India rolls out the red carpet

Stephen Mulrenan

Foreign investment is undeniably on the rise. But, despite abolishing many hundreds of archaic laws, Prime Minister Narendra Modi remains under pressure to do more.

When Narendra Modi delivered the opening plenary address in Davos, Switzerland on 23 January, he was the first Indian prime minister to attend the annual World Economic Forum meeting in more than 20 years. Modi’s decision to speak on the need for global solutions to issues such as climate change, terrorism and anti-globalisation was all the more significant as it followed Chinese President Xi Jinping’s memorable address at the same conference last year.

Like Xi before him, Modi defended globalism and emphasised his concern that many countries were taking their lead from United States President Donald Trump’s ‘America First’ policies and becoming more self-centred. Unlike Xi, however, he disappointed many in the audience of business leaders and heads of state by failing to offer an alternative vision of global leadership to tackle the world’s most pressing issues. Instead, Modi delivered a strong ‘Invest in India’ pitch by highlighting the reforms and policies that his administration had undertaken to attract more foreign investment (such as apparently abolishing some 1,400 archaic laws). ‘We are removing red tape and laying the red carpet,’ he said.

By emphasising Indian values and democratic traditions as the country’s global selling point and a force for stability during a time of uncertainty, Modi’s pitch has since been interpreted as a deliberate attempt to distinguish his country from China.

World Bank gross domestic product (GDP) figures suggest India and China will unequivocally power the global economy for the foreseeable future. And, while indirectly comparing democratic New Delhi to authoritarian Beijing was considered by some observers to be a smart move, others interpreted the public relations push as reflecting a lack of confidence and a need to proactively court foreign investment.

Sridhar Gorthi, a corporate partner with Trilegal in Mumbai, concedes that comparisons are not straightforward due to differences in the commercial and regulatory landscapes of the two countries. He nevertheless emphasises that ‘India has – to its advantage – a tradition of rule of law that leads to greater predictability and fairness in legal outcomes.’

Red tape

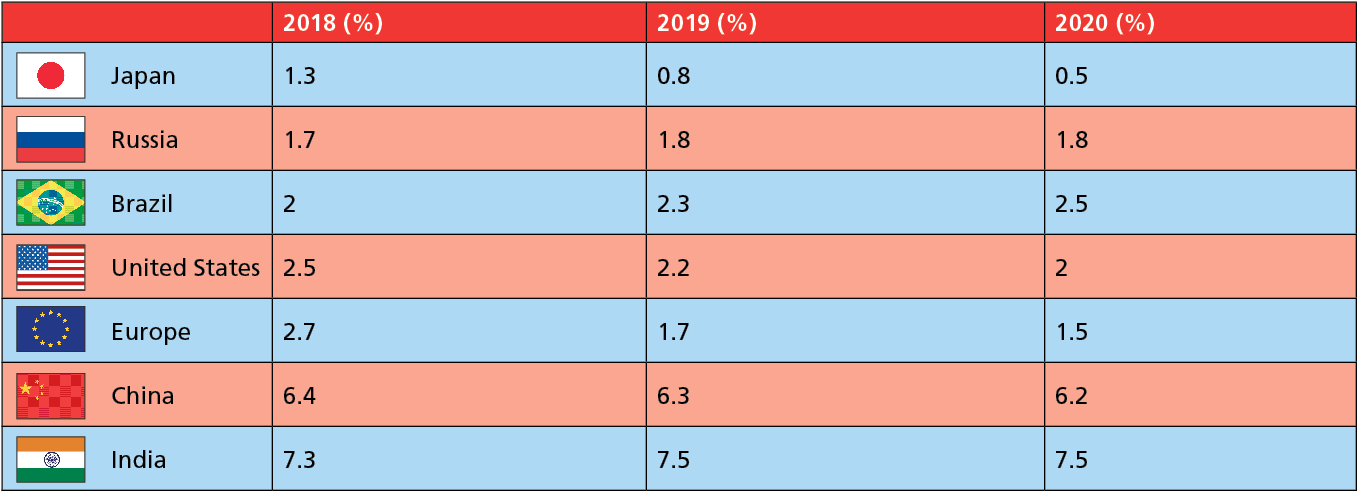

Over the past few years, Asia’s third-largest economy – behind China and Japan – has delivered strong economic growth. According to the World Bank, India’s GDP growth has recovered from a three-year low and its economy will lead the pack for the next three years (see box: GDP growth projections suggest India will lead the pack).

India has – to its advantage – a tradition of rule of law that leads to greater predictability and fairness in legal outcomes

Sridhar Gorthi

Corporate partner, Trilegal

Potentially strong gains in private consumption and services as well as a recovery in private investment is expected to drive GDP growth. Meanwhile, the World Bank has praised the Modi administration for successfully controlling the country’s fiscal deficit, laying the foundation for India’s bullish stock market.

But it is Modi’s efforts to foster foreign direct investment (FDI) across numerous sectors of the Indian economy that has garnered the most accolades, although it should come as no surprise. When seeking power in the general election of May 2014, Modi played heavily on his track record of creating a high rate of GDP growth as Chief Minister of Gujarat, where he topped the World Bank’s ‘Doing Business’ rankings among Indian states for two consecutive years and created special economic zones to attract foreign investment.

Following a record-breaking year for M&A activity in 2016, during which there were 421 deals worth $59.7bn, deal value and volumes remained strong last year – 379 deals worth $54.7bn was still the second-highest annual total of M&A deals by value recorded since 2001.

Domestic M&A continued to dominate activity, while inbound transactions were slightly down in 2017 from the year before (187 deals worth $23.5bn compared to 195 deals worth $30.3bn).

Mumbai-based Rabindra Jhunjhunwala is Secretary of the IBA’s Current Legal Developments Subcommittee of the Corporate and M&A Law Committee and a partner with Khaitan & Co. ‘Since the incumbent government has assumed power, India has witnessed substantial policy changes and regulatory liberalisation that has demonstrated a strong political will to provide impetus to inbound investments,’ he says.

A great deal of the ‘red tape’ was removed when the Modi administration significantly relaxed the country’s FDI laws in 2017. Although this involved a number of initiatives, perhaps the most significant was replacing the main regulatory body dealing with foreign investments (the Foreign Investment Promotion Board or FIPB) with a new administrative body to facilitate FDI applicants (the Foreign Investment Facilitation Portal or FIFP).

Under the new regime, which was designed to ease the flow of FDI by removing a layer of decision-making, government approval thresholds for industry sectors such as civil aviation, manufacturing and single brand retailing were modified, with many other sectors no longer requiring any prior approval.

The Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion (DIPP) also introduced a detailed ‘standard operating procedure’ for investments, leading to a more streamlined process and expeditious timeline for approvals (no more than ten weeks). And rules around limited liability partnerships were relaxed, which will likely make them a more attractive investment vehicle for FDI. The ways foreign investors can get involved with startups were also broadened.

Beneficial impact

Other key structural changes to the legal and regulatory landscape introduced by the Modi administration over the last few years include: new insolvency laws designed to make insolvency and bankruptcy procedures more efficient; the most significant tax reform since independence in the shape of a new consumption tax; and myriad other changes that may not have received as much attention but have had an equally positive impact on the country’s economy.

The new Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) was introduced in a phased manner from August 2016 but it wasn’t until last year that its impact was fully felt. Domestic buyers in particular were quick to take advantage of the new legislation governing non-performing assets (NPAs), which has enabled them to acquire distressed assets at favourable valuations.

GDP growth projections suggest India will lead the pack

Source: World Bank

Bill Carr, Head of the India desk at CMS Cameron McKenna in London, says: ‘A lot of M&A activity is being driven by the new insolvency regime, where banks are looking at their non-performing loan portfolios and starting the insolvency process, which is leading to auctions.’

Foreign investors have, to date, been more cautious and have tended to stay away from these auctions, although this is starting to change. For example, in December 2017, US private equity firm KKR established a 100 per cent foreign-owned asset reconstruction company to invest in distressed assets. And, in March 2018, UK industrial company Liberty House was announced as the successful preferred bidder for assets of Amtek Auto, one of the largest auto component manufacturers in India.

Jhunjhunwala says the IBC has sought to create a level playing field between family promoters (who still continue to dominate Indian businesses) and investors. ‘It has bolstered the climate for transparent, orderly and time-bound bankruptcies and generated excitement in global funds while evaluating distressed assets in India,’ he says.

Abhijit Joshi, Founding Partner of Veritas Legal in Mumbai, is confident that foreign investors will show greater interest in distressed assets in India as implementation of the IBC progresses and the efficiency of the new procedures is demonstrated. ‘This will create a big market for FDI in distressed funds and enable banks to reduce NPAs and recover substantial amounts of bad debts,’ he says.

Although the M&A market in India remained resilient in 2017, problems around implementation of a much-anticipated initiative to bring indirect taxation under one umbrella did lead to temporary slowing of growth.

On 1 July 2017, India finally replaced its multiple federal and state tax laws with a single harmonised Goods and Services Tax (GST). Although the GST was designed to reduce administration, increase tax revenues and create a seamless indirect tax regime that consolidated the existing range of taxes, its roll out faced a lot of criticism.

In particular, small businesses – which represent almost half of India’s economy – struggled to adapt to the new levies, with many reporting reduced profits as a result of increased compliance costs, supply chain disruptions and policy changes. Although some of India’s larger companies used the disruptions to gain market share, the Modi administration has since taken the necessary corrective measures.

Jhunjhunwala says that introduction of the GST has provided a welcome change following notorious episodes such as the Vodafone case on retrospective taxation. ‘Aside from enhancing ease of compliance and reduction in costs by eliminating the cascading effects of taxes, GST has been critical in establishing a predictable, stable and transparent tax administration,’ he says.

The World Bank has also been full of praise for the long-awaited initiative and it was no surprise when India jumped a record 30 places in the Bank’s 2017 ‘Doing Business’ rankings, which factor in, among other things, the tax regimes of countries.

Carr says that the transport sector, for one, will benefit from introduction of the GST. ‘There will now be foreign investment in businesses that are consolidating distribution centres, for example, as one of the key issues with transporting farm produce is the amount that rots on the way from the farm to the market.’

Tackling the tax dodgers

Tackling tax avoidance has also been a dominant theme of the Modi administration, and India finally joined countries like Australia, Canada, China and South Africa when it adopted General Anti-Avoidance Rules (GAAR) on 1 April 2017. Originally proposed to be implemented on 1 April 2012, the GAAR allows the tax authorities to deny tax benefits on transactions executed with the purpose of avoiding taxes (eg, via shell companies and tax haven jurisdictions).

The adoption of GAAR followed Modi’s controversial decision, in November 2016, to crack down on corruption and illegal cash holdings by withdrawing high value currency notes from the financial system. The move, which came to be known as ‘demonitisation’, saw the removal of 500 rupee and 1,000 rupee notes.

‘The aim was to bring a lot of ‘black’ money back into circulation as well as get rid of counterfeit money,’ says Carr. ‘A more cynical view might be that it also restricts some political parties from buying votes.’

Although the consensus among analysts, economists and politicians is that the demonitisation initiative was a failure and contributed to a slowdown in economic growth, it did have a positive impact on FDI into Fintech businesses.

Meanwhile, despite India having a relatively slow court process, the Modi administration has been pushing hard to have international arbitrations conducted at the Mumbai Centre for International Arbitration. For example, several amendments to the 1996 Arbitration and Conciliation Act have been introduced in the last few years to improve the enforcement of foreign awards, put in place timelines and streamline arbitration procedures. Specialised commercial courts have also been introduced. Gorthi suggests that the benefit of these amendments can be seen in recent cases such as Ranbaxy Daiichi, Tata DoCoMo and others.

Substantial policy changes and regulatory liberalisation has demonstrated a strong political will to provide impetus to inbound investments

Rabindra Jhunjhunwala

Partner, Khaitan & Co; Secretary,

IBA Current Legal Developments Subcommittee

Finally, the two other key legislative developments under Modi have been the 2016 Real Estate (Regulation and Development) Act, which is expected to throw up opportunities for investment in greenfield and brownfield real estate projects, and the 2017 Companies (Amendment) Act.

The latter introduced a number of changes designed to address issues around implementation of the 2013 Companies Act. The resulting amendments sought to ease corporate governance while continuing to ensure the protection of investors and other stakeholders.

India’s M&A bonanza: standout deals of 2017

Vodafone-Idea Cellular: Vodafone’s $12.7bn merger of its India business with Idea Cellular to become the leading communications provider in India with almost 400 million customers.

SoftBank-Flipkart: SoftBank’s acquisition of a 20 per cent stake in Flipkart (one of India’s biggest online retailers) for $2.6bn. The investment formed part of a financing round where Flipkart also raised capital from premier technology companies Tencent, eBay and Microsoft.

Claris Injectables: Baxter International acquired Claris Injectables Limited, a global generic injectables pharmaceutical company, for $625m.

GIC-DLF: GIC’s acquisition of a 33.33 per cent stake in DLF’s rental business, DLF Cyber City Developers for $1.4bn.

Bharti Airtel-Millicom: Indian telecommunications company Bharti Airtal entered into a joint venture with Swedish telecommunications and media company Millicom. Both parties agreed to contribute certain existing offshore telecommunications businesses to create a combined entity that is expected to have revenue close to $300m.

Reliance Communications: Brookfield Infrastructure acquired Reliance Communications’ telecommunications towers business for $1.6bn (the largest investment by an international financial investor in the infrastructure sector in India).

Bain Capital-Axis Bank Ltd: Bain Capital’s acquisition of a 5.55 per cent stake in Axis Bank for $1.8bn, one of the largest private equity investments in the Indian banking sector.

Source: Herbert Smith Freehills

Although India has improved its corporate governance framework over the last few years, with the aim of encouraging FDI, one or two corruption scandals have recently come to light that have dented investor confidence.

For example, in February, diamond jeweller Nirav Modi, founder of Firestar Diamond, was accused of perpetrating a $1.8bn fraud (India’s largest ever) by state-owned Punjab National Bank.

Rukshad Davar is Partner and Head of M&A at Majmudar & Partners in Mumbai. ‘If the government were to take actions expeditiously in respect of recent corruption scandals,’ he says, ‘such as expediting trials, having special courts for hearing such matters and having a speedy conclusion to such matters, this would further generate confidence for foreign investors to invest in India.’

Gorthi agrees. ‘As levels of compliance and accountability increase, it is inevitable that some of the unhealthy practices of the past will progressively be rooted out,’ he says. ‘However, significant further reforms must be introduced in the banking sector to curb NPAs and free up the flow of capital to support India’s growing economy.’

In a bid to increase transparency, representation and accountability in the existing corporate governance regime, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) is all set to amend the listing obligations and disclosure requirements applicable to listed Indian companies. This follows its acceptance of most of the recommendations made by a committee chaired by Uday Kotak.

The Kotak Committee recommendations also tighten the rules around party contracts, which will have a positive impact on investors. ‘The recommendations are bringing more international standards into the governance of listed companies in India,’ says Carr. ‘That’s good for foreign investors and it’s good for companies trying to attract foreign investment.’

Expansive incentives

Modi’s thrust on opening up the Indian economy to foreign investment and his efforts at making the approval process more streamlined has led to a notable increase in FDI inflow. This has caught the attention of global organisations such as IKEA and SAIC Motor Corporation, to name a few, who have announced plans to enter India.

Modi has also offered expansive incentives to startups through government schemes such as ‘Make in India’ (launched in September 2014 to transform India into a global design and manufacturing hub), ‘Skill India’, ‘Digital India’, ‘Startup India’ and ‘Stand Up India’. ‘This has helped India gain recognition among global startup ecosystems,’ says Jhunjhunwala.

But, despite these initiatives, some business leaders say that a lot more needs to be done to attract more investment – such as tackling corruption more effectively, controlling bureaucracy and combating pollution.

A lot of M&A activity is being driven by the new insolvency regime, where banks are looking at their non-performing loan portfolios

Bill Carr

Head of the India desk,

CMS Cameron McKenna

The Modi administration has indicated that a new industrial policy is likely to be enacted soon in order to promote foreign technology transfer and boost technological innovations. A task force to develop a national policy on e-commerce has also been proposed. And the government continues to inch closer to implementing the 2013 Lokpal and Lokayuktas Act, a statute promoting an anti-corruption body and an ombudsman to look into corruption allegations of all public administrators and legislators.

However, looming large on the horizon is next May’s general election, in which Modi is expected to win a reduced majority. ‘The focus is now very much on domestic issues and keeping voters happy,’ says Carr. ‘There won’t be much appearing on the legislative agenda for foreign investors until after the general election.’

Whatever the outcome, all agree that stability is of utmost importance to foreign investors. ‘While emerging economies will seek FDI for contribution to their own employment and GDP growth,’ says Jhunjhunwala, ‘investors in return will look for high-growth yet stable economies that do not experience uncontrolled growth, resulting in economic bubbles and consequent financial crises.’

With sectors previously operated by government now being opened up for privatisation, India not only has the potential to match China but continue to outperform it – and other countries – by offering foreign investors previously untapped opportunities.

Stephen Mulrenan is a freelance journalist. He can be contacted at stephen@prospect-media.net