Sleepwalking into another crisis

Jonathan Watson

Despite the fall of the Lehman Brothers, the dramatic events of the financial crisis and its dreadful consequences, major banks continue to find themselves engulfed by scandal. Regulatory weakness and a lack of political will are just two of the reasons why it might not be long before the next crisis strikes.

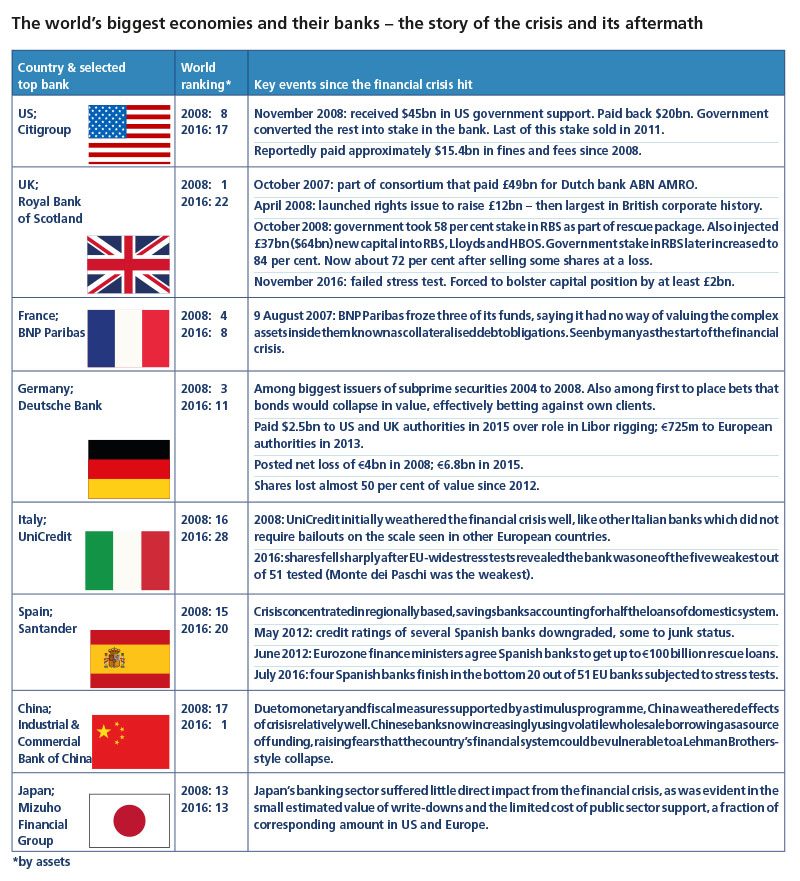

Although it’s been more than eight years since the collapse of Lehman Brothers, the impact of the financial crisis of 2007–8 is still being felt. The apparent failure of governments and regulators to deal with the aftermath of the crisis, or to identify and deal with those responsible, is frequently cited as a major reason for the surprise election of Donald Trump as President of America in November.

Many in the US and elsewhere are still angry that the unethical behaviour and excessive risk-taking in the financial sector, which played such a large part in the crisis, seems to have continued unabated. Wells Fargo was, until recently, the biggest bank in the US by market capitalisation and provides the most recent and dramatic example. In September, it was revealed that bank employees had created over two million unauthorised accounts for customers, from credit cards to current accounts, in a bid to meet their sales targets. Some customers spotted the deception when they were charged unexpected fees, but many went unnoticed, as the accounts were closed soon after being opened.

Following an investigation by regulators, the bank was ordered to pay $185m in fines and penalties. This included a $100m penalty issued by the US Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the largest such penalty the agency has ever imposed. Wells Fargo also has to pay $50m to the City and County of Los Angeles and $35m to the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency.

‘Schemes like this just incentivise people to engage in criminal behaviour,’ says Peder Hammarskiöld, Senior Partner at Hammarskiöld & Co and a member of the IBA Financial Crisis Task Force 2008–2010. ‘Why would anyone want eight accounts? There was no value for the customer – it just artificially enhanced the bank’s share price. As with Enron and the other great scandals, no one seems to have stopped and questioned the reasoning behind it.’

‘This kind of behaviour goes right to the heart of the faith customers have in banks,’ says Hammarskiöld. ‘The bank was actually cheating its customers. No company can ever get away with that and you won’t get bailed out when things go wrong. If you simply do bad business, and you run into a financial crisis, then you can ask your central bank to intervene – but not if you defraud your customers.’

What’s staggering is the number of people who lost their jobs as a result of the scandal. Senator Chris Dodd gave his name to the Dodd-Frank Act, which has been described by the Obama Administration as the most sweeping reform of regulatory legislation since the Great Depression of the 1930s. ‘There were about 5,300, most of them tellers and low-level employees economically. I find it hard to believe that senior management was unaware of this and apparently it goes back to 2011,’ Dodd tells Global Insight.

Two former employees filed a class action in California in September, seeking $2.6bn or more for workers who tried to meet aggressive sales quotas without engaging in fraud and were later demoted, forced to resign or fired.

It’s very surprising that large banks like Wells Fargo and Deutsche Bank can engage in behaviour that damages their own business

Peder Hammarskiöld

Senior Partner, Hammarskiöld & Co and a member of the IBA Financial Crisis Task Force (2008–2010)

Senator Elizabeth Warren was scathing in her assessment of the bank’s conduct at a hearing of the US Senate Banking Committee in September, stating: ‘A cashier who steals a handful of twenties is held accountable, but Wall Street executives almost never hold themselves accountable. Not now and not in 2008 when they crushed the worldwide economy.’

There is now widespread consensus that the only way that financial institutions will change is if executives face jail time when they preside over massive frauds, she added. ‘We need tough new laws to hold corporate executives personally accountable and we need tough prosecutors who have the courage to go after people at the top. Until then, it will be business as usual. And at giant banks like Wells Fargo, that seems to mean cheating as many customers, investors and employees as they possibly can.’

Another big institution in the firing line in 2016 is Deutsche Bank. In September, it emerged that the US Department of Justice (DoJ) had demanded that the bank pay $14bn – not much less than the bank’s market value and more than double its total legal reserves – to settle allegations that it mis-sold mortgage-backed securities in the run-up to the financial crisis. Deutsche says it has no intention of handing over anything like this much, but the news of the DoJ’s demand was enough to cause investors to sell shares in the bank. This reflected fears that Deutsche may have to embark on dilutive capital raising or that it might even need a government rescue. Some see resonances of the Lehman crisis here.

‘It’s very surprising that large banks like Wells Fargo and Deutsche Bank can engage in behaviour that damages their own business,’ says Hammarskiöld. ‘Bank boards and shareholders need to ask why there was not more control over what they are doing. How can you have whole departments running amok with the approval of top management? What happened to the first, second and third lines of defence?’

According to Dodd, there are always going to be institutions where bad or corrupt management will find some way to scam the system. ‘That’s why we have these bodies like the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation and now the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Those are valuable institutions.’

They may be valuable, but none of them were able to spot what was going on at Wells Fargo. Finally, it was uncovered by journalists at the Los Angeles Times.

Does Dodd-Frank have a future?

The Dodd-Frank Act aimed to raise required capital and liquidity levels, reduce leverage and subject banks to ‘stress tests’ to measure their capacity to cope with shocks. It also created the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, one of the bodies that investigated Wells Fargo. Worryingly, Trump said during his campaign that he would repeal the Act, calling it a ‘very negative force’ that had stopped banks lending money to people who need it.

‘President-elect Trump’s transition website promises to “dismantle the Dodd-Frank Act and replace it with new policies to encourage economic growth and job creation”,’ says Randall Guynn, Head of Davis Polk’s Financial Institutions Group and a member of the IBA Financial Crisis Task Force 2008–2010. ‘I believe that Representative Jeb Hensarling’s (R-TX) Financial CHOICE Act, introduced earlier this year, will serve as the starting point for such financial regulatory reform.’

Rep Hensarling is the current Chair of the US House Financial Services Committee. ‘I do not believe that the CHOICE Act will be the end, however, as I expect that the Republican Congress and Trump Administration will have more ambitious plans for changes to the US regulatory framework, and complex negotiations both within the Republican Party and with Democrats will further shape the ultimate result,’ Guynn says.

‘Trump is not the only one to believe that the new rules have not had the desired effect. ‘We find that financial market information provides little support for the view that major institutions are significantly safer than they were before the crisis and some support for the notion that risks have actually increased,’ states Have Big Banks Gotten Safer?, a recent paper by two Harvard academics. One of the authors was Lawrence Summers, who served as President Barack Obama’s National Economic Council Director during the passage of the Dodd-Frank Act.

The Act is at least an attempt to provide a fundamentally coherent framework, Ben Bernanke, former Chair of the US Federal Reserve tells Global Insight. ‘The main elements fit together and most of the key issues are addressed,’ he says. ‘While it is true that the financial system is very complex and the process of implementing the rules has taken a long time, progress has been made. I hope that whatever happens, we don’t forget how serious the crisis was and the tremendous damage it did to the economy.’

According to Guynn, there has been substantial global cooperation and coordination in capital and liquidity regulation, which are the two most important tools for increasing the resiliency of banks against failure (ie, reducing their probability of failure). ‘There has also been substantial cooperation and coordination in improving the resolvability of banks without the need for taxpayer-funded bailouts – ie, reducing the consequences of failure or making them “safe to fail”,’ he says. ‘This has been achieved by requiring banking groups to make their long-term debt subordinate to their short-term; overriding cross-defaults in financial contracts if certain creditor-protection conditions are satisfied; developing new legal tools such as the European Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive; and developing new resolution strategies such as the single-point-of-entry bail-in strategy.’

One key problem is that regulators still lack the resources they need to enforce the rules. ‘Dodd-Frank laid down hundreds of rules and studies and the like, and specified that they should all be completed within a few years,’ Bernanke says. ‘But the law did not include any extra funding for the agencies that had to conduct this work, like the SEC and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC). They’ve had to do this rulemaking on top of their normal enforcement activities, and that’s been difficult.’

Jonathan Wood is a former Chairman of the IBA’s International Sales Committee and is currently a member of the advisory board for the European Regional Forum. He says the burden of regulation is now far heavier than in 2008, but only time will tell whether it has tackled whatever might be the cause of the next crisis. ‘With additional powers, we have seen international regulators flexing their muscles, often working together,’ he says. ‘The regulatory landscape has certainly become more complex and the scale of fines (in particular in relation to foreign exchange and Libor) has led to an exponential growth in the compliance function within banks.’

In the UK, we are waiting to see the full impact of the new Senior Managers and Certification Regime, which came into force in March. This aims to improve accountability and the reputation of banks after a string of scandals, as well as addressing why no head of a bank has been punished as a result of the financial crisis. The most contentious element – a ‘guilty until proven innocent’ provision – was removed at the last minute by the UK government but senior managers and key non-executive directors could face fines or bans from the industry unless they can show they took all reasonable steps to prevent misconduct within their teams. There is also a parallel criminal offence of recklessly mismanaging a financial institution that fails.

Prior to the introduction of the regime, it could be argued that the UK regulator’s attempt to pursue individuals has been less effective. ‘There are questions over whether the right individuals, in terms of their seniority within management structures, have been pursued. Inevitably a change in culture takes time, must take place from the top and must remain a focus for regulators,’ says Wood.

A report published in October by think-tank New City Agenda, endorsed by the Archbishop of Canterbury, offered more trenchant criticism. ‘Financial regulation in the UK operates in cycles,’ it said. ‘Following a crisis, politicians respond to public outrage by introducing new legislation and more detailed regulation. However this new regulation is progressively watered down, not sufficiently enforced or repealed. This lays the foundations for the next crisis.’

While previously this ‘spin cycle’ could take decades, regulators now seem to forget the lessons of the past in a matter of years, the authors add. ‘History teaches us the most crucial thing is not what regulators do directly after the crisis, but how they hold onto the lessons they learned, integrate them into their culture and ensure that this continues to guide their action.’

The EU, like the US, created new regulators in response to the crisis: the European Banking Authority (bank supervision), the European Securities and Markets Authority (capital markets, credit rating agencies and trade repositories) and the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (insurance supervision). They have carried out some useful work, but their continued significance may depend on the outcome of the numerous crises affecting the EU, the most recent of which is the UK’s vote to leave – ‘Brexit’.

‘Now what people are thinking about is Frexit and Nexit,’ says Hammarskiöld. ‘France and the Netherlands leaving are the two biggest dangers to the EU. If one of those or both were to take place, that would probably destroy the Union, and then we will be able to talk about a new financial crisis.’

Culture of irresponsibility

Inadequate responses to banking scandals have helped to perpetuate a perception of impunity. ‘Think of the whistle blower who refused to accept his share of a $16.5m award from the US Securities and Exchange Commission – in protest for the lack of government action against illicit behavior of senior bank executives,’ said Christine Lagarde, Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund, in her keynote address at the opening ceremony of the 2016 IBA Annual Conference in September.

This was a reference to Eric Ben-Artzi, a former Deutsche Bank risk officer, who declined his share of a payout for information that led the SEC to fine the bank $55m last year. The SEC found Deutsche misstated its accounts at the height of the financial crisis by improperly valuing a giant derivatives position.

Ben-Artzi said the fine should be paid by individual executives, not shareholders, and suggested the ‘revolving door’ of senior personnel between the SEC and Germany’s largest bank had played a role in executives going unpunished.

I hope that whatever happens, we don’t forget how serious the crisis was and the tremendous damage it did to the economy

Ben Bernanke

Former Chairman, US Federal Reserve

Elizabeth Warren also highlighted a lack of accountability in the financial sector when questioning John Stumpf, who is now – partly thanks to her vociferous condemnation of his conduct – the former Chief Executive of Wells Fargo. Responding to his claim that he was accountable for the scandal, she said: ‘you haven’t resigned, you haven’t returned a single nickel of your personal earnings, and you haven’t fired a single senior executive. Instead, evidently, your definition of “accountable” is to push the blame to your low-level employees who don’t have the money for a fancy PR firm to defend themselves. It’s gutless leadership.’

When Chris Dodd became Chair of the Senate Banking Committee in 2007, he had an initial meeting with 12-13 financial services institution leaders. During a 90-minute conversation, he said, all they wanted to talk about was executive compensation and the proposed Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. ‘That’s very revealing!’ Dodd tells Global Insight. ‘Given the opportunity to educate a new chairman of the banking committee about what the US needs to do to make the financial system work better, they were only worried about their pay and consumers having a place to get some redress.’

Too big to fail, or too big to litigate against?

If regulation has not been enough to persuade the banks to change their ways, then could litigation play a role? Many are still wondering what happened to the ‘tsunami’ of ‘credit crunch litigation’ forecast by England’s former Lord Chancellor Lord Falconer in 2008. According to Wood, it has been more of a ‘very heavy, prolonged swell’. He says there has been a huge amount of banking and finance related litigation passing through the English courts between 2010 and 2016, but it took time to get going after 2008 as so many litigants were simply in the business of surviving at that point.

The flow of 2008-related claims has abated as the relevant limitation periods have expired, he adds, but market conditions since 2010, combined with regulatory findings, have meant that there is still a steady stream of financial litigation. ‘The prospect of claims relating to the investment banks’ manipulation of foreign exchange markets looms large, particularly in the competition arena,’ Wood says.

Jonathan Kitchin, a partner at Michelmores and a member of the IBA Litigation Committee, agrees that the UK has not seen quite the volume of litigation expected. However, he notes that there have been four or five cases issued in London dealing with how interest and principal under commercial mortgage-backed security structures should be calculated and paid to noteholders. ‘We have also had a Court of Appeal decision on the duty of valuers relating to property used as collateral for securitized loans, while the Financial Conduct Authority’s (FCA) Interest Rate Hedging Product Review and several High Court cases relating to the mis-sale of swaps and hedging has created new precedent in a number of areas,’ he says.

These include the judicial review of decisions by those appointed as a ‘Skilled Person’ by the FCA to look into a firm’s affairs; the enforceability of ‘basis’ clauses governing the relationship between most banks and their customers; and the existence of privilege and the disclosure of documents relating to regulatory investigations into Libor fixing in the US and the UK.

‘New “conflict free” boutiques have emerged, willing to pursue financial institutions, along with litigation funding and associated insurance products, to spot claims, gather claimants and pursue large group actions,’ Kitchin adds.

One of these ‘conflict free’ boutiques is Stewarts Law, which is acting on behalf of a number of institutions in a major compensation claim against Royal Bank of Scotland in the UK’s High Court over its decision to raise £12bn from shareholders in 2008 a few months before it collapsed. ‘The RBS case provides an interesting summary of what came out of the financial crisis and what people expected to come out of it,’ says Clive Zietman, Head of Commercial Litigation at the firm. ‘I thought we would see a re-run of what happened in the late 1980s and early 1990s, which was a raft of fraud scandals like Guinness, Blue Arrow and Barlow Clowes. In fact, the scandals that emerged were so huge that they were almost too big to handle.’

This kind of litigation in England is not for the faint-hearted. ‘You need a lot of money,’ admits Zietman. ‘RBS’s costs in this case are already over £100m, and we haven’t even got to the trial yet. This is why we haven’t seen as much litigation as expected. It’s scary. It takes masses of time, money and expertise to bring these cases and to bring them all together into a system that doesn’t really lend itself to class actions at all.’

The scandals that emerged were so huge that they were almost too big to handle. RBS’s costs are already over £100m and we haven’t even got to trial yet

Clive Zietman

Partner, Stewarts Law

In the US, by contrast, shareholders have much stronger rights for suing. ‘You have juries, you don’t have costs orders, you don’t have adverse costs, you have a whole class action system that we don’t have in England,’ says Zietman. ‘It’s much more difficult here for anyone to bring a claim of this kind.’

Like Ben Bernanke in the US, Zietman highlights a lack of regulatory resources in the UK as one of the main factors working in the banks’ favour. ‘Look at the Serious Fraud Office (SFO),’ he says. ‘Has it actually got the resource, the expertise and the quality people to prosecute on the back of any new legislation? It’s all very well passing new laws, but you’ve got to follow through on it.’

Hammarskiöld agrees. ‘It’s very complicated, and you need highly skilled lawyers and professionals to convict people who commit serious fraud,’ he says. ‘Governments need to invest much more in order to get on top of that.’ As far back as the 1990s, the SFO couldn’t even convict anyone after Robert Maxwell was found to have stolen millions of pounds from a company pension scheme.

The tsunami hits Europe

In other countries, the amount of litigation to emerge since the financial crisis is viewed differently. ‘In Austria we do have a tsunami,’ says Bettina Knoetzl, a partner at Austrian law firm Knoetzl and Co-Chair of the IBA Litigation Committee. ‘We do not know how to cope with this because we do not have an instrument of collective redress and not every lawyer joins the claims into one lawsuit, so there are really more than 10,000 currently pending.’

Some of these claims have their origins in late 2007, while many are related to small investors. On the whole, these are people who were incentivised to make investments by commercial or independent financial advisors before the advent of the crisis. ‘In some cases, criminal proceedings are pending in parallel, so these claimants have two interests in the proceedings,’ Knoetzl says.

Some claims concluded in a mass settlement. The best known of these is probably Immofinanz, the Austrian property group that agreed in November 2015 to pay more than €60m to thousands of investors who started legal proceedings in 2008 seeking €240m. They had accused the firm of withholding market-relevant information.

One interesting aspect of financial crisis litigation is the extent to which losses were incurred due to bad management rather than a global crisis that was beyond the control of the financial institution concerned. ‘Some investors have claimed there was fraudulent management or criminal activity, but the defendants say problems arose because of the impact of the financial crisis and the real estate crisis both together,’ Knoetzl says. ‘They present this as a typical market risk.’

In the absence of any formal mechanism to settle class actions, the Austrian courts have made several attempts to deal with the avalanche of cases, says Florian Kremslehner, a partner at Dorda Brugger Jordis and former Co-Chair of the IBA Litigation Committee. ‘Most recently, the appellate courts and the Supreme Court have developed a concept that facilitates the use of evidence found in other “mass claims” cases and to treat relevant facts as “notorious”,’ he says. Austria’s Ministry of Justice has also set up a working group to discuss proposals on how to take evidence in mass claims more efficiently.

‘Sooner or later, Europe will probably recognise that having some sort of collective settlement tool available – like in the Netherlands – will be a good thing not just for claimants but also for companies facing these claims,’ adds Knoetzl.

Marcin Radwan-Röhrenschef, a partner at Polish law firm Röhrenschef and former Membership Officer of the IBA Litigation Committee, says that in Poland, post-crisis litigation can be split into two main groups. The first consists of companies suing banks for losses on foreign exchange options (mainly on yen). This might have been for an allegedly unjustified refusal to close their position on 18–19 September 2008 or for providing misleading information when entering the transaction.

The other group consists of claims related to mortgages taken out in Swiss francs. Like many citizens in central Europe, Poles flocked to accept offers to borrow in the Swiss currency before the financial crisis so they could benefit from lower interest rates. The halving of the Polish zloty against the franc in the past six years has left many of the 565,000 Polish borrowers struggling to service loans now worth more than their property. ‘The plaintiffs challenged the bank spreads, the misleading information about forex risks and the fictional nature of the contracts (the loan was in fact paid in Polish zlotys),’ says Radwan-Röhrenschef. ‘Some of the claims have been successful, while some are still pending.’

In Japan, there was no obvious spike in civil litigation cases after 2009, notes Osamu Inoue, a partner at Ushijima & Partners and a member of the IBA Litigation Committee. ‘Some news of litigation related to the financial crisis brought by universities, including Komazawa University and Osaka Sangyo University, against financial institutions has been reported,’ says Inoue. ‘The reason why this news attracted attention may be partially because these investments were against the “public interest” of Japan.’

However, other kinds of public utility corporations that were reported to have suffered losses after the financial crisis tended not to bring lawsuits, he adds. ‘One reason may be that they feared that someone inside the organisation might be accused of being responsible, or some other internal corporate discord might result.’

Much of the high profile litigation regarding Japanese companies may have been subject to US or UK law, according to the choice of law clause of the relevant contracts. For example, when Lehman Brothers Holdings sued Daiwa Securities Capital Markets Co, claiming that the Japanese investment bank shortchanged Lehman in derivatives trading to the tune of $75m at the time of the latter’s bankruptcy in 2008, it did so in the US.

The clock is ticking

‘Unless we change the culture of regulators we will be sleep walking into the next financial crisis,’ says the New City Agenda report. ‘Memories of the 2008 crisis are rapidly fading and industry lobbying has become more intense. There is a clear and present danger that we will repeat the mistakes of history. Much needed change is already being watered down. The attention of politicians has moved on.’

John Lanchester, the author of Whoops!, a layman’s guide to the financial crisis, used even stronger words in 2013. In their current condition, British banks are ‘an existential threat to British democracy, a more serious one than terrorism, either external or internal,’ he said.

These comments relate to the UK but they reflect global unease about our apparent failure to address the root causes of the financial crisis. Banks may no longer be ‘too big to fail’ in the way they were, but they still seem to be too big to be dealt with in any meaningful way. If their response to scandal is simply to pay a fine and return to what Elizabeth Warren and others refer to as ‘business as usual,’ then there can be little doubt that another crisis is not far off. If something significant is not done soon, the consequences could, as Lanchester suggests, be even more profound. Yet again, the banks, and those that run them, will almost certainly get away with it.

Jonathan Watson is a journalist specialising in European business, legal and regulatory developments. He can be contacted by email at jonathan.watson@yahoo.co.uk