Ukraine at war

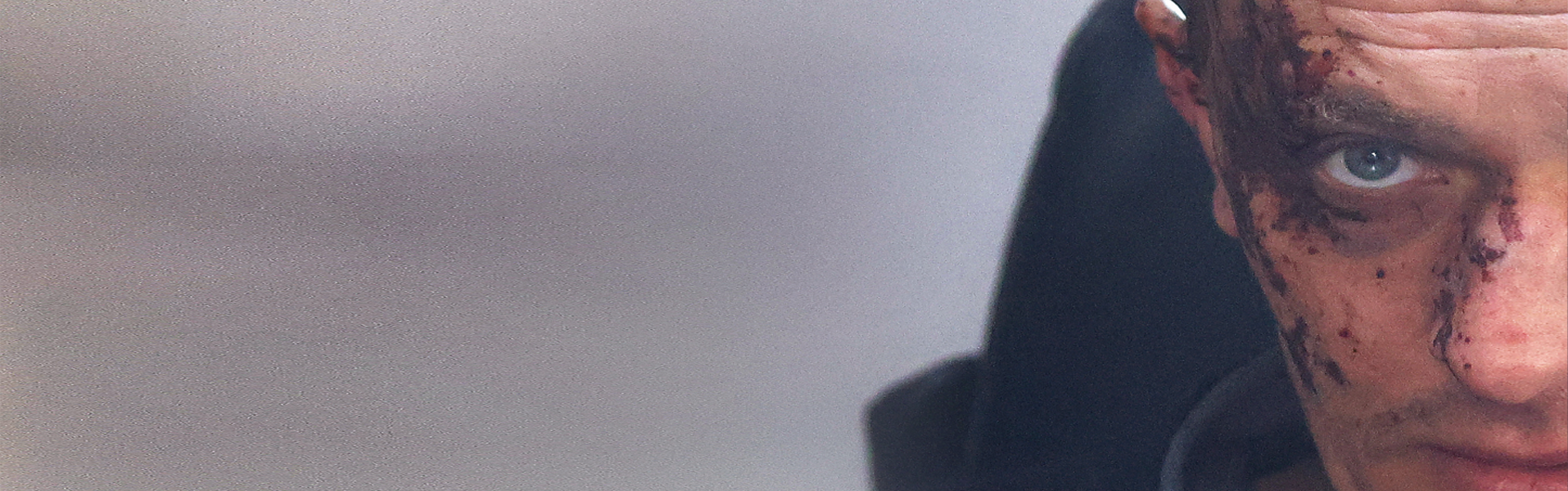

An injured serviceman looks out of an ambulance following an attack on the Yavoriv military base, amid Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, outside a hospital in Yavoriv, Ukraine, 13 March 2022. REUTERS/Kai Pfaffenbach

The Russian invasion of Ukraine shocked the world. Global Insight assesses the lead-up to the conflict, its fallout and the ongoing international efforts to hold those in power to account

It was a moment few will forget. After weeks of escalating tensions, Russian forces finally crossed Ukraine’s borders in the early hours of 24 February.

Days earlier, Russian President Vladimir Putin announced he was recognising the rebel-controlled areas of Donetsk and Luhansk as independent states. Until then, a full-scale invasion had seemed inconceivable. Suddenly, Europe was faced with its largest conflict since the Second World War.

Russia’s incursion and subsequent annexation of Crimea in 2014 was still fresh in everyone’s minds. The threat of further Russian aggression had been building for months as hundreds of thousands of troops lined Ukraine’s borders.

Nevertheless, says Olga Lautman, an expert in Russia, Ukraine and Eastern Europe and a senior fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis, the tensions behind the conflict were visible long before 2014. She says the Russian government has been using Ukraine as a testing ground for asserting its geopolitical influence abroad for decades. ‘One of the most important things to understand about Ukraine is that it has been Putin's, literally, hybrid warfare laboratory’, she says. ‘Every single thing you have seen from capture of politicians, economic capture, cyber-attacks, disinformation, division operations – everything you have seen in the West, in one form or another – was practised there for years, even before the invasion.’

An aerial view shows a residential building destroyed by shelling, as Russia's invasion of Ukraine continues, in the settlement of Borodyanka in the Kyiv region, Ukraine, 3 March 2022. Picture taken with a drone. REUTERS/Maksim Levin

During recent negotiations with other diplomatic powers, Russia demanded assurances that neither Ukraine nor Georgia would be admitted to the NATO. Public support for NATO membership has grown steadily in both countries and many Kremlin critics cited fears that prospects of NATO enlargement would act as a catalyst for Russian aggression in Ukraine.

However, Lautman says this and escalating tensons in eastern Ukraine were two of many pretexts employed by the Russian state to justify an invasion. Parallels have been drawn with the Russo-Georgia war, when Russia invaded Georgia in August 2008 after violence broke out between Georgian troops and South Ossetian separatists.

Despite this, the prospect of an outright war on European soil still seemed out of the question for many global powers in early February as they continued to deliberate over whether to escalate sanctions against Russia and adopted a gradualist approach.

All the while the Russian authorities continued to amass more troops, military equipment and blood supplies on the Ukrainian border. Lautman says there were already strong warning signs that Russia was extending its so-called ‘sphere of influence’ elsewhere in the region.

In Belarus, President Alexander Lukashenko survived a disputed election in August 2020, largely on account of the pledge of financial and political support from President Putin. The government’s renewed crackdown on society since the election and its growing dependency on Moscow signalled a perturbing turning point for the country, says Pavel Slunkin, who worked for the Belarus foreign ministry before fleeing the country in January 2021 (see box: Belarus and Russia: a Faustian pact).

‘The government has not been changed’, says Slunkin, a visiting fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations. ‘Now it seems that this small group of people who are controlling power, they go in to repress and to destroy everything in the whole society just in order to keep their absolute power, even if this means that this would reduce the sovereignty of the country and take our future.’

Further evidence of Belarus’ co-dependent relationship with Russia came at the end of February, when the electorate voted in favour of constitutional amendments that would allow Belarus to host nuclear weapons and Russian soldiers permanently, as well as extend Lukashenko’s rule. Just the previous day, the Russian President ordered his military to put Russia’s nuclear deterrence forces on high alert.

A matter of days later, Ukraine’s Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Station was hit by shelling and seized by Russian forces. General Rafael Mariano Grossi, Director of the International Atomic Energy Agency – the UN’s nuclear watchdog – said no safety systems at the plant had been affected, but that he was ‘extremely concerned about these developments’.

He is not just going for Ukraine, he's doing everything to destabilise Europe and to weaken Europe

Olga Lautman

Senior fellow, Center for European Policy Analysis, New York

There are also reports that more than 100 workers have been detained by Russian forces at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant – the site of the world's worst nuclear disaster in 1986.

Anna Babych, a partner at Aequo in Kyiv, remembers the disaster and says these developments have sparked genuine panic across the country. ‘I was six when Chernobyl happened and my mother took me out of Kyiv and we all remember the tragedy and its scale for the whole region’, says Babych, who is also Vice-Chair of the Public Policy Working Party of the IBA European Regional Forum. ‘The world should be united, but we are on the edge of being united and not preventing a third world war.’

From Belarus’ moves to artificially engineer a migrant crisis on the EU’s borders in 2021, to Russia’s continued efforts to exploit the energy crisis in Europe, Lautman says these latest efforts to flex Russia’s nuclear capabilities in Belarus are a clear indication of President Putin’s intent: ‘He is not just going for Ukraine, he's doing everything to destabilise Europe and to weaken Europe’, she says. ‘We have now the threat that Putin's military and hybrid warfare playground just expanded by another country. And he's not going to stop there because there's a Suwalki corridor, and he wants to carve that piece out in order to connect it to Kaliningrad. That poses a direct threat to Poland and to the Baltics.’

Sanctions and corruption

Economic sanctions have become the default foreign policy tool to address rule of law violations. In recent years, both Russia and Belarus have been targeted by Western sanctions time and again in response to their poor track records on corruption and human rights, including increasingly repressive tactics to contain civil society. Growing threats to high-profile outspoken critics – from the poisoning of Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny in 2020 to the removal and arrest of opposition Belarusian journalist Roman Protasevich from a grounded Ryanair plane in Minsk last May – have provoked international outcry.

Bill Browder, Chief Executive Officer of Hermitage Capital Management – once one of Russia’s biggest investment companies – has campaigned for over a decade for justice for his lawyer Sergei Magnitsky, who died in pre-trial custody in Russia in November 2009 after exposing large-scale tax fraud.

Browder says world leaders’ continued failure to curb the transgressions of President Putin and his inner circle at home and abroad led directly to this conflict in Ukraine. ‘Putin looked at all the past reaction to his atrocities’, he says. ‘He looked at what happened after Georgia. Nothing. He looked at what happened after invading Crimea. Nothing. He looked at what happened after shooting down MH17. Nothing. He looked at what happened with the Salisbury poisoning. Nothing. And so he was assuming that nothing would happen. And when he went to Ukraine, and if we had done some really aggressive, targeted sanctions in advance of him going into Ukraine, he would have seen that there would be something happening and he might not have gone through with it.’

Daria Kaleniuk, Executive Director and co-founder of the Anti-Corruption Action Centre in Kyiv, says a united, global approach to targeting Putin’s oligarchs is the only option now. ‘I believe that this will be the most effective way in terms of sanctions policy towards Russia and sanctioning on particular projects [where the] goal is not business, but the goal is actually getting more money to the Kremlin regime and getting more strategic corruption tools for the Kremlin to impose its leverage over the West.’

People gather in the basement of a local hospital, which was damaged during Ukraine-Russia conflict in the separatist-controlled town of Volnovakha in the Donetsk region, Ukraine, 12 March 2022. REUTERS/Alexander Ermochenko

She says the US administration made an unforgivable error in 2021 when it lifted sanctions on the controversial Nord Stream 2 pipeline. ‘It was a mistake of the Biden administration to lift those sanctions. I think that encouraged Vladimir Putin to go further. If you are soft, if you're implementing demands of Vladimir Putin, he will have more demands. They will never end. So you have to be strong. He understands only the language of power.’

Even before the invasion, there were growing calls to disconnect Russian from SWIFT, the international finance utility that underpins the global banking system and upon which the country’s banks rely heavily to make domestic and international payments. These calls heightened in the wake of Russia’s display of aggression on 24 February. However, cutting Russia off from SWIFT has always been seen as a last resort. In 2014, the EU threatened to expel Russia from SWIFT in retaliation for the country’s incursions into Ukraine. In 2018, the US said it would cut the country from SWIFT following Russian aggression in the Sea of Azov. Neither followed suit.

Belarus and Russia: a Faustian pact

The results of the presidential election in Belarus in August 2020 were widely disputed and provoked a mass uprising. President Vladimir Putin pledged financial and military support to help President Lukashenko silence the protesters. There was no international outcry, but the agreement effectively sealed Lukashenko’s fate as a proxy for the Putin regime and its aspirations in Europe.

In June 2021, President Lukashenko rejected EU calls to stop the flow of illegal migrants to the country’s border with the EU. Pavel Slunkin worked for the Belarus foreign ministry before fleeing the country in January 2021 after the government’s crackdown on civil society became unbearable.

Now in exile, he says President Lukashenko artificially engineered the migration crisis in retaliation for EU sanctions against Belarusian officials following the removal and arrest of opposition journalist Roman Protasevich from a diverted Ryanair plane in May.

Slunkin says this was yet another missed opportunity by the EU to keep Belarus in check. ‘I think that President Lukashenko tried to escalate the migrant situation in the expectation that the EU would need to enter into dialogue with him’, says Slunkin. ‘When the EU is ready to act as a real geopolitical player – not just looking from the side lines – this will give us the chance for change. With this escalation from Lukashenko, as with the Ryanair plane, the attention of the international society appears and then disappears, but the repression there is ongoing all the time.’

Poland's Prime Minister accused Russia’s President of being ‘the mastermind’ behind the migrant crisis. Olga Lautman, a senior fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis, says these efforts to weaponise the migrant crisis are part and parcel of a wider strategy by the Kremlin regime to destabilise and undermine European leaders.

‘What people fail to realise is that in August, you saw through Belarus, President Lukashenko, who is now his newest proxy, weaponising migrants in order to destabilise European borders’, says Lautman. ‘You saw the weaponisation of energy in order to frighten Europe, which was going into a cold winter, that they are going to be paying through the roof […] for their energy bills. So Putin again, was using these tactics of weaponising energy to destabilise Europe.’

Belarus suffered the worst losses per capita of any country in the Second World War. Older generations of Belarusians remember the devastation all too well. As global powers impose crippling sanctions on the country for its role in the invasion, and there are growing concerns that Belarusian troops are poised to assist Russian forces, President Lukashenko may learn that he has paid a high price for his re-election.

The EU has already excluded seven Russian banks from SWIFT, but it’s stopped short of including those handling energy payments given the heavy reliance of European governments on the Russian energy market. Michael O’Kane, a senior partner at Peters & Peters in London, says taking Russia out of SWIFT may no longer be the panacea that many foreign leaders believe it to be. ‘Since 2014, Russia has seen this coming’, he says. ‘Russia has been building up its own alternative to SWIFT, which it will be wanting to use particularly vis-à-vis transactions with China, for example. Freezing assets of the Central Bank is a much bigger deal.’

Since the invasion, unprecedented sanctions have been imposed on Russia by key global powers, causing huge upheaval across the international energy and finance markets. The mounting list of banks, oil and gas companies, financial payment providers, technology companies and even law firms severing links and long-standing relationships with Russia has been revealing in more ways than one: it demonstrates, first, just how much business is conducted with Russian clients worldwide. Second, it shows that companies not directly affected by the sanctions have realised the detrimental reputational impact of having – or appearing to have – even the slightest association with Putin’s corrupt regime.

If you are soft, if you're implementing demands of Vladimir Putin, he will have more demands

Daria Kaleniuk

Executive Director and co-founder, Anti-Corruption Action Centre, Kyiv

It’s no secret that the hidden wealth of rich Russians close to the Kremlin has been laundered overseas for decades. US economist Paul Krugman estimates that as much as 85 per cent of Russia’s GDP has passed through banks and financial institutions across many of the world’s top financial centres.

Governments have made limited progress in containing the scourge of so-called ‘dirty money’ and repeatedly missed opportunities to establish public registers that reveal the individuals behind companies. The UK government, which has been strongly criticised for its failure to keep illicit funds out of the country, said it was expediting the passage of its previously shelved Economic Crime Bill in the wake of Russia’s military aggression in Ukraine.

Pascale Dubois, a member of the IBA Anti-Corruption Committee Advisory Board, previously led the World Bank's anti-fraud and anti-corruption efforts. She says the Ukraine conflict has finally made the case for stopping the scourge of illicit wealth undeniable. ‘The Ukraine crisis now is making the dangers of kleptocrats known to the public at large and how it’s affecting all of us’, she says.

Jitka Logesova, a fellow member of the IBA Anti-Corruption Committee Advisory Board and a partner at Wolf Theiss in Prague, agrees the Ukraine conflict could be a real moment of reckoning for governments and test political will to tackle illicit financial flows once and for all. ‘London and Paris are not the only cities with huge assets owned by oligarchs or even Putin, through his friends of course’, she says. ‘Munich is another one, but Germany too has been very cautious in its approach towards dirty money. Switzerland is another example. I hope that what happens in Ukraine will change the political situation in many countries and willingness to jointly go after unexplained wealth.’ In a sharp deviation from the country’s historic neutrality, Switzerland announced at the end of February that it had adopted all sanctions imposed upon Russian individuals and companies by the EU.

Accountability and justice

The immense humanitarian toll of the Ukraine conflict is already emerging. Hundreds are believed to have been killed and thousands more injured. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimates that at least two million refugees have fled so far to neighbouring Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and other EU countries. More are sure to follow. Frantic scenes of hysteria at train stations and vehicles queuing for kilometres at the country’s borders are becoming an all-too familiar sight.

Kaleniuk says there are generations of Ukrainians who are reliving the horrors of the Second World War. ‘My grandmother – she's 87 – remembers well how Nazis invaded her village’, she says. ‘It was not easy times, and she is from Ukraine, just 100 miles from Kyiv. This generation of elder Ukrainians, they have this fear of war in their blood. She doesn't want to have war again, and she doesn't treat Russia as a friend obviously.’

A tank with the letters "Z" painted on it is seen in front of a residential building which was damaged during Ukraine-Russia conflict in the separatist-controlled town of Volnovakha in the Donetsk region, Ukraine 11 March 2022. REUTERS/Alexander Ermochenko

Babych fled Kyiv with her young family to a neighbouring EU country soon after the invasion. She says it’s very hard for Ukrainians – young and old – to comprehend what’s happening. ‘Some people have left for smaller, more rural villages as they think they’re less likely to get shelled there’, she says. ‘Others aren’t leaving Kyiv as they don’t want to run from their homes. They believe in the better outcome.’

Babych knows she’s incredibly lucky to have the financial means to get out of the country safely. But like many of those who have fled, she worries for those left behind – her male friends and relatives that are prohibited from leaving the country, for others, like her elderly grandmother, who are too frail to leave. ‘The reality is that there are people – at least I know one personally – who are giving birth in bomb shelters’, she says. ‘This generation of Ukrainians will never forgive bombed civilians, hospitals, killed children and genocide against Ukrainian people.’

Considerable steps have already been taken to try and ensure that the perpetrators will be brought to justice. Just four days after the invasion, on 28 February, the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC), Karim Khan QC, announced he was opening an investigation into alleged war crimes and crimes against humanity in Ukraine ‘as rapidly as possible’ after 39 countries referred the situation to the Court.

IBA Executive Director, Dr Mark Ellis, says the investigation will ensure Putin’s regime is held to account. ‘President Putin may see himself as untouchable’, he says. ‘However, he cannot escape justice. Under international law, there is no impunity nor statute of limitations for the types of atrocities being committed in Ukraine.’

Leila Sadat, the special adviser on crimes against humanity to the ICC Prosecutor, told Global Insight that the state referral allowed the Court to build immediately on its findings from previous preliminary examinations into alleged crimes committed in Ukraine in the run-up to the Crimea invasion and its aftermath.

The ICC has already dispatched an advance team to Ukraine to look at evidence collection, witness protection and other issues to aid its investigation. Sadat says the timing is crucial before the situation gets even worse. ‘I think the concern now is that if Russia becomes an occupying power in certain parts of Ukraine, the potential for crimes against humanity and war crimes could become even more significant with respect to women and children and with respect to detainees’, she says. ‘I'll be closely working with the Office on any issues relating to crimes against humanity.’

This generation of Ukrainians will never forgive bombed civilians, hospitals, killed children and genocide against Ukrainian people

Anna Babych

Partner, Aequo, Kyiv

Ukraine has also called on the International Court of Justice (ICJ) to impose an emergency order to stop Russia committing crimes against humanity and war crimes. Although the hearing in The Hague on 7 March was boycotted by Russia, the ICJ said it would follow a fast-track procedure to expedite its ruling.

There has also been a strong push by international legal experts towards establishing a special international criminal tribunal to specifically address the crime of aggression against Ukraine – an area that doesn’t fall under the ICC’s jurisdiction.

Although the ICC prosecutes war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide and the crime of aggression, if a state is not party to the ICC – which Russia is not – then individuals from that country cannot be prosecuted by the Court for the crime of aggression. The UN Security Council can refer alleged crimes of aggression committed in any country to the Prosecutor, but it’s likely that Russia, as a permanent member of the Security Council, would block such a move.

Philippe Sands QC, a barrister at Matrix Chambers and a professor at University College London, is spearheading the project, which also has the backing of Ukraine’s Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba, his special adviser Mykola Gnatovsky, former UK Prime Minister Gordon Brown and numerous international legal experts.

The proposals were launched in an online event hosted by Chatham House on 4 March. Sands says the Ukraine crisis has revealed that sanctions alone will not be enough to stop the conflict and that a special tribunal focused on the crime of aggression would help ‘leave no stone unturned’.

Kuleba, who spoke during the event via video link from Ukraine, said he welcomed the move. ‘When bombs fall on your cities, when Russian soldiers rape women in the occupied cities […] it is difficult of course to talk of the efficiency of international law’, he said. ‘But this is the only tool of civilisation that is available to us to make sure that, in the end, all those who made this war possible will be brought to justice.’

There needs to be the strongest possible response from the international community to the invasion of Ukraine, and every possible legal channel should be explored

Philip Leach

Professor of human rights law, Middlesex University, London

Professor Philip Leach, an expert in human rights law at Middlesex University, litigated numerous cases against Russia over almost two decades at the helm of the European Human Rights Advocacy Centre. He says the initiative would fill an important gap in international law. ‘There needs to be the strongest possible response from the international community to the invasion of Ukraine, and every possible legal channel should be explored’, he says. ‘This particular proposal seeks to plug a clear gap in the international criminal justice armoury, namely the ability to prosecute the crime of aggression as regards Ukraine.’

The move would ‘set a very good precedent to be applied in the cases of future acts of aggression’, agrees Justice Richard Goldstone, the former Chief Prosecutor of the UN International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia and Honorary President of the IBA’s Human Rights Institute (IBAHRI).

Baroness Helena Kennedy QC, Director of the IBAHRI, is also a signatory to the initiative, and says an ad hoc tribunal of this kind would be the vital ‘piece missing in the steps already being taken to address Putin’s gross breaches of the rule of law’.

Lana Sinichkina is a partner at Arzinger in Kyiv. She says the crisis in Ukraine should be a wake-up call for the world. ‘The international security system just failed and it didn't fail today or yesterday, it failed several years ago already’, she says. ‘The Security Council of the United Nations cannot do anything with the aggression of Russia, unfortunately, and we see now that different countries have different stakeholders that take different positions as regards to the Ukrainian situation, and they take this position not based on sound mind or on sound reasons and arguments.’

The UN General Assembly has condemned Russia's hostile actions in Ukraine and called for the withdrawal of troops. In an emergency session held on 1 March, 141 of the 193 member states voted for the resolution, 35 abstained. Only four countries voted against Russia withdrawing troops – Belarus, Eritrea, North Korea and Syria. Notably, three long-standing allies – China, Cuba and Nicaragua – were among those that abstained.

Sinichkina hopes the conflict in her country will act as a warning to the international community at large. ‘Today, the world is very small and I'm absolutely confident that everybody in his or her place may do something to protect the world and to protect values and international law’, she says. ‘I do hope that countries around the world look in a more serious way and understand that today it's not Ukraine and its independence that’s at stake. Today, the general international architecture of the world and of peace is at stake.’

Ruth Green is the IBA Multimedia Journalist and can be contacted at ruth.green@int-bar.org