committee report that ‘there is still an urgent need to an effective enforcement and application of the labour law along with the inspection system’.

The World Cup and its attendant billions of dollars worth of infrastructure, stadiums, hotels and centres have sent labour violations skyrocketing. Between 2010 and 2013, an estimated 1,200 people have died working in Qatar, according to figures from the International Trade Union Confederation, which has calculated that another 4,000 are likely to die due to poor working conditions by the time the World Cup kicks off in 2022. Because FIFA is a Swiss organisation, some have argued that developers face foreign liability. In January, the Commercial Court of Zurich threw out a lawsuit against FIFA filed by labour unions on behalf of migrant workers arguing that FIFA failed to protect them in Qatar. The case was dismissed on the grounds that ‘parts of the complaint… [were] too vague or not legal,’ according to broadcaster Deutsche Welle, but others have suggested further means of recourse.

Minor injuries were common. Myself, I got hurt too. Not a big accident, but you see a lot of people suffering

Ranjit Kumar Sah

Nepalese migrant worker in Qatar

In a 2014 article in the Hofstra Labor & Employment Law Journal entitled ‘A CN Tower Over Qatar: An Analysis of the Use of Slave Labor in Preparation for the 2022 FIFA Men’s World Cup and How the European Court of Human Rights Can Stop It’, lawyer Michael B Engle makes a case that the European Court of Human Rights could well have jurisdiction over Qatari abuses of third-country nationals. ‘Qatar workers are working for 2022 on explicit appointment from FIFA based in Switzerland. This is probably the most important variable,’ Engle tells Global Insight. ‘I cannot stress enough how disappointed I am that World Cup 2022 has not already been moved. It should be a public relations nightmare and we are years away.’

While the mounting body of evidence surrounding worker exploitation has prompted little action from FIFA, Qatar promised to take steps to reform its laws and enforcement. Late last year, the widely criticised kafala system was finally abolished and replaced by a labour law ostensibly focused onaddressing the shortfalls of the sponsorship law.

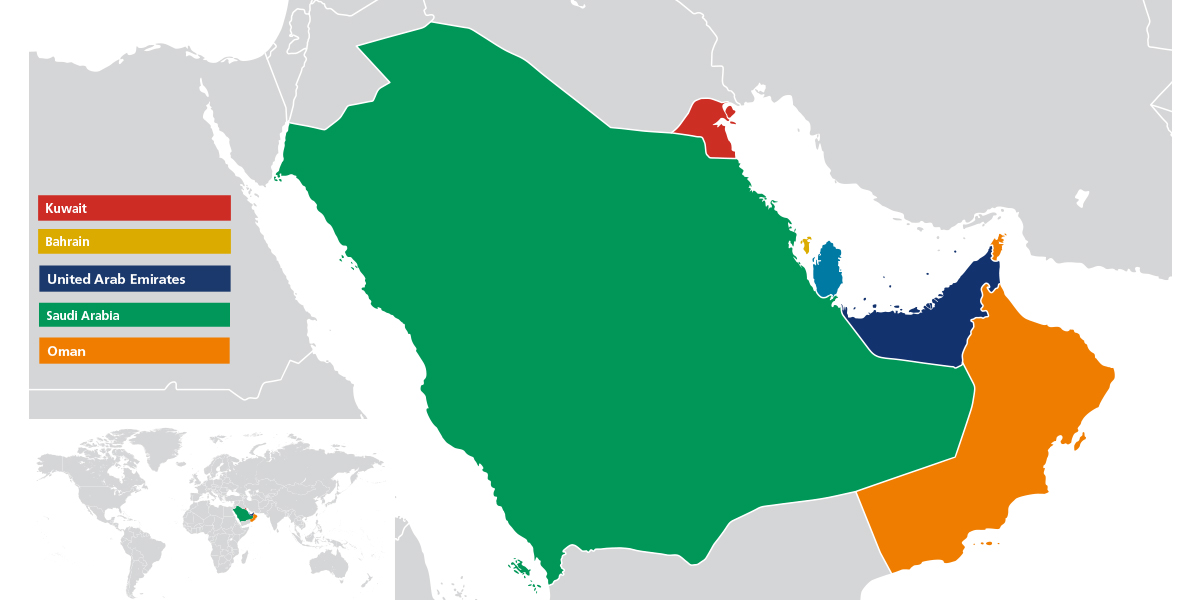

Qatar is hardly the only country in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) facing the challenges of balancing tradition, money and modernity. All of the GCC countries institute some form of the kafala system to regulate migrant workers, but a number have sought to reform their legislation in recent years.

Source: Gulf Research Centre, Human Rights Watch

Kuwait

A worker can transfer employer only with the permission of their boss or after three years employment, after changes to the law were put in place last year. It is one of the only countries in the region to offer some labour law protections for domestic workers. The law passed in 2015 goes farther than many of its neighbours’, mandating paid leave, minimum wage, a weekly day off and set working hours.

Bahrain

Bahrain was the first country to make substantive reforms to its foreign worker laws and is often lauded as a forerunner in the region. Workers are allowed to switch jobs without their original employer’s consent and their work permit doesn’t automatically expire at the end of the contract, allowing them time to seek new positions. No exit permit is required and multiple entries are permitted.

United Arab Emirates

The United Arab Emirates has revised its law several times to permit employees to transfer jobs without employer permission under certain circumstances. Workers do not need a permit from their employer to exit the country. Employers are responsible for paying the cost of worker repatriation at the end of their service.

Saudi Arabia

The country undertook a major overhaul of its Labour Law in 2015, strengthening penalties and enforcement, and increasing paid leave, worker compensation and other aspects of the law. Workers are still required to obtain an exit visa from their employer. Employees can transfer without their employer’s permission under a number of circumstances.

Oman

Workers need permission to transfer employer during their two years of service, or else they must leave the country for two years. If they wish to transfer after two years of work, they need approval of both the employer and the government. Under the law, employers must pay for their employees to return to their home countries at the end of their service.

Construction workers rest during their lunch break in Doha.

Ghada M Darwish, Managing Partner at her eponymous law firm in Doha, is an officer of the International Bar Association’s Arab Regional Forum, has previously worked for the Qatari government’s National Human Rights Committee and has spent years working on criminal, civil and labour law. She called the law a ‘strategic move’ by the Qatari government and appeared confident the reforms would address the concerns of critics. ‘It is a very good gesture of the government towards the foreigners and migrant workers in Qatar. It is more significant at the international level in the context of the upcoming World Cup in 2022,’ she says.

‘The new law will help expatriates to choose jobs carefully and it confers more responsibility on the ministries and other competent authorities while dealing with employment issues. The exit permit procedure is simplified and employees can directly approach the ministries if there is a dispute with the employer regarding exiting the country.’ Many, however, are not convinced.

‘Modern-day slavery’

In an Amnesty International report on the legislation titled ‘New Name, Old System?’ the group argues that the new law does little to safeguard against endemic worker exploitation. ‘What is certain is that the new law does not abolish the exit permit system and leaves employers with excessive control over people working for them during the period of their contract, which can last up to five years. The law may make it easier for workers to return to Qatar for new jobs after they have left, a potentially important improvement, but on the other hand, it also appears to make it easier for employers to hold workers’ passports against their will. Ultimately, the powers of the “employer” under the new system are similar to those of the “sponsor” under the old one,’ notes the report.

Doctor Aidan Hehir, a reader in International Relations at the University of Westminster, has researched Qatar and its rights obligations and is also ‘not overly optimistic’ that its reforms are genuine. ‘When I visited Qatar, I observed first-hand what amounts to a system built on modern-day slavery,’ he says. ‘Quite how that system can sustain itself without slavery is beyond me, so I don’t see that the billionaires are going to do much more than what it takes to give an appearance of reform. That’s essentially what Qatar’s position on human rights more generally is; they are skilled at saying the right things and employing public relations firms who can spin the news in a certain way but, on the ground, it’s a very different story.’

[Abolishing the kafala system] was a very good gesture of the government towards the foreigners and migrant workers in Qatar

Ghada M Darwish

Managing Partner, Ghada M Darwish Law Firm,

Doha and Officer of the IBA Arab Regional Forum

That ability to whitewash the situation on the ground, argues Hehir, has allowed Qatar to retain a veneer of respectability. This year, for instance, Qatar will host the 7th meeting of Responsibility to Protect (R2P) Focal Point. R2P is an agreement made by UN member states in 2005 to prevent against genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and ethnic cleansing. Joining and touting this type of non-binding agreement nevertheless allows Qatar to be seen as a regional leader. ‘They get to present themselves on the world stage as responsible, progressive and responsive to external norms,’ Hehir says. ‘Obviously they want to use this publicity to counter the negative (true) stories about them and make opponents seem wrong or ill-informed.’

Entering the world stage with mega projects like the World Cup is just one facet of Qatar’s efforts to improve its global status.Hosting international events like the R2P Focal Point, and hosting outposts of foreign universities like Georgetown and Northwestern, are all part of a roadmap to make Qatar into a world-class nation, as outlined in National Vision 2030, a development plan launched by the Emir in 2008. The 30-page National Vision charts human, social, economic and environmental development over the next two decades with the aim of ‘transforming Qatar into an advanced country by 2030, capable of sustaining its own development and providing for a high standard of living for all of its people for generations to come’.

‘As a part of the National Vision 2030, the government is heading towards sustainable development and consistent growth,’ says Darwish, who also dismissed some of the international media criticism as propaganda. ‘The Qatar government is very keen on its residents’ affairs and is taking every earnest step to hear and resolve the issues that come its way in a speedy and effective manner,’ she says.

When I visited Qatar, I observed first-hand what amounts to a system built on modern-day slavery

Aidan Hehir

Reader in International Relations, University of Westminster

Indeed, the National Vision 2030 document reads like a blueprint for utopia, with the government vowing to preserve cultural and national identity while championing civil rights and social progress within a rapidly developing, environmentally-friendly economy. Protection of foreign workers, increased opportunities for women, tolerance and openness all get a mention. On the Qatar National Vision website, the document can be accessed in multiple languages, including sign language.

Eight years after its launch, however, the reality falls far short of this ideal. About half the female population is in work, and not a single woman is in Parliament at the moment. Under Qatar’s family law, women are still obliged to ‘take care and obey’ their husbands – a stipulation not outlined for men. Sodomy can be punishable by several years in prison and extramarital relations can be punishable by flogging.

The Supreme Judicial Council is appointed by the Emir and political parties are banned. Legislative elections have yet to take place. In the latest Freedom House index, the country is rated ‘not free’. ‘The head of state is the emir, whose family holds a monopoly on political power. The emir appoints the prime minister and cabinet, and also selects an heir-apparent after consulting with the ruling family and other notables,’ the report notes. Elections for members of Qatar’s legislative branch, the Advisory Council, were stipulated in the 2003 constitution but have been postponed repeatedly.

While press freedom and free expression areenshrined in the constitution, the situation in practice is more complicated. Both academia and the media practice a significant amount of ‘self-censorship’, noted the 2015 US Department of State human rights report on Qatar. Criticism of the Emir is punishable by up to five years in prison and a 2014 cybercrime law has been used to target the outspoken. ‘I believe these laws exist to primarily protect royals, ministers, governmental officials and those who are powerful. This is very, very dangerous,’ rights lawyer and former Justice Minister Najeeb Al Nuaimi told Doha News. ‘The cybercrime law is, in reality, like a knife held close to the necks of writers, activists and journalists. It is a tool of intimidation.’

Doha News, an independent, English-language news outlet with millions of readers, last year saw its website blocked for several days and an editor detained overnight.

And yet, the existence of a website like Doha News and Al Nuaimi’s very ability to say such things on a public forum shows the needle Qatar is trying to thread. While some can view such things purely cynically as Qatar trying to brighten its public image, others point to efforts like its labour law reform as proof of genuine attention. In its National Vision document, the government calls Qatar ‘at a crossroads’. The coming years will see which way it turns.

Abby Seif is a freelance journalist and can be contacted at aseiff@gmail.com

Additional reporting by Pragati Shahi. Abby Seiff reported from Nepal on a fellowship from the International Reporting Project (IRP).