The increasing popularity of private funds

Back to Securities Law Committee publications

Jerry Koh

Allen and Gledhill, Singapore

jerry.koh@allenandgledhill.com

Jonathan Lee

Allen and Gledhill, Singapore

jonathan.lee@allenandgledhill.com

An initial public offering and public listing of a company’s shares remains a key milestone and goal that many companies aspire to in their corporate fundraising journey. However, in this age of unicorns – and now decacorns – there has been a tremendous growth in private equity relative to the public markets to support early-stage and growth capital start-ups.

According to McKinsey’s Global Private Markets Review 2020, global private market assets under management (AUM) has grown by approximately 170 per cent over the past decade. In comparison, over the same period, public market AUM increased by 100 per cent. The growth in private market AUM has been fuelled by private equity capital targeting investments in the Asia-Pacific region which, according to Ernst & Young’s July 2019 PE Pulse report, has climbed at a compounded rate of 21 per cent over the last decade, compared to seven per cent for Europe and seven per cent for North America.

Against this backdrop, Singapore stands well placed as a key gateway for global private market investment in Asia. The establishment of private investment funds which are either managed from, and/or domiciled in, Singapore has become increasingly popular as a means of tapping the large capital inflows into Asia.

This article provides an overview of the various vehicles available for the structuring of private funds.

Structuring of private funds

Traditionally, private investment funds in Singapore have been structured either as limited partnerships, unit trusts or private limited companies. With the launch of the variable capital companies (VCC) framework in January 2020, the array of available investment fund structures in Singapore has now broadened to include a variable fund structure comparable to other segregated portfolio and protected cell structures in offshore fund domiciles such as the British Virgin Islands, the Cayman Islands and Guernsey.

Seen as a potential game-changer in Singapore’s continued push to cement its status as an Asian wealth and fund management hub, the VCC plugs a gap in the Singapore fund ecosystem and provides fund managers with additional options to structure and domicile their funds in Singapore. This is timely given Singapore’s robust growth in AUM, with many funds both onshore and offshore already being managed out of Singapore.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to determining the optimal structure to adopt for a private fund. Fund managers need to weigh not only tax and legal considerations, but also the requirements of the target investor pool, investor familiarity with the structure and ongoing compliance costs and obligations.

An overview of the various available fund structures in Singapore and some of the pros and cons that fund manager and investors should take into account when structuring private funds are set out below.

Variable capital companies

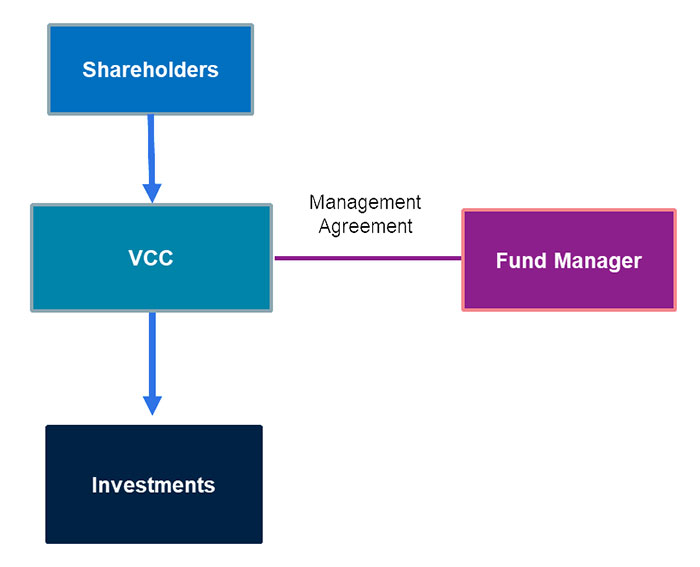

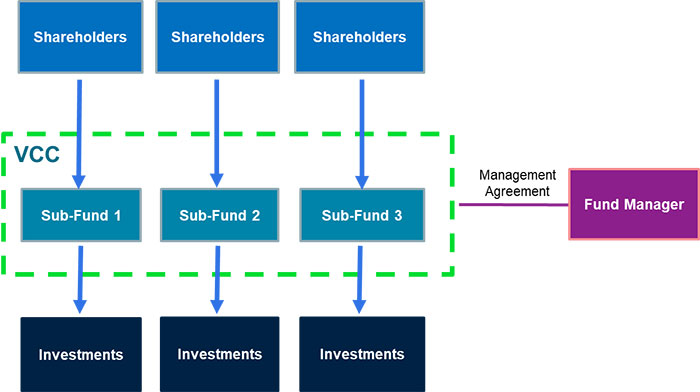

Variable capital companies are corporate vehicles which can only be used as investment funds. They can be structured either as a standalone fund or as an umbrella fund with multiple sub-funds having segregated assets and liabilities. Figure 1 and Figure 2 set out the structures of a typical standalone VCC and umbrella-sub-fund VCC respectively.

Figure 1: Standalone VCC

Figure 2: Umbrella-sub-fund VCC

Variable capital companies have been designed to overcome some of the limitations of the traditional company. As its name suggests, a VCC can vary its capital structure easily through redemption of its capital, allowing investors to realise their investments without having to be subject to capital reduction procedures. A VCC can also pay dividends from its capital, in contrast to companies which are only permitted to pay dividends out of profits.

Variable capital companies also provide fund managers with the flexibility to pursue multiple strategies and segregate investments between different pools of investors, while maintaining a single legal entity. To illustrate, a fund manager would be able to establish a new sub-fund with different investment strategies, asset portfolios and investor pools simply by registering the sub-fund with the Accounting and Corporate Regulatory Authority (ACRA), the national company registry. Previously, it may have had to set up an entirely new fund. The umbrella-sub-fund structure also allows for sharing of a common board of directors and service providers, thereby reducing costs and enjoying economies of scale.

The Variable Capital Companies Act, No. 44 of 2018 (VCC Act), the legislation governing VCCs, provides that the assets of a sub-fund cannot be used to discharge the liabilities of any other sub-fund and that each sub-fund is to be wound up singly and separately from each other as if it were a separate legal entity, thereby providing statutory ring-fencing of each sub-fund’s assets and liabilities in the event of insolvency.

Variable capital companies cater to the concerns of private fund investors regarding confidentiality. While the register of members of a VCC need to be disclosed to the relevant regulatory authorities on request, such details need not be made publicly available. The constitution of the VCC is also not publicly available unlike companies. One potential drawback is that an umbrella VCC is required to provide financial statements containing separate accounts of each of the sub-funds to all members of the VCC; members of the VCC with shares in one sub-fund would, therefore, have access to the financial statements of other sub-funds. This was noted by the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) during the public consultation process on the VCC. This requirement may perhaps be due to the novelty of the structure as well as the MAS wanting to ensure that all investors in a VCC are fully cognisant of its overall assets and liabilities. This also promotes clarity and transparency in the segregation of the assets and liabilities of each sub-fund and to ensure that there is no commingling.

To ensure robust levels of governance and oversight, a VCC is also required to appoint a fund manager that is regulated by the MAS.

Singapore limited partnerships

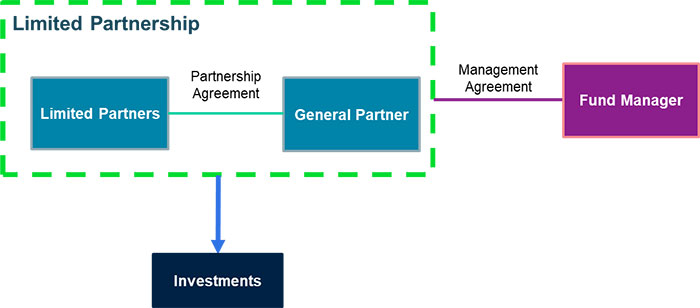

Prior to the introduction of the VCC, limited partnerships were generally seen to be the most suitable vehicle for private funds and consequently are also what investors are most familiar with. Singapore limited partnerships are governed by the Limited Partnerships Act, Chapter 163B of Singapore and consist of at least one general partner and one limited partner. An individual or a corporation may be a general partner or a limited partner. Figure 3 sets out the structure of a typical fund structured as a limited partnership.

Figure 3: Limited partnership structure

Generally, a limited partner’s liability for the debts and obligations of the limited partnership is limited to the amount of its agreed contribution, unless the limited partner takes part in the management of the limited partnership. On the other hand, the general partner is responsible for management of the limited partnership and is liable for all debts and obligations of the limited partnership incurred while it is a general partner. For this reason, general partners are usually set up by fund sponsors or principals of the fund manager as special purpose vehicles to ring-fence potential liabilities. A limited partnership does not have separate legal personality and the general partner enters into agreements and holds assets on behalf of the limited partnership, in its capacity as the general partner.

Similar to limited partnerships in many jurisdictions, one key characteristic of Singapore limited partnerships is that they are treated as tax transparent vehicles; tax is not levied at the limited partnership level but the share of income accruing to each partner will be taxed at the rates applicable to each of them respectively.

The partnership agreement governs the relationship between the partners of a limited partnership. The contents of the partnership agreement are lightly regulated by the Limited Partnerships Act, allowing greater flexibility compared to a company structure. In particular, the constraints regarding return of capital and distribution of profits are not present for limited partnerships.

Limited partnerships are not required to file their accounts with ACRA: where a private fund structured as a limited partnership is managed by a licensed fund manager, the particulars of the limited partners of the fund need not be made publicly available. These are features which lend themselves to the nature of investment funds where privacy is often a key consideration.

A comparable vehicle in an offshore jurisdiction is the Cayman Islands limited partnership, which is a common fund vehicle used for private equity funds, largely due to its tax neutrality and relative flexibility. Ultimately, the choice of domicile depends on multiple factors, including tax, regulatory and cost considerations. We have observed a trend of funds moving away from offshore jurisdictions to domiciles where the fund manager is located, where economic substance requirements are easily met and which provide favourable tax treatment, such as Singapore.

Unit trusts

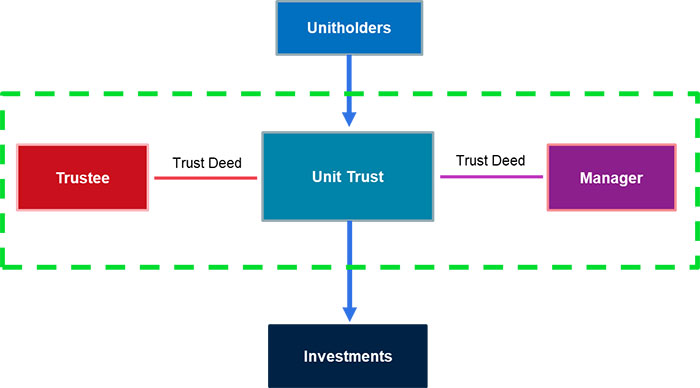

A private fund may be set up in the form of a unit trust. This is constituted by the execution of a trust deed, with legal ownership of the trust property (comprising the underlying assets of the private fund) being vested in a trustee. Figure 4 below sets out the structure of a typical fund structured as a unit trust.

Figure 4: Unit trust structure

An advantage of the trust structure, being a largely contractual arrangement, is its flexibility. The applicable legislation for Singapore trusts is the Trustees Act, Chapter 337 of Singapore, although they are lightly regulated and are not subject to extensive statutory requirements – such as those relating to maintenance of capital or distribution of profits – thereby allowing the fund to structure its redemption and distribution mechanisms to suit the commercial requirements. The trust structure would also potentially allow the nominees of the investors sitting on an investment committee at the trust level to be better insulated from potential fiduciary liabilities arising out of making major decisions, unlike a corporate structure where the issue of director’s duties may potentially arise under the Companies Act, Chapter 50 of Singapore (Companies Act).

While investors may be less familiar with a trust structure compared to limited partnerships, an increasing number of Singapore fund managers are utilising trust structures for their private funds, which is appropriate particularly if one of the exit strategies is to potentially list the private fund as a registered business trust or a real estate investment trust (REIT) on the Singapore Exchange. This avoids having to subsequently transfer the assets to the registered business trust or REIT, which may attract transfer taxes or give rise to other tax liabilities. Singapore’s burgeoning reputation as a global REIT hub for REITs with overseas assets means that this exit strategy can be applied by private funds holding real estate across different asset classes and jurisdictions.

Singapore companies

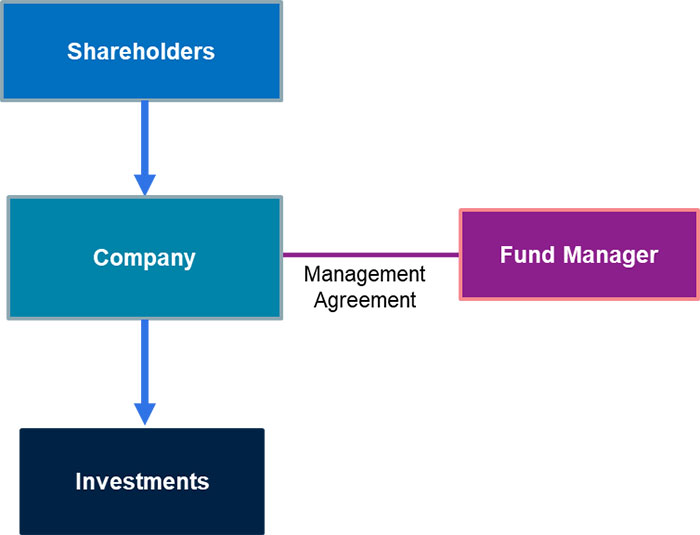

A private fund may be set up in the form of a Singapore private limited company incorporated under the Companies Act. A company has a separate legal personality and its obligations are ring-fenced from its shareholders, who enjoy limited liability status. Figure 5 below sets out the structure of a typical fund structured as a company.

Figure 5: Company structure

Although a fund manager would be appointed to manage the operations and business of the company, the board of directors is ultimately responsible for the company’s business and affairs. In addition, directors also owe fiduciary duties to the company. To ensure better oversight and governance, investors may want to appoint a nominee to the board of the company. However, this will need to be balanced against the additional obligations and liabilities which a nominee director may need to take on.

Companies also tend to be subject to more restrictive statutory requirements under the Companies Act, which may hamper the ability of the private fund to meet the investment objectives of investors. For example, there are restrictions on the return of capital to shareholders, such as requiring whitewash approvals for capital reduction and only allowing dividends to be paid out of profits. This makes it more difficult for investors to exit their investments and realise returns in a timely fashion. In addition, a company will generally need to comply with more stringent administrative and audit requirements, such as holding annual general meetings and filing returns with ACRA.

Despite these drawbacks, company structures are still a viable option for reasons such as ease of establishment and familiarity, and they tend to be used in more joint venture-type club deals where there are fewer investors.

Tax incentives

A key driver that has made it conducive to establish private funds and fund management platforms in Singapore is a favourable tax regime, encompassing a comprehensive range of double taxation treaties and tax incentives. Generally, the tax incentives exempt the fund from tax on certain specified income from designated investments. The main tax incentives for private funds in Singapore are as follows.

Offshore Fund Scheme under section 13CA of the Income Tax Act, Chapter 134 of Singapore (ITA)

This scheme is available to offshore funds managed by Singapore-based fund managers which will be exempt from tax on income and gains from investments such as stocks, shares securities, derivatives and so on. Offshore funds which are not resident in Singapore and not wholly owned by Singapore investors would generally be eligible for this scheme.

Resident Fund Scheme under section 13R of the ITA

This scheme affords Singapore resident funds the same tax exemption that an offshore fund qualifying under the Offshore Fund Scheme above would enjoy, to encourage fund managers to base their funds in Singapore. Use of this scheme by a fund is subject to MAS’s approval; the conditions include the fund being a Singapore-incorporated company, the fund manager being regulated by the MAS, the fund appointing a Singapore-based fund administrator and incurring minimum annual local expenditure.

Enhanced-Tier Fund Scheme under section 13X of the ITA

This scheme is available to both offshore as well as Singapore funds, regardless of the legal form (ie, applicable to VCCs, limited partnerships, trusts and companies), subject to approval from MAS. Some of the conditions that need to be met are a minimum fund size of S$50 million at the time of application, incurring minimum annual local expenditure and having a Singapore-based manager that employs at least three investment professionals in Singapore.

In addition, fund managers regulated by MAS may also apply under the Financial Sector Incentive (Fund Management) Award, which affords a concessionary tax rate of ten per cent to the fund manager for fund management and investment advisory services provided to funds which are under one of the tax incentive schemes above. To avail itself of this incentive, the fund manager is required to have at least US$250 million of AUM: the MAS also takes into account other qualitative criteria such as AUM growth targets, business spending and the number of investment professionals employed.

Conclusion

The use of private investment funds is becoming increasingly popular as a means to raise and deploy capital. At the 2019 Greenwich Economic Forum, the co-founder and co-executive chairman of the Carlyle Group, David Rubenstein, remarked that Singapore may be the best place to start a private equity firm because the greatest growth in the world is going to be in Asia.

Coupled with its pro-business environment, transparent and robust regulatory regime and continued government support through tailored investment structures, tax incentives and extensive double taxation treaties, Singapore is well-poised to capitalise on the growth in AUM in Asia-Pacific.

Back to Securities Law Committee publications