Rule of law: arrest of Navalny’s lawyers indicates further deterioration in Russia

Yola Verbruggen, IBA Multimedia JournalistTuesday 28 November 2023

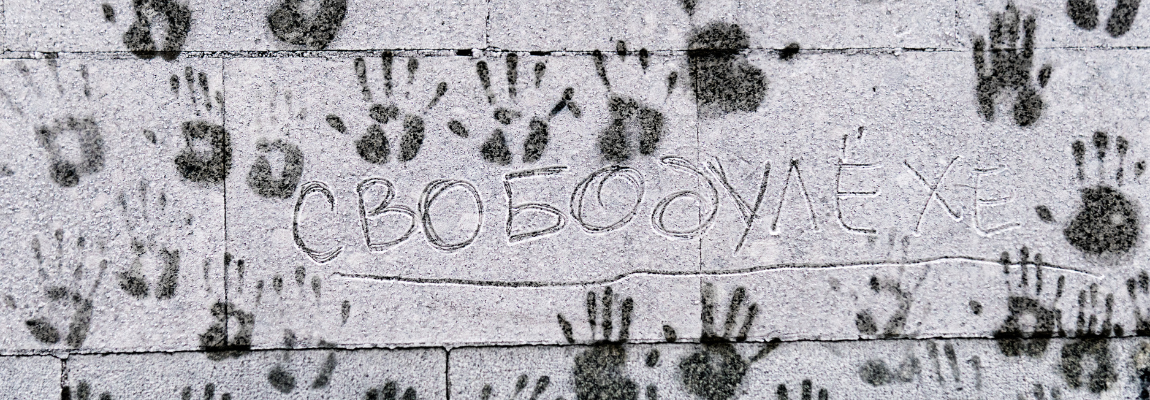

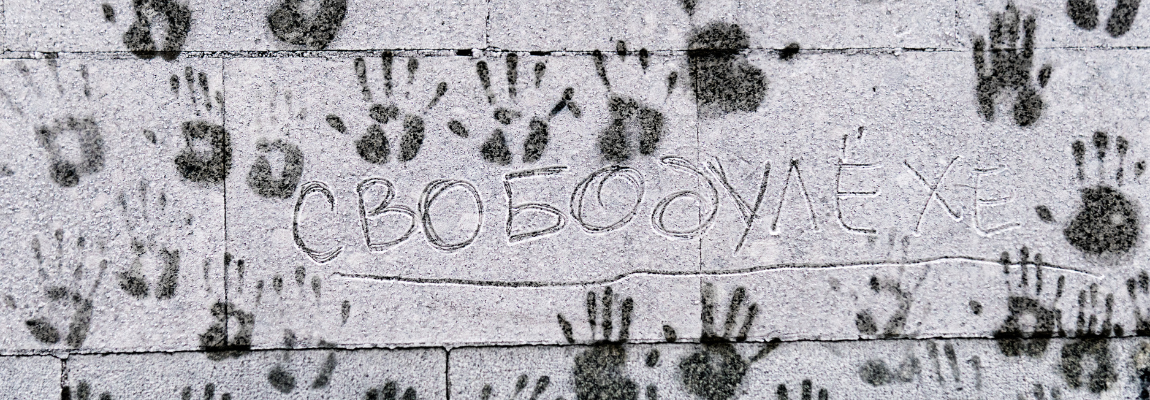

Image credit: Palm prints on a frosted wall in support of illegally arrested Alexei Navalny in Moscow during a political protest rally, translation: freedom to Alexey on January 23, 2021. Georgy Dzyura/AdobeStock.com

The arrest of Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny’s lawyers in mid-October signals a new phase in the fight to silence and isolate him, according to supporters. By defending him, the lawyers – Vadim Kobzev, Alexei Liptser and Igor Sergunin – are now accused of association with an extremist group, charges under which Navalny himself has recently been convicted. Navalny has called his lawyers’ arrest ‘illegal’.

In August, Navalny was sentenced to 19 more years in prison for charges including fraud, embezzlement and extremism, all of which he denies. This is his third conviction since returning from Germany in 2021, where he was treated after being poisoned with a Novichok nerve agent. He has repeatedly been subjected to solitary confinement and his legal team has been his only contact with the outside world.

‘Lawyers have rights under the law to visit their clients without restrictions and to conduct confidential meetings. Authorities, for a long time, did not know how to prevent lawyers from exercising their rights. In Navalny’s case, they found a way,’ says Yevgeny Smirnov, a lawyer for the Pervy Otdel (Department One) human rights organisation.

‘When a State – any State – arrests the legal profession, they attack the rule of law,’ says Melinda Taylor, Co-Chair of the IBA Human Rights Law Committee. ‘It is, in this sense, a self-cannibalisation of the roots, structure and ethos of the democratic norms to which Russia once purported to conform.’

With the help of his lawyers, Navalny has filed various suits against the Russian government, published statements on social media and spoken about his treatment in prison. ‘Lawyers in these situations provide a range of support beyond legal representation, including psychological support, helping to keep prisoners from complete isolation and addressing basic needs, such as facilitating the delivery of personal items like a toothbrush, which, while seemingly trivial, are critically important for someone in prison,’ says Ivan Zhdanov, Director of Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation.

If convicted, the three lawyers each face up to six years in prison. Additionally, their licences to practise would be suspended and any assets frozen. Another two of Navalny’s lawyers have reportedly fled the country. Despite the obvious risks, a new lawyer, Leonid Solovyov, has taken up Navalny’s case – a testament to his ‘commitment to civil duty,’ says Zhdanov.

When a State – any State – arrests [members of] the legal profession, they attack the rule of law

Melinda Taylor

Co-Chair, IBA Human Rights Law Committee

The arrests come as Navalny is about to be moved to a high security ‘special regime’ detention centre, where inmates face harsh restrictions. ‘The arrest of […] Navalny’s lawyers is a clear indication of the Kremlin’s intent to keep him in complete isolation,’ says Zhdanov. By systematically subjecting Navalny to punitive measures such as continuous confinement in a punitive isolation cell and depriving him of correspondence from supporters and even of basic writing materials, ‘the state aims to silence and cut him off from any form of external support,’ Zhdanov adds.

The IBA Human Rights Institute (IBAHRI) has called for the immediate release of Navalny’s lawyers and for all charges against them to be dropped. ‘Russia’s systematic restrictions and repressive actions against lawyers are a key component of its strategy to silence opposition,’ says Mark Stephens CBE, the IBAHRI’s Co-Chair. ‘Lawyers are not only subjected to disciplinary, administrative and criminal harassment and prosecution, but also to physical violence amounting to torture and ill-treatment. Such widespread and escalating acts of intimidation create a chilling effect on the whole system and constitute an unacceptable affront to the rule of law.’

A planned strike by lawyers to protest the persecution of legal professionals in Russia was cancelled due to a lack of support, following threats by the state, says Smirnov. He explains that the Russian Ministry of Justice intimidates the country’s bar chambers; if they show independence, they’re aware that the Russian Bar will become an analogy of the Belarusian Bar, where any resistance to the authorities in a political case means the lawyer involved sees their licence to practise revoked.

The arrests also came days after Russia’s failed bid to regain its seat on the UN Human Rights Council, from which it had been suspended following its invasion of Ukraine. The US had led the campaign for Russia’s expulsion. Richard Gowan is UN Director at the International Crisis Group and doesn’t believe that most UN members were thinking about specific issues such as Navalny’s detention when they cast their votes, but rather, ‘they were simply signalling if they approve of US and European-led efforts to isolate Russia at the UN. It is about geopolitics not human rights.’

While Russia lost the vote, it received support from 83 states – just under half of the members of the UN General Assembly. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, 141 members had supported a resolution condemning the war.

With the conflict between Hamas and Israel dominating discussions at the UN, Ukraine has become a relatively minor discussion point in New York and Geneva for the first time since early 2022, says Gowan. ‘I am sure that this is temporary, but a lot of developing country diplomats have made it clear to their Western counterparts that they will not back resolutions supporting criticising Moscow until they see real Western support for the Palestinians. The Russians are happy.’