Have we reached peak globalisation?

Jonathan Watson

Protectionism is on the rise and assumptions underpinning decades of international cooperation and trade are being called into question. Global Insight assesses whether globalisation has had its day – and, if so, what might be next.

Globalisation is going through ‘a major crisis,’ said French President Emmanuel Macron when he addressed the World Economic Forum in Davos at the start of 2018. ‘Regarding trade, we are going back to strategies that are not cooperative, towards protectionism, towards breaking up what the WTO has done and threatening certain regional agreements, and we are unravelling what globalisation has accomplished.’

It was an alarming assessment, no doubt inspired, at least in part, by the election of the avowedly protectionist Donald Trump as United States president in 2016. Trump appears to be the first president in more than 80 years to oppose the expansion of trade. During his first year in office, he withdrew the US from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a trade pact involving 12 (now 11) countries on both sides of the Pacific Ocean; launched moves to renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with Canada and Mexico; and threatened to impose barriers against imports from China.

Most recently, in March, President Trump announced that America would impose a 25 per cent tariff on steel and a ten per cent tariff on aluminium in an effort to force other countries into ‘fairer’ trade agreements. ‘Trade wars are good, and easy to win,’ he claimed. China responded by saying the tariffs ‘seriously undermine’ the global trading system and raised the possibility of retaliatory measures against US goods such as pork, apples and steel pipe.

According to trade credit insurer Euler Hermes, there were 467 protectionist measures implemented worldwide in 2017, with the US responsible for 90 of them. The Trump administration implemented 30 new import tariff measures, 20 anti-dumping measures and 17 tariffs on China alone, with the headline tariff being the 30 per cent import tariff on Chinese solar panels.

These measures reflect widespread anxieties. ‘Many citizens consider that globalisation directly threatens their identities and traditions to the detriment of cultural diversity and their ways of living,’ noted Harnessing Globalisation, a ‘reflection paper’ published by the European Commission (EC) in 2017. ‘Citizens are anxious about not being able to control their future and feel that their children’s prospects will be worse than their own. This is due to the view that governments are no longer in control or are not able or not willing to shape globalisation and manage its impacts in a way that benefits all.’

Some have drawn comparisons with the years between 1860 and 1914, a phase of economic development characterised by the expansion of transport and communications networks, significant growth in international trade and a huge flow of capital. The Austrian political economist Karl Polanyi once argued that the social crises of the first half of the 20th century had their origins in poorly conceived attempts to liberalise and globalise markets – a parallel that has not escaped the attention of those studying the populist anti-globalisation movements of today.

Barriers to trade

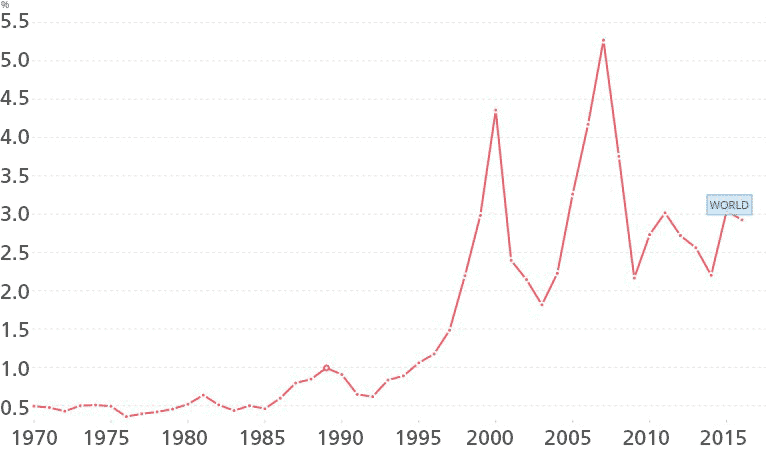

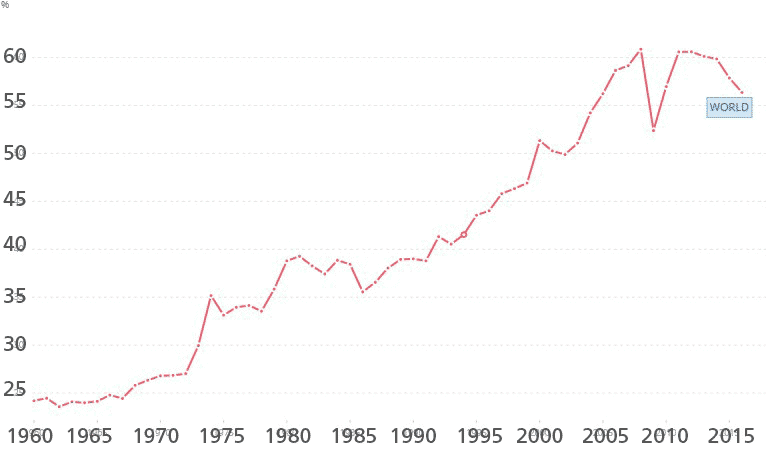

Figures on foreign direct investment (FDI) and trade (See box: Peak globalisation?) suggest that flows of FDI and trade have fallen dramatically since their peak in 2007 to 2008. The financial crisis has played a major part in this as well, of course, but the overall trend appears to suggest more than this.

Veronica Roberts, a European Union and United Kingdom competition law expert at Herbert Smith Freehills, says that one set of figures does not necessarily tell the whole story. ‘Chinese investment outside China, and especially in the EU, has been rising, and non-EU investment into the EU has been rising,’ she says. ‘I think there is still enthusiasm to invest on a global scale.’ A recent report published by Rhodium Group and the Mercator Institute for China Studies claimed that Chinese investment in the EU had increased by 77 per cent in 2016, to €35bn.

|

PEAK GLOBALISATION? |

|

Foreign direct investment, net inflows (% of GDP)

(Source: International Monetary Fund, International Financial Statistics and Balance of Payments databases, World Bank, International Debt Statistics, and World Bank and OECD GDP estimates)

Trade (% of GDP)

(Source: World Bank national accounts data, and OECD National Accounts data files)

|

However, investors are finding that governments around the world are strengthening and/or introducing new regimes to deal with and to have more scrutiny over foreign investment in their countries. ‘Investments are proceeding apace, but it’s an interesting time because governments are looking to have more control over global investment in their own countries,’ Roberts says.

Research conducted by Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer supports this view. The firm has analysed data sourced from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) alongside its own business intelligence, with the research revealing that 71 per cent of the G7 countries have strengthened or implemented their foreign investment or public interest regimes since 2014. The firm also found that since 2014 there has been a 30 per cent increase in the number of M&A transactions affected by foreign investment rules or public interest issues. This finding is based on a review of the major M&A deals, worth over $1bn, the firm has been involved in.

‘We’re also seeing that foreign investment regimes are being interpreted in an ever broader way,’ says Thomas Janssens, the Global Head of the antitrust, competition and trade practice group at Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer, who is also Senior Vice-Chair of the IBA Antitrust Committee. He cites an example from the end of 2017, when the Chinese firm Ant Financial Services Group was prevented from acquiring MoneyGram International Inc by US regulator the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS). ‘This is essentially a money transfer business, so it may not be obvious to see where the public security concern was. However, it was clear that it was a Chinese company doing the acquiring, so that may have influenced the outcome.’ (See box: Ant/Moneygram (US))

Foreign investment regimes are also changing in Europe. In September 2017, the EC unveiled a set of proposals for the screening of foreign direct investments into the EU. It suggested harmonising, to some extent, the approaches of EU Member States to investment screening around a definition of national security that takes in control of critical infrastructure and technologies, especially where acquirers have state backing. These proposed technologies extend well into ‘new’ areas, such as artificial intelligence, robotics and data management.

Citizens are anxious about not being able to control their future... due to the view that governments are no longer able to shape globalisation to benefit all

Harnessing Globalistation, European Commission, 2017

The draft legislation does not propose a power for the EC itself to screen and block foreign investments and does not mandate Member States to introduce new FDI controls. Instead, it proposes a set of minimum requirements for whatever controls Member States want to implement. It also proposes coordination and cooperation mechanisms between Member States and the EC, including the power for the EC to review investments in projects of EU interest and issue an opinion to the reviewing Member State.

In the UK, a recent discussion paper proposed the extension of the government’s powers of national security review. In the short-term, this would involve expanding the regime to cover much smaller acquisitions of target companies active in the military/dual use and advanced technology sectors. In the longer term, there could be a more significant overhaul, potentially involving the mandatory notification of transactions involving ‘essential functions’ relating to key critical infrastructure. This would cover at least certain aspects of the civil nuclear, telecoms, defence, energy and transport sectors.

In Germany, controversy over the acquisition of German robotics company KUKA in 2016 has led to an overhaul of the country’s review system for foreign acquisitions under its Foreign Trade and Payments Act.

Ant/MoneyGram (US)

A proposed $1.2bn deal between US firm MoneyGram and Ant Financial, the digital payments affiliate of China’s Alibaba, was scrapped in January 2018 after failing to win approval from CFIUS. The deal had been heavily criticised by US lawmakers, who said that the acquisition of the US cash-transfer group by an affiliate of Alibaba, in which the Chinese government holds an indirect minority stake, would pose a national security threat. MoneyGram had reportedly pledged to operate separate IT networks to Ant and prevent Ant’s investors from accessing MoneyGram’s customer data, but this was not enough to reassure the US authorities.

German legislators objected to a Chinese firm – in this case, home appliances company Midea – buying up a business developing cutting-edge technology, because that would allow them to do what an independent German company could not, which is to fully exploit that technology in the vast Chinese marketplace. (See box: Midea and Kuka (Germany))

Under revised rules, the German authorities now have double the time available (four months) to investigate acquisitions. The scope of the rules has been broadened to cover new areas, such as software providers, critical infrastructure and defence-related technologies. Officials are also able, for the first time, to investigate indirect acquisitions involving EU-based vehicles established for the purpose of a foreign acquisition.

Elsewhere in the G7, Japan has also introduced more restrictive foreign investment measures. The amended rules include prior review of the transfer of shares in unlisted Japanese companies from one foreign investor to another, and strengthened criminal and administrative sanctions for breaches of regulations regarding the transfer of certain technologies.

A crisis overblown?

Despite all this, many believe talk of a ‘crisis’ in globalisation may be overblown. ‘We’re still seeing a lot of foreign investment going in all sorts of different directions and even though regimes are being changed so governments can intervene more, there are very few cases where they do actually intervene and put a stop to transactions,’ says Roberts. ‘It’s more being able to intervene than actually having a track record of a number of prohibitions. CFIUS is by far the most active regulator on this front at the moment.’

Eric Jiang, Senior Partner at Chinese law firm Jurisino Law Group and an officer of the IBA International Trade and Customs Law Committee, says that globalisation is now so established that it should be able to withstand the current changes in US trade policy. ‘There are things going on in the US, and maybe Brexit could also be seen as a move against globalisation in a sense, but globalisation has been here for a long time, at least since World War Two,’ he says. ‘There is a solid legal mechanism established by the WTO [World Trade Organization] and multiple regional free trade agreements. It is like a great wall that cannot be pulled down overnight.’

Ambassador Hugo Paemen, a Brussels-based senior advisor for Hogan Lovells, also believes it is too soon to announce the end of globalisation. ‘I wouldn’t dramatise current events as a crisis, but globalisation has fundamental consequences, there is no doubt,’ he says. ‘Some people, the so-called “losers” of globalisation, do feel this as a serious crisis, so we have to be careful with this type of judgement.’

Ambassador Paemen has been a key player in the EU’s trade policy for the last 40 years, first as the EU Chief Negotiator during the entire length of the Uruguay Round, which led to the creation of the WTO, and later as the Head Representative of the EU to the US.

He believes resentment against globalisation is often more than a matter of just trade. ‘It’s fairly often a question of identity, with people feeling that they need to preserve their own identity, and that their freedom of action is being hindered,’ he says. ‘Also because some feel that the result of globalisation is a growing inequality in the world and in the different countries… that there is a huge gap between winners and losers.’ (See box: Globalisation and its discontents)

Some of that resentment may be misplaced, according to a report from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) that says technology should take more of the blame for rising inequality. The report states that, in most advanced economies, workers have received a declining share of national income since the early 1990s, while a growing share of productivity gains has been captured by the owners of capital. About half of this decline can be attributed to the impact of technological progress, which has made it easier to automate routine tasks. This has been more important than globalisation in affecting how much workers have benefited from economic growth. ‘Policies in advanced economies should be designed to help workers better cope with disruptions caused by technological progress and global integration, including through skill upgrading for affected workers,’ the report says. ‘Long-term investment in education as well as opportunities for skill upgrading throughout workers’ careers, could help reduce the disruptions associated with technological change.’

The US has clearly vacated the position of the champion of free trade

Thomas Janssens

Global Head of Competition, Freshfields; Vice-Chair, IBA Antitrust Committee

Technology is certainly having a huge impact on the global economy, and one notable feature of how countries are starting to dig their heels in is that they want to have some protection mechanism over foreign countries buying into their technology, as well as their infrastructure. ‘Traditionally, foreign investment regimes have been quite narrow and focused on critical infrastructure,’ says Roberts. ‘Now they’re looking at technology, they’re looking at artificial intelligence, and they are concerned that, with technology acquisitions, it’s even easier for a foreign acquirer just to switch activities to another country. It’s easier than moving a huge manufacturing plant, for example. This links to concerns about jobs being much more fungible and technology assets being really quite quickly and easily moved out of your country.’

As previously noted, the financial crisis has also had a major impact on national economic priorities. ‘The 2008 financial crash and subsequent recession signalled a pivot by governments around the world towards adopting more protectionist trade measures, primarily to shelter their economies from foreign competition,’ says David Lowe, Head of International Trade at Gowling. ‘While decades of globalisation are not being fully undone, there is an increasing protectionist climate, a tide of change affecting any and every country looking to trade internationally.’

Midea and Kuka (Germany)

The acquisition of German robotics manufacturer KUKA in 2016 by Chinese home appliances company Midea sparked controversy in Germany amid fears that key technologies were falling into foreign hands at a time when China protects its own companies against foreign takeovers. The €4.5bn deal was the largest ever for a Chinese company in Germany. Midea sought to provide reassurance about the takeover with a long-term agreement to keep its existing headquarters and management, and by saying it would allow KUKA to operate independently and help it expand in China.

Even the apparent reversal of decades of US trade policy may not be as clear-cut as it seems. ‘Recent remarks made by Makan Delrahim, the newly appointed head of the Antitrust Division at the Department of Justice, may demonstrate a more internationalist institutional view,’ says Janssens. ‘Delrahim has stated that protectionist use of antitrust laws – to discriminate against foreign firms and/or favour domestic firms – is counterproductive to domestic policy objectives as it undermines incentives to innovate and risks domestic stagnation.’

The coming year ‘will draw out the tension between Delrahim’s comments on non-discrimination, procedural fairness and transparency in competition law enforcement and President Trump’s domestic rhetoric and international trade policy,’ says Paul Yde, a Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer antitrust partner based in Washington, DC.

One of the paradoxical results of current US trade policy is that China now seems to have emerged as the world’s principal champion of globalisation. ‘The US has clearly vacated the position of the champion of free trade,’ says Janssens. ‘China seems to have seized on the opportunity, but on its own terms, because it has in many respects refused to open its own markets. The political climate there is now more welcoming of foreign investment, but when sensitive sectors such as IT and telecoms are involved, parties engaged in a transaction can expect quite close scrutiny.’ China will not be able to lead globalisation on its own at a global level, says Jiang. ‘China has benefited significantly from globalisation and has the will to move forward, but is not so experienced in globalisation’s legal mechanisms. It will need support at least from either the EU or the US.’

While decades of globalisation are not being fully undone, there is an increasing protectionist climate, a tide of change affecting any and every country looking to trade internationally

David Lowe

Head of International Trade, Gowling

Brexit – deglobalisation?

The 2016 UK refererendum vote to leave the EU has also been interpreted as a significant blow for globalisation. ‘There is a good case for arguing that the UK’s ‘Leave’ vote was a vote against globalisation rather than a vote specifically against the EU,’ says Diane Coyle, Professor of Economics at the University of Manchester. ‘The campaign slogan, “Let’s take back control”, seems to have been particularly resonant for many voters. It speaks to the frustration of the millions of Britons (and indeed citizens of other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD] countries) at their lack of agency when it comes to their standard of living and life prospects.’

Mark Carney, the Governor of the Bank of England, made a similar point when he delivered the annual Michel Camdessus Central Banking Lecture at the IMF in Washington last year. Speaking about the past 50 years, he said that the process of globalisation had led to lower inflation and interest rates in many countries. Better trade integration had improved the supply of goods, services and labour. Brexit, he said, was a ‘unique’ experiment compared with this period. ‘It will be, at least for a period of time, an example of deglobalisation, not globalisation. It will proceed rapidly, not slowly. Its effects will not build by stealth but can be anticipated.’

Conversely, there have been attempts to present Brexit as the start of a new age of increased openness to international trade for the UK. ‘The Brexit vote was a sign that the majority of the UK population were unhappy about the degree of integration that we were seeing within the EU,’ says Roberts. ‘But some UK politicians, including the Prime Minister, are talking about this being the start of “Global Britain”. This means more globalisation and Britain having a more international outlook than we have had to date. They are claiming that we have had our hands tied to some extent by needing to negotiate as part of the EU.’

Brexit is ‘a different opinion on how to deal with globalisation, or the integration that is part of it,’ adds Paemen. ‘Even Mrs Thatcher believed that the single market gave a European advantage in the global competition with the US and Japan (today, you would add China to that list). But the present UK government thinks it has to get rid of all the limits and regulations of the EU to be better able to deal with the globalised world. It’s a question of strategy.’

Globalisation and its discontents

‘What is this phenomenon of globalization that has been subject, at the same time, to such vilification and such praise? Fundamentally, it is the closer integration of the countries and peoples of the world which has been brought about by the enormous reduction of costs of transportation and communication, and the breaking down of artificial barriers to the flows of goods, services, capital, knowledge, and (to a lesser extent) people across borders.’

Joseph Stiglitz, 2002

Jiang thinks Brexit could be seen as a movement against ‘over-globalisation’. The EU is very different from what you typically see in a free trade agreement framework, even in NAFTA, he says. ‘In the EU, you have more than a free trade agreement – you have a political union as well. In particular, you have a principle of free movement of people, which eliminates borders, forcing every country to be open to immigration from other countries in the Union. This is very unusual for a typical globalisation or trade law framework. Brexit is a reaction mostly to the free movement of people principle in the EU.’

In the UK and elsewhere, globalisation has always been about much more than just trade. It is a mindset, with ramifications for culture, language and society, as well as flows of information. The rapid movement of ideas and values around the world makes it a multi-faceted phenomenon, with political, ideological and cultural dimensions. It’s a phenomenon that governments have struggled to deal with and citizens have struggled to adapt to. The current upheavals in international trade and international relations perhaps reflect a need for adjustment that is long overdue.

Jonathan Watson is a journalist specialising in European business, legal and regulatory developments. He can be contacted at jonathan.watson@yahoo.co.uk