The pardon: politics or mercy?

Anne McMillan

The pardon exists in many countries around the world, regardless of political systems or religious ideologies. However, its use has the power to ignite controversy, not least because some view it as an outdated, archaic power.

Recently, the President of the United States, Donald Trump, shone a spotlight on a long-running legal debate when he tweeted about his potential to pardon himself: ‘As has been stated by numerous legal scholars, I have the absolute right to PARDON myself, but why would I do that when I have done nothing wrong?’ [sic].

Whether these assertions turn out to be true or not, President Trump identified the key elements of the pardon: it is usually issued by a head of state or government and traditionally implies an admission of guilt on the part of the beneficiary. Legally, and more specifically, it is the executive power to forgive a crime.

The gift of kings

The pardon flourished in medieval Europe as a tool of the monarch, though even by that time it had enjoyed a lengthy history, including use in antiquity by the Greeks. During the 18th century, the Royal prerogative of mercy was used to fill gaps in the legal system (such as the absence of a defence of insanity), as well as being an important instrument in the pacification of civil strife. As Justice Robert Sharpe, a judge of the Court of Appeal for Ontario, says: ‘the traditional view was that pardons were a safety valve that allowed for consideration of mercy and compassion in cases where the law failed to reflect understandable human frailties and where it would be dangerous or inappropriate for the law do to so formally.’

By the time of the Enlightenment, though, pardons were also viewed by some commentators as an arbitrary, monarchical power. ‘In democracies, this power of pardon can never subsist,’ pronounced English jurist, William Blackstone, author of a seminal 18th-century work on English common law. Yet subsist it did. The US Supreme Court, in the 1927 case of Biddle v Perovich, said that ‘[a] pardon in our days is not a private act of grace from an individual happening to possess power. It is part of the Constitutional scheme.’ But, almost a century later, does this still hold true?

Modern use

The use of a pardon in the 21st century takes many forms to achieve various goals. So, who in the modern world has the power to offer this unique form of mercy, this ‘act of grace’?

Although in some jurisdictions the legislature may hold the power of pardon, pardons are often issued by the head of state, who may be required to consult (though not always follow) the advice of others, such as a justice minister, a pardon office, the legislature, the judiciary – or nobody.

Regardless of who grants a pardon, it can do various things for individuals and groups, both living and dead. It may be used to right a historical wrong, clear a criminal record or reduce a sentence. In some countries, its primary role has been to commute the death penalty, often when its abolition is a politically sensitive issue. More controversially, a pardon might also pre-empt any formal finding of guilt by being applied before, or even during, legal proceedings.

Usage and abusage

To pardon a historical wrong is possibly the most clear-cut and least controversial use of the power. Matthew Reinhard, former Co-Chair of the IBA Criminal Law Committee, says that although ‘the power can certainly be abused, it can also be properly invoked to address prior injustices that, as society advances, seem inherently unfair’.

For example, British soldiers who were shot for desertion during the First World War were finally pardoned by statute in 2006. One of those was Private Harry Farr, who served two years in a brutal war before reaching breaking point. He was sentenced to death for cowardice at the age of 25 after a 20-minute hearing where he represented himself. The granting of a pardon in ‘deserter’ cases like these, now that post-traumatic stress disorder among soldiers is commonly recognised, seems relatively uncontroversial. Even so, a pardon for these men was refused in 1998 by the United Kingdom defence secretary at the time.

A more recent case was the posthumous pardon granted in 2018 by President Trump to Jack Johnson, the black boxer who was convicted more than a century ago under the White Slave Traffic Act after crossing a state line with his white girlfriend. Trump said the pardon was granted because of ‘what many view as racially motivated injustice’.

Pardons were a safety valve that allowed for consideration of mercy and compassion in cases where the law failed to reflect understandable human frailties

Justice Robert Sharpe

Judge of the Court of Appeal for Ontario

Yet Johnson had previously been refused a pardon by both Presidents Bush and Obama. The reasons for the refusals are complex, but among them it seems that Trump’s predecessors followed the advice of the US Office of the Pardon Attorney, a practice which is normal, though not obligatory, for presidents. Trump, who apparently had Johnson’s case brought to his attention by actor Sylvester Stallone, broke with tradition by not seeking the advice of the Office.

If the Johnson case seems to be an argument for maintaining maximum flexibility in issuing pardons, what also emerges from it is the sense that pardons can frequently be granted arbitrarily. While the Johnson case may not be too contentious, other individual pardons given by President Trump have attracted accusations of bias, though he is not the first president to attract such criticism. One of the more notorious examples was President Clinton’s pardoning of his brother for earlier drug offences.

Thus there is privilege in pardons, which threatens to undermine the principle of equality before the law and perhaps also calls into question common notions of justice. Richard Goldstone, previously a South African Constitutional Court judge and former Chief Prosecutor at the International Criminal Tribunals for both Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia, thinks it may be time to curtail the use of pardons.

‘In my view, the pardon power is inconsistent with the rule of law and allows the head of state to exercise an arbitrary power,’ he says. ‘Where it is subject to judicial review the position is somewhat ameliorated but by no means completely. I have no doubt that the power can be replaced with a more democratic system. Some process is necessary to deal with injustices or changes in the relevant societal norms.’

The 1993 case of a Canadian father who was convicted of second-degree murder for killing his severely disabled daughter serves as a microcosm of many of the potential problems of the pardon (See box: The Latimer case). A brief reading of the case will show that refusing someone a pardon can be as divisive as granting one. This may be especially true when pardons are given for political reasons.

Politics and pardons

It is not unusual for pardons to be granted in the interests of the future good of a nation, especially one recovering from internal strife, such as Lebanon or South Africa. Collective pardons (or amnesties) may be extended to those committing crimes in a national conflict. These types of pardons are considered more acceptable when granted within a transparent, legal framework, such as a truth commission requiring an admission of guilt. In such cases, the peace and stability of the country are judged to be of greater public benefit than the punishment of an individual.

‘Pardons have a role to play in avoiding legal proceedings where they would be clearly contrary to the public interest or the promotion of some important public purpose, such as reconciliation after a traumatic or catastrophic event,’ says Sharpe.

Pardons may also be used to pre-empt conflict by dissipating tensions within a society. In early 2018, the President of Egypt issued a pardon via Twitter to over 300 people, many of whom were arrested for taking part in ‘unauthorised protests’ against the government. In another instance, on assuming the throne in 2016, the King of Thailand pardoned up to 150,000 prisoners by either shortening their sentences or sanctioning their immediate release, including those jailed for insulting the royal family.

In my view, the pardon power is inconsistent with the rule of law and allows the head of state to exercise an arbitrary power

Richard Goldstone

Former South African Constitutional Court judge

While there may be some consensus about pardons designed to protect the nation from further conflict and division, politically motivated pardons of living individuals, on the other hand, are often accompanied by the odour of corruption and suspicions of personal bias. In 2017, the Polish President pardoned the former head of the anti-corruption agency in the middle of a legal proceeding against him, but there was little that sceptics or opponents of the pardon could do. The country’s Constitutional Court declared: ‘The pardon is the prerogative of the president and the president does not have to consult with anyone...’

Nevertheless, pardoning an individual before a conviction, though it may be legal, seems more like a subversion of justice. ‘The danger lies where the head of state begins utilising the pardon to pre-empt or interfere with investigative and law enforcement processes,’ Reinhard says. ‘It is difficult for me to conceive of a “democratic” pardon power that could be fairly applied without discrimination.’ Such pardons may ultimately undermine public confidence in the justice system.

The Latimer case

Robert Latimer’s daughter Tracy was born with brain damage and never progressed beyond a mental age of five months in her 12 years of life. She could not talk, suffered multiple seizures daily, had been in persistent pain and endured many operations. Tracy’s condition prevented the use of strong pain killers. Faced with yet another operation, which would lead to more suffering, Latimer decided continuing Tracy’s life was tantamount to torture and decided to end it.

He was sentenced to life in prison, the mandatory minimum for second-degree murder. In 2010, he was released on full parole, having served the minimum of ten years. The Canadian Supreme Court gestured in the direction of the Royal prerogative of mercy in its 2001 decision in Latimer, while being careful to distance itself from any potential pardon decision:

‘Where the courts are unable to provide an appropriate remedy in cases that the executive sees as unjust imprisonment, the executive is permitted to dispense “mercy”, and order the release of the offender.

‘But the prerogative is a matter for the executive, not the courts... Mr. Latimer has undergone two trials and two appeals to the Court of Appeal for Saskatchewan and this Court, with attendant publicity and consequential agony for him and his family.’

Latimer had been shown ‘mercy’, but he had not been pardoned or forgiven. His lawyer has recently applied for a pardon, arguing that the fear of political consequences was an influential factor in his client remaining un-pardoned: ’Power is so often subjugated by responsibility, the intricate web of foreseeable consequences and fear of the unpredictable.’

But even now politicians appear stymied by the case, possibly because of continuing forceful lobbying by some anti-euthanasia and disabled lobby groups, such as the Canadian Association for Community Living, which stated that ‘a pardon for Mr. Latimer would be a direct injustice to Tracy and her legacy and perpetuate society’s stigmatization against persons who have disabilities’.

It could be argued that a pardon for Latimer would be socially divisive, not unifying. Perhaps it only appears that way because some groups are more vocal than others and therefore able to generate political pressure. An opinion poll of Canadians in 1999 found that 73 per cent believed Latimer ended his daughter’s life out of compassion and should receive a more lenient sentence, but the law provided no such option. The only option was a pardon, but the Canadian government so far remains silent.

But even in a democratic system, judicial involvement in overseeing the use of a pardon is no guarantee of transparency or fairness, as Goldstone observes: ‘Judicial review of the pardon power is difficult in most cases,’ he says. ‘How does the objector establish bias or improper motive? It can be done but in most cases it is not likely to succeed.’

Thus, we are left with the notion that pardons are inherently vulnerable to political influence and vested interests. The satirist Ambrose Bierce defined ‘pardon’ a hundred years ago as being ‘to remit a penalty and restore to the life of crime’.

Pragmatic pardons

Perhaps one of the less controversial uses of pardons is to ease burdens on state administration and infrastructure, such as pardoning classes of convicted prisoners or people yet to be charged in order to reduce overcrowding in jails or cut a backlog of arrest warrants. Such pardons may provide a solution (albeit probably short-term) to a creaking justice system, while offering some temporary relief to aggrieved citizens.

Yet even these pardons may court dissension. For instance, in 2013, the retiring Czech President Václav Klaus marked 20 years of independence for the Czech Republic by pardoning over 6,000 detainees, nearly a third of the prison population. But soon a significant proportion of these prisoners had re-offended and were back in jail. This pardon also controversially included a group of high-profile individuals being investigated for corruption and fraud. President Klaus, wary of accusations of bias, protested ‘I did not have a single specific person in front of my eyes when [preparing] the amnesty.’ That may or may not be so, but it raises the question of whether such widespread pardons really constitute an effective aid to rehabilitation of prisoners or can be a substitute for a proper parole system.

The power can certainly be abused, it can also be properly invoked to address prior injustices that, as society advances, seem inherently unfair

Matthew Reinhard

Co-Chair, IBA Criminal Law Committee

The answer is ‘probably not’, but even in countries with weak legal systems or autocratic leaders there often exists some self-limiting mechanism in the use of pardons. In those places, it is still noticeable that public security factors are considered and that pardons are often offered to those serving shorter jail sentences for non-violent or ‘social’ offences (such as drug-related crimes). Offences such as terrorism, murder and rape are frequently, though not always, excluded. Group pardons are also commonly given for humanitarian reasons, such as the age or illness of prisoners. But always there is the question of whether such pardons are free of political motivation to increase the popularity of governments or a head of state with a particular constituency.

US Presidential pardons – a history of reprieve

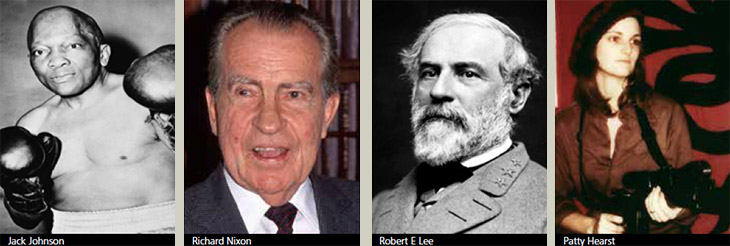

President Trump’s historical pardon last year of Jack Johnson, the first African American world heavyweight boxing champion, is one of the latest examples of a discretionary executive power used by virtually every US president to date. More than 20,000 pardons and commutations have been issued by US presidents in the 20th century alone.

President Trump granted Johnson a posthumous pardon for what he called ‘a racially motivated injustice’, when the boxer was convicted in 1913 for crossing state lines with his white girlfriend.

One of the most controversial was President Gerald Ford’s 1974 pardon of his predecessor Richard Nixon, for his involvement in the Watergate scandal. Ford said the unconditional pardon was in the best interests of the country. It ended any possibility of Nixon being indicted. Ford also pardoned Robert E Lee – the Confederate General’s full rights of citizenship were posthumously restored in 1975 following a five-year congressional effort.

President Clinton granted a pardon to Patty Hearst in 2001, following one of the more bizarre cases in recent US history. The granddaughter of American publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst was convicted of bank robbery in 1976 after being kidnapped and allegedly brainwashed.

The quality of mercy

Francis Bacon wrote several centuries ago that ‘in taking revenge, a man is but even with his enemy, but in passing it over, he is superior; for it is a prince’s part to pardon’. His words hark back to the origin of the pardon: the gift of a monarch ruling by divine right. But can, or should, current-day politicians try to act as unbiased, god-like arbiters? Sharpe points to the inherent contradiction that the flexible nature of the pardon power, which makes it so useful, can also lead to arbitrary consequences: ‘In most countries we have formalised the process,’ he says. ‘I think this may be because the political actors no longer want to take responsibility for such decisions. The more formalised and legal it becomes, the less capable it is to discharge the original purpose.’

Adding more checks to the power of the pardon to meet modern ideals of transparency and the principles of a liberal democracy is worth considering, especially in a country where the rule of law is strong. On the other hand, in less democratic systems it may hamstring the pardon when it serves to mitigate some of the otherwise harsh effects of a weak legal system.

Goldstone points to the advantages of situating a pardon power within a well regulated administrative structure. ‘A legislatively appointed body could be made subject to rules that set out criteria and requirements for the exercise of the modern pardon power,’ he suggests. ‘It would be less flexible but that is the price for transparency and fairness.’

Ultimately, regardless of geography or politics, as criminals languish in prison for many years after their convictions, something in human nature suggests a need to move on. Now, as in centuries past, punishing criminals may demand more nuanced answers than rigid laws can supply. It is notable that the 1990 UN Standard Minimum Rules for Non-custodial Measures demand that all of the five post-sentencing alternatives to facilitate reintegration of offenders be made ‘subject to review by a judicial or other competent independent authority’ – except the pardon.

Thus, in an imperfect world, politics and personal bias will still play a role in the dispensation of this particular form of mercy. And, in such a world, it may be the Robert Latimers who will continue to pay the price for its deficiencies.

Anne McMillan is a freelance writer. She can be contacted at mcmillan.ae@gmail.com