Global leaders: Martyn Day

Thursday 9 April 2020

Founded to act for the most vulnerable in the UK and internationally, Leigh Day is among the foremost law firms focused on business and human rights. Martyn and his firm have always relished battling powerful corporations and governments. He talks to Polly Botsford about representing Iraqis in claims against the British army, being investigated by the Solicitors Regulation Authority and hitting the headlines.

Polly Botsford: The list of corporations that you have crossed include Trafigura and Shell. I remember very particularly the Shell case where you represented the Bodo community in Nigeria. They were fishermen in the mangrove creeks, and the area was polluted from oil spills. Shell settled for £55m and promised to clean up the area. But there must be so many of those cases. Can you think of one that you feel has made a real difference to people’s lives?

Martyn Day: Bodo was a big, big case. I went back there about a year after the case finished and it was lovely to see the amount of new buildings. As far as I could tell, most of the money was spent on trying to improve the quality of lives. They were spending their money on education for their kids. You just felt that the community was significantly improved by that, so I felt very proud of that.

Mr Justice Leggatt at one stage said, well actually access to justice in Iraq, in terms of bringing cases about what the British did, was basically access to Leigh Day

PB: What’s it like to bring a case like that? How do you choose which case you take on? How do you cope with the responsibility and the pressure?

MD: A number of different things. For me, I tend to never take the same case twice. I’ve got a very low boredom threshold, so I pass to others any kind of case I’ve done before. I like to take on a case that looks difficult. Obviously, we’ve got to think we’re going to win. It’s rare that you’re thinking, there is a definite 90 per cent chance you’re going to win, but we wouldn’t take on a case that was really hopeless. There are certainly some very tough ones. We took on the Mau Mau case, which was about Kenyan freedom fighters from the 1950s. After they came to me and I came back with a case, I met with a number of QCs – left-wing QCs, human rights QCs – and they nearly all turned me down. In fact, the one who was prepared to say yes was Keir Starmer. So that was a case where we actually thought the chances were pretty slim, but I just felt we had to do it. I thought morally we had to do it, so the firm backed me up – thank goodness they did. But mostly I like to take on the big giants of British multinationals. I like to act for people who are in a powerless state, who could otherwise not get justice. So, balancing all those things together, the cases come in.

PB: But it’s not that the fight is more important than the reason?

MD: No. You know, in the end, I’m just a lawyer. I’m there to represent the interests of the clients. It’s not my fight. It’s their fight. I want to put my firm at their disposal, but it’s their fight. And it’s always crucial that you don’t ever lose sight of that.

PB: Do you have a prima facie position that most governments and corporations are pretty suspicious?

MD: Well, I am clear that all corporations are driven by profit. That’s their goal anyway, it’s not anything surprising. The fact that they are there to make profit is such an overwhelming factor. They put out statements about their corporate social responsibility and you realise when it comes to it, it means very little. On the ground, whether you’re in Nigeria or out in other parts of Africa, in South America, the Indian subcontinent, that when they’re far away from the prying eye of the media, they just get on and ride roughshod on local people’s rights in many, many instances. For me, holding them to account is quite a critical feature of our society. I think that’s also true of British government. You know, the terrible things that they did in Iraq, the terrible things they’ve done in Afghanistan, all lies in a pattern – you look at what happened in Northern Ireland, and, previously before that, what happened in places like Kenya with the Mau Mau – they’ve often left a legacy in parts of the world that we will never actually recover from. We want to study it and, in some way, provide justice for those people.

Martyn Day with Mau Mau veteran clients outside the Royal Courts of Justice, London, 2011/ Daniel Hughes

PB: On that point, let’s talk about the Iraq war and recap on what the claims were, specifically. The claims arose out of an ambush by an insurgent group, the Mahdi Army. British soldiers engaged in the battle, which was subsequently referred to as ‘Danny Boy’, and a number of Iraqis were killed. Out of that came claims against the Ministry of Defence (MOD) by your firm and Phil Shiner’s firm, Public Interest Lawyers, known as the Al-Sweady claims. These claims detailed that Iraqis were tortured – and I’m simplifying and summarising – by British soldiers. Alongside that, we also had the Iraq Historic Allegations Team, two government public inquiries and a huge number of claims against the MOD. I suppose what happened for you personally, and for Leigh Day, was that your decision to represent these detainees resulted in vilification. You’ve been described by the press as unscrupulous. When I had a look at your website, I did notice that those claims weren’t something that’s highlighted in your profile. That’s not because you regret bringing those claims, is it?

MD: Not for a single second. In the end, there was a judge in charge of these cases, all the individual complaints, called Leggatt. Mr Justice Leggatt at one stage said, well actually access to justice in Iraq, in terms of bringing cases about what the British did, was basically access to Leigh Day. Because we were the only firm who was prepared to get out there and do these cases. You recognise that bringing these sorts of cases are going to bring the might of the Daily Mail and The Sun, as well as the Conservative government, against you.

PB: How do you feel when you read the media coverage?

MD: Well, I’m not that worried personally. But I know for the firm – for the staff who go home to their mums and dads who read The Sun and the Daily Mail and who think ‘oh my God, what’s the firm up to’, it’s a concern. You want your staff to feel proud about what they do, so it’s not always easy. But the battle is there to be fought. There were undoubtedly mistakes that we made along the way. That would be true in any case that we do – probably that anybody ever does. Fundamentally it was right. And holding the British army to account, holding the military generally to account, is absolutely crucial if we are to have a free society because, in the end, their nature is to cover things up.

PB: But can you understand that people think, these are brave soldiers and they’re putting their lives at risk: it’s all the fog of war. And then for these soldiers to have to face what could be devastating consequences of legal action ten years down the line; can you understand people’s anger about that? Johnny Mercer MP said you destroyed British soldiers’ lives. Can you understand why he thinks that, even if you don’t agree?

Holding the British army to account, holding the military generally to account, is absolutely crucial if we are to have a free society

MD: It is very important that it’s clear that we never bring cases to do with what happens in the battle itself. The courts have made it absolutely clear – and quite rightly, I’ve got no objection at all – that in the middle of a battle, you cannot expect soldiers to be thinking ‘what does the Human Rights Act say about this?’ and I totally accept that. The only case we’ve actually brought was on behalf of British soldiers’ families, where soldiers were being sent into battle without the proper equipment. That’s obviously very different to what we’re talking about here in terms of Iraqi claims. The Iraqi claims are about what happens once the battle is finished and how the British military then treat the people being detained.

PB: But if there’s an ambush wouldn’t that count as a battle scene?

MD: There’s been the odd case where terrible things have happened – whether it’s an ambush or whether you’ve got a soldier who has gone berserk and started to shoot at people. But in terms of a proper battle, where things are properly done, then there is no reason for soldiers to have to worry. It is what happens once the people are in their custody, that is the crucial question. Any modern soldier in our army has got to accept that once you are in control of somebody, they have human rights, they have the right to be treated in a respectful manner. What is the purpose of us going to war in Iraq, or whatever, if it isn’t to bring about justice, human rights and democracy? That’s for us to then impinge on them to say, look, this is what is right.

PB: Setting an example?

MD: Absolutely, because otherwise what’s it all about? Why are we risking our people’s lives if that is not the ultimate goal? Once you pass the fog of war and have got people into custody, we need to recognise that we killed Baha Mousa, that we’ve delivered, time after time, abuse, and beatings. It is something we’ve got to learn from. We need to understand it, to move on, to make sure it doesn’t happen again.

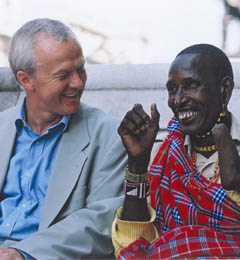

Martyn Day and Kipise Louroilkeek, a Kenyan Leigh Day represented who had been injured as a result of British army live weaponry, left over from practice manoeuvers in Kenyan fields, in 2002/ Leigh Day

PB: Michael Fallon stepped in as Defence Secretary and reported your firm to the regulator, the Solicitors Regulation Authority (SRA), saying you had committed professional misconduct for the way that these claims were handled. There were 19 allegations, including of misconduct as a solicitor; financial payments to fixers; this Office of the Martyr Al Sadr detainee list, which connected the detainees to the Mahdi Army and which was only disclosed much later on, and was considered a key document by the MOD; and a press conference where the SRA claimed that you and the firm made allegations about the British soldiers, which were misleading and unprofessional. You were cleared of all allegations. But what was it like to be in a seven-week trial? To be on the receiving end of some of that scrutiny that you’ve carried out on others?

MD: It was tough, but it was fascinating. What was most interesting for me as a lawyer was that you’re suddenly in a position where you have to go back over about ten years of your life, that you realise you’ve just totally forgotten. And, having to go back over it, to reconstruct in your mind, through all the emails or the letters and everything else, then suddenly you start to piece it all together. It was very interesting for me in terms of what I now say to people who are under cross-examination, having had to go through that myself. And say, look, you’ve got to be as prepared as the QC, you’ve got to put as much time as the QC will in to attack you, you’ve got to make sure you defend.

Do not go in there assuming that it will all come back to you, you’ve really got to go through every single letter, every email, just to remind yourself what had actually happened. So that was a massive lesson for me. But I think most importantly for me was that, initially, when the complaints came in, you immediately think ‘oh my God! I’m on the end of one of the most enormous muck-ups here.’ Then when I had a chance to go through it all, increasingly I felt, no I’ve made the odd mistake, but they were just normal mistakes that you make – decisions you make at the time with good intentions, but you realise later on that they were not good decisions. But that’s very different to misconduct. There wasn’t a single thing that I felt we’d done wrong. Once I was clear about that, I felt fine in myself.

The terrible things that they did in Iraq, the terrible things they’ve done in Afghanistan, what happened in places like Kenya with the Mau Mau - they’ve often left a legacy in parts of the world that we will never actually recover from

PB: Going back to the point about prosecuting soldiers more generally, we have a consultation document on UK legislation here, on when and how you can prosecute British soldiers. Do you agree that’s the way to go? Do you feel there were some lessons learned in terms of how you brought those claims and that this is actually a good response to that?

MD: I think two or three things. First, in the aftermath of a war there needs to immediately be an independent investigative team. I think a lot of what Johnny Mercer very fairly says is that this grief has carried on for 17 years after the events. And I can totally relate to how tough it must be for the soldiers. So I think it has to be an independent force, that will comply with what the courts say and that they come in quickly and deal with it with speed. Second, I totally agree that for minor assaults, which we saw tons of, ten to 15 years after the event, they shouldn’t have happened, but the idea we are still trying to investigate things of that minor nature, it’s not realistic. Again, in terms of the balance of society and resources, that is wrong. I totally agree that there should be some sort of an amnesty for these things. However, when you get to murders, when you get to rape, when you get to very serious assaults, there can’t be any sort of amnesty for those people.

PB: You wouldn’t agree that there should be some kind of time limit?

MD: Absolutely not. We’re seeing all these sexual assault and abuse cases going on that are important to society, which are 30, 40, 50 years old. The idea that a soldier, acting on behalf of the Crown, of the government, that we can say, look, they’ve killed somebody but actually ten years later, well, we’re going to just push that all under the table. That’s total nonsense to me; murder is murder. If the evidence is there then it is there, even if it all comes 30, 40, 50 years later. In society generally, but in terms of the military just as much, then for me, there can be no amnesty.

PB: So, what’s next for Leigh Day? For Martyn Day?

MD: Since we had the initial hearing for the SRA in 2017 and the appeal in 2018, we’ve had about 18 months that we’ve been able to put that to one side and just get cracking on. We’ve got the Vedanta case, which we were in the Supreme Court about in early 2019, where we were challenging in terms of jurisdiction. A big part of what we do is we bring the cases here in London against the parent company where the subsidiary of the parent is operating in the developing world. And, if we’d have lost that, that would have been a real problem for us.

PB: And the reason you do that is that actually in the end, it’s much better if it’s heard in London because the system works.

MD: In some ways it would be ideal for it to run in the home country because the community that’s been affected, local lawyers, local language, media, they would understand it all a lot better. But the difficulty is for most developing world countries, they simply haven’t got the wherewithal. They’ve got no legal aid, so the only way that lawyers can act is if the clients pay for them. These are nearly always clients who haven’t got the money. So this is the only way to get access to justice for many developing world countries against these big cases, where you’re taking on a multinational of the sorts Shell or BP.

PB: Part of me thinks what we’re talking about is capacity building. Wouldn’t it be better if your energies were spent helping these countries develop some kind of internal rule of law?

Any modern soldier in our army has got to accept that once you are in control of somebody, they have human rights, they have the right to be treated in a respectful manner

MD: We brought a case, about 20 years ago now, in London against a company based in South Africa, Cape Asbestos. We brought this case against their parent company here, but they had a subsidiary over there in South Africa. So, we brought the case in London, again the courts didn’t provide access to justice in South Africa as they don’t have the infrastructure. As a result of that case, very largely, they have since brought in class action claims that you can do on a ‘no win, no fee’ basis. So, now, we would never run the case here. We have helped in bringing cases in South Africa for that very reason. Now, South Africa’s the wealthiest of all the African countries and so they had that benefit. Other countries are starting to look more at this. In Zambia, I understand, in the last few months since our win on the Vedanta case, lawyers have been trying to say, well, look, can we press our government to bring in class action status and that sort of thing. We are very unusual. There are not many Leigh Days around, not just in this country but internationally. I feel our primary role is to be out there, bringing these cases to the attention of the world through the media here in the UK. People will see what’s going on and then hopefully lessons will be learned to actually encourage local societies to take up the sort of law that we have in the UK, or the US, or Canada, wherever, and allow these cases to be brought locally.