Ukraine and the energy markets

Sophie CameronWednesday 1 February 2023

The war has had a major impact on oil and gas supplies. Global Insight assesses the implications.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has devastated the country, sending tremors across the world and contributing to food and energy crises. Inevitably, given its dependence on Russian energy, Europe has been significantly affected. By the end of 2022, Ukraine and Europe were preparing for a hard winter, with talk of blackouts and shortages of gas supplies. Fortunately, abnormally warm temperatures across Europe and the steady flow of gas into underground storage facilities have meant the situation has not proven to be quite as dire as some predicted, so far.

Regulating the domestic energy market is a key responsibility for all national governments and a difficult task at the best of times. They aim to ensure the efficient and effective operation of industry and society. The conflict in Ukraine has made this all the more difficult for jurisdictions and energy markets globally.

The energy trilemma

The World Energy Council's Energy Trilemma describes three policy concerns, which can be hard to reconcile: energy equity, which aims to make energy affordable for consumers; energy security, which seeks to ensure the reliability of energy sources; and energy sustainability, which seeks to minimise environmental harm.

Phillip Ashley, a partner at CMS in London who specialises in energy sector disputes, explains that ‘the security of supply issue has moved swiftly up the agenda as many countries are dependent on Russia for oil and gas. The energy crisis we are facing now has shown that some elements of policy have been deeply wrong. A few years ago, for example, the UK was not importing gas, and now we are in a situation where security of supply has declined and the costs are exorbitant’.

The energy trilemma poses difficult questions that can place the three policy areas in conflict. For example, is a government willing to build nuclear capacity in order to increase the security of supply? To what extent can a country bring in new technology? Are blackouts a solution to energy shortages? What alternative supplies are available? Ashley believes that, in the UK, such decisions should have been taken more than 20 years ago, and that it’s now urgent that these policy decisions are made as soon as possible to give energy companies certainty going forward.

The energy crisis we are facing now has shown that some elements of policy have been deeply wrong

Phillip Ashley

Partner, CMS

Events in Ukraine have led to a number of different approaches being taken by governments as they engage with the challenge of the energy trilemma. ‘For those countries rich in natural resources, they will continue to promote themselves for investment on the pretence of energy-investments’, says John Zadkovich, a partner at Penningtons Manches Cooper. ‘The dilemma is that most are in emerging markets and some of the states have a history of expropriation, political instability and corruption, so stimulating their economy through foreign investment will be challenging.’

Zadkovich sees other governments now promoting themselves as ‘green energy’ hosts. ‘While that is laudable, certain jurisdictions are emerging markets with the same issues, as well as a lack of infrastructure which only increases capital outlay’, he says. Meanwhile, others still are pressing for private capital to help correct the situation and stimulate growth in the energy sector. ‘That’s all very well, but again windfall taxes, bureaucratic delays [and so on] do not engender investor confidence’, says Zadkovich.

Mind the gap

Russia is the leading exporter of natural gas worldwide. According to Statista, in 2021, Russia exported 201.7bn cubic metres of gas via pipelines and 39.6bn cubic metres of liquified natural gas (LNG). Many EU Member States are dependent on Russian gas, with the majority receiving at least a small share of gas from Russia and a handful being totally dependent – prior to the war. Russia accounted for nearly 40 per cent of Europe’s natural gas supply during 2021, a third of which transited Ukraine, and 25 per cent of Europe’s oil supply.

Following the invasion, exports of Russian gas to Europe were severely affected as European countries sought to reduce their reliance on Russia and adhere to sanctions imposed on the country. Gazprom, the Russian majority state-owned energy company, announced a decline in exports to key foreign markets of 46 per cent in 2022, and gas production shrank to 412.6bn cubic metres. Statistics published by the Russian government also claim that Russia cut its exports of natural gas by more than half in 2022 to 100bn cubic metres, mainly due to a decline in exports to EU Member States.

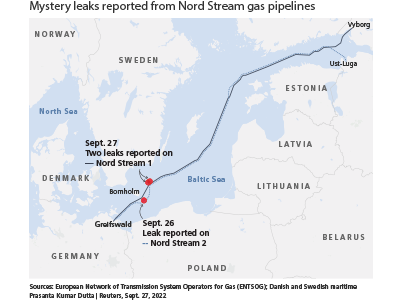

In February 2022, Germany announced the suspension of the certification process for Nord Stream 2. This prevented the new natural gas pipeline, which runs from Russia to Germany through the Baltic Sea, from becoming operational. Simultaneously, the US imposed sanctions on Nord Stream 2 AG, its Chief Executive Officer Matthias Warnig and its corporate officers. US Secretary of State Antony Blinken stated that ‘this action is in line with the United States’ longstanding opposition to Nord Stream 2 as a Russian geopolitical project and the President’s commitment that Nord Stream 2 would not move forward following the beginning of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine’.

The situation became more complex still in September, as a series of explosions hit both the Nord Stream 1 and Nord Stream 2 pipelines. The explosions, which resulted in underwater gas leaks, were the result of sabotage, according to the Swedish security service. Russia has denied involvement.

Leaks reported from Russian Nord Stream pipelines, 27 September 2022. Reuters Photographer/REUTERS

Political risk has materialised in an unexpected way. Everybody who relied on oil and gas from Russia has had to reassess their positions

Dr Matthias Lang

Vice Chair, IBA Energy, Environment, Natural Resources and Infrastructure Law Section

Dr Matthias Lang, Vice Chair of the IBA Energy, Environment, Natural Resources and Infrastructure Law Section and a partner in the International Energy & Utilities Sector Group at Bird & Bird, Düsseldorf, tells Global Insight that ‘Russia had for many years been considered to be a reliable supplier of oil and gas. That is over. Political risk has materialised in an unexpected way. Everybody who relied on oil and gas from Russia has had to reassess their positions’.

For instance, the German energy transition (Energiewende) was largely built on an abundant supply of Russian gas on the way to ever-increasing renewable energy. The dates for Germany’s nuclear exit, the lignite (brown coal) exit and the hard coal exit, were calculated based on reliable supply of Russian gas. Now, the German government has had to quickly change its schedule and its means of acquiring energy to avoid shortages.

‘Complacency among some governments and their dependency on Russian energy – despite previous denials to the contrary – has left them in a quandary’, says Zadkovich. ‘The shortage of Russian energy has left them looking for alternative supplies. But the majority of oil and gas supplies are not sold at spot prices and are instead long-term supply contracts, so there is not an immediate supply. Equally, many renewable energy projects – and technologies – are either premature or don’t provide baseload power, so there remains a lacuna in the sector.’

Zadkovich adds that some European countries were able to source LNG from non-Russian suppliers and thus ensure sufficient supply during the winter. But, he says, ‘that winter itself was unusually warmer than normal, so less power was actually required. More forward thinking is required for the short and long term’.

RE-powering Europe

The European Commission published its REPowerEU strategy in March 2022. The plan sets out joint European action for more affordable, secure and sustainable energy, with the stated aim of reducing Europe’s dependence on Russian fossil fuels as quickly as possible. ‘Following the invasion of Ukraine by Russia, the case for a rapid clean energy transition has never been stronger and clearer’, said the Commission.

Construction of the Nord Stream gas pipeline. Mike Mareen/AdobeStock.com

The plan of action will largely be the responsibility of individual EU Member States to implement. It will include measures to increase the production of green energy, diversify supplies and reduce demand. While encouraging its members to move away from Russian gas, the bloc has been seeking alternative gas supplies from countries such as Japan, Qatar and the US. The plan also includes short-term action to mitigate escalating retail prices and support heavily exposed companies, and to ensure sufficient gas storage for colder weather.

Full implementation of the Commission’s proposals would, according to the document, lower EU gas consumption by 30 per cent, equivalent to 100bn cubic metres, by 2030. In addition to this, the Commission claims that together with gas diversification and more renewable gases, energy savings and electrification have the potential to jointly deliver at least the equivalent of the 155bn cubic metres-worth of gas previously imported from Russia.

Lang says each EU Member State will have to create its own set of solutions and that EU institutions will need to agree on how best to coordinate efforts. ‘We will all need a realistic assessment of what is physically possible, commercially possible and reasonable, and politically possible and reasonable. Personally, I think we should look at the possibilities in that order’, he says. ‘As general concepts, energy conservation and development of alternative sources are two key areas of focus.’

Germany, for example, announced in January 2023 that it has completely stopped importing natural gas, oil and coal from Russia. Lang also highlights that the German government has already revised a large number of statutes as it tries to find solutions. ‘Conceptually, we are seeing an increase in the role the state plays, both as it relates to state spending and regulatory requirements’, he explains.

For Zadkovich, recent developments have accelerated the need for the energy transition – as the European Commission itself has highlighted – ‘but the legal/regulatory environment is typically slow to respond as policy makers and bureaucrats struggle to adapt’. He explains that private capital earmarked for energy transition technology and projects may be withheld pending clear – and ideally more uniform – laws. ‘This has however been tempered somewhat by the large government pledges and subsidies proposed by the US and the EU, which has caused investors and vendors to revisit renewable power opportunities’, he says.

Sanctions both bite and boost

EU sanctions have also driven Member States away from Russian energy. In June, the European Council adopted a sixth package of sanctions that, among other things, prohibits the purchase, import or transfer of crude oil and certain petroleum products from Russia to the EU. The restrictions have been set to apply gradually: within six months for crude oil and within eight months for other refined petroleum products. A temporary exception applies for imports of crude oil by pipeline into those EU Member States – namely Bulgaria and Croatia – that, due to their geographic situation, have a specific dependence on Russian supplies and have no viable alternative options.

In another significant joint effort in December, Australia, the EU and G7 member countries jointly set a cap on the price of seaborne Russian oil at $60 per barrel in order to further restrict sources of revenue to Russia and preserve the stability of global energy supplies. The price cap’s stated aim is also to help protect consumers and businesses from disruptions to global supply chains. Phillip Ashley from CMS says that ‘The impact of these measures may be limited in the short-term. However, the medium-term impact is likely to be more significant – as it will result in a fundamental redesign of the West’s energy markets’.

Energy in wartime – the impact on Ukraine

It’s estimated that nearly 11 million citizens have fled across the border of Ukraine, and almost four million have become internally displaced persons. Naftogaz, Ukraine’s state-owned oil and gas company, has reported multiple instances of damage to its domestic pipeline network.

The war has seen air attacks on Ukrainian oil depots and refineries, resulting in Ukraine’s complete dependency on the EU’s petroleum products, especially motor fuels. As Ukraine’s domestic economy has come to a standstill, the consumption of oil and gas in the country has dropped sharply, presenting unprecedented challenges for energy companies operating there. The Ukrainian government and its Association of Gas Producers have, however, made concerted efforts to mitigate these issues.

In March 2022, the Ukrainian Ministry of Energy introduced a prohibition on exporting Ukrainian natural gas. The ban included gas stored according to Ukraine’s ‘customs warehouse’ regime in underground gas storage facilities, which allows companies to hold gas in Ukraine for up to three years without customs clearance. At the same time, oil and gas producers found that many industrial customers were suspending their operations in Ukraine, substantially reducing their gas consumption.

Maksym Sysoiev, a partner and member of the Global Energy Group in Dentons’ Kyiv office, explains that early in the war Ukrainian privately owned gas producers faced a quandary, as ‘they had no buyers in the domestic market and could not export their gas abroad. At the same time, they were obliged to pay royalties at the moment of gas production – often without the possibility of selling the commodity – based on average prices at European gas hubs and average import gas prices. However, changes were made to the Tax Code of Ukraine, according to which royalties for extracted gas began to be calculated from 1 April exclusively after the sale of the resource, which partially solved the problem’.

Sysoiev says the Ukrainian government’s actions have helped the industry deal with the unprecedented challenges. However, the demand for gas in Ukraine remains low and is even declining, which means that private gas producers are unable to sell all their produced gas even for relatively low local prices. ‘Naftogaz may buy such gas from private producers, but the government has not yet introduced the mechanism to finance such procurement, nor the methodologies for setting prices and carrying out such purchases’, he says.

Among other things, the war has led to a suspension of multiple long-term gas investment projects in Ukraine, including offshore in the Black Sea, and set back the potential development of hydrogen and the green economy. Artem Petrenko, Executive Director of the Association of Gas Producers of Ukraine, explains that ‘It is important for Ukraine to have diversified energy supplies, to achieve its green goals and most importantly to achieve energy independence’.

For energy companies, the impact of these sanctions varies. Zadkovich says that, for most oil and gas producing companies, there have been benefits in that the shortage of supply brought about by sanctions has resulted in a price rise and they have increased production accordingly. ‘Those in oil and gas services industries have also seen an increase as investment in exploration and development has returned and they leverage off the renewed and increased oil and gas production’, he explains. ‘Similarly, the downstream, in particular shipping and floating storage and regasification units, have seen an increase in orders as some states that lack land-based gas and regassification infrastructure seek alternatives in the form of new and/or refitted vessels to accommodate demand.’

Other companies – for example, those producing electricity from oil or gas – have felt the adverse effect of the higher prices, which has caused some to cease operating or come close to shutting. Domestic price caps, while helping consumers, have done little for the electricity providers. ‘Finally, some renewable energy companies have seen a slight downturn in investment as certain investment capital is attracted to the short to mid-term higher returns offered by oil and gas producers’, says Zadkovich.

Putting aside the issue of sanctions, for some investors and traders the idea of entering into any business with Russian parties is repugnant from a moral and/or an ESG perspective, regardless of energy security and other concerns. ‘For others, theirs is a more mercantile approach and it’s business as normal, all the while looking for an opportunity upon which to capitalise’, says Zadkovich.

Preparing for spring

The recent fall in day-ahead natural gas prices, which has seen European gas prices return to levels last seen before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, largely reflects a winter in Europe that was warmer than anticipated, as well as alternative imports and French nuclear power stations going back online. But Ashley highlights that despite the respite, this fall in gas prices ‘does not reflect a significant shift in the medium-term demand/supply balance so as to impact the underlying issues giving rise to the crisis’. If the winter remains mild in Europe, however, it’s expected that gas prices will continue to fall throughout spring, as storage levels will remain greater than estimated.

Many renewable energy projects – and technologies – are either premature or don’t provide baseload power, so there remains a lacuna in the energy sector

John Zadkovich

Partner, Penningtons Manches Cooper

In Ukraine itself, Artem Petrenko of the Association of Gas Producers of Ukraine emphasises that the country has overcome a great number of barriers that have inhibited the oil and gas industry since the beginning of the war, but unfortunately, as the conflict is ongoing, significant challenges remain. ‘Preparation for the 2023/2024 cold season will be a challenge’, he says. ‘The International Energy Agency predicts that the gas deficit in the EU may reach 30bn cubic metres by next summer. The EU plans to jointly purchase gas and focus on LNG imports. Given the current warm winter, we think that the agency may revise the gas deficit forecast downwards.’

Zadkovich expects the global energy markets to improve in terms of deals, trade and capital as China reopens after effectively being closed for years due to its Covid-19 lockdowns. ‘Recent inflation figures for some markets have shown that prices are moderating and this in turn has resulted in portfolio investors piling back into oil and gas futures and options’, he says. ‘That said, other domestic markets are floundering, falling into a recession and combating inflation. This will adversely impact the energy markets; less capital, higher prices and the prospects of windfall taxes will deter investment in the sector in those states.’ It seems that, as with much in the world right now, energy markets are likely to remain in flux and highly unpredictable for the foreseeable future.

Sophie Cameron is a freelance journalist. She can be contacted at sophiecameron2@googlemail.com

Image credit: bennymarty/AdobeStock.com