Trade in a time of turmoil

Margaret TaylorTuesday 14 May 2024

Following the Second World War, trade became a way of fostering peace between nations. Global Insight investigates whether, as more countries turn in on themselves, that ideal has been lost.

When it met in January the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) expressed ‘profound concerns’ over escalating disruptions to international trade, with shipping routes in the Black Sea, Red Sea, Suez Canal and Panama Canal affected by issues ranging from geopolitical tensions to the climate crisis.

Ominously, a month later World Trade Organization (WTO) negotiators failed to break a deadlock over proposed reforms despite extending their ministerial conference by a day in a bid to thrash out a deal. Members were unable to reach consensus on agriculture, food security or fisheries subsidies, and, while progress was made on overhauling the WTO’s dispute resolution process, ultimately nothing concrete was agreed.

Not that the deadlock is particularly surprising. In its Political Risk report for 2024, insurance broker Marsh found that trade barriers introduced over the past five years to protect domestic industries have increased ‘the frequency and severity of trade disruption and distortion’. Similarly, in a blog published earlier in 2024, Ayhan Kose and Alen Mulabdic, Deputy Chief Economist and a senior economist respectively at the World Bank Group, noted that while international trade has been ‘a key engine of global prosperity since the fall of the Berlin Wall’, it has now all but ‘ground to a halt and is set to remain anaemic in the coming years’.

Theatres of conflict

Raj Bhala, Diversity and Inclusion Officer on the IBA International Trade and Customs Law Committee and Brenneisen Distinguished Professor in the School of Law at the University of Kansas, says there’s ‘so many dimensions’ to the disruption to trade, but points to the Sino-American trade war – which has been raging since 2018 – as one of the key drivers.

Sources: LSEG; Planet Labs; Maps4News; Shoei Kisen Kaisha/REUTERS

After he was elected US President in 2017, Donald Trump accused China of everything from unfair trading practices to intellectual property theft, while China retaliated by alleging that the US was trying to curb its rise as an economic power. The two nations imposed tariffs on hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of one another’s goods and in the process upended a decades-long effort to reduce global trade barriers. Though the overall impact was to increase trade opportunities for other countries – the so-called ‘bystander effect’ – the disruption it caused to supply chains has been lasting.

And, while the trade war between the world’s superpowers has shown no signs of abating since Joe Biden replaced Trump as US President in 2021, further developments have only added to the pain. Dalton Albrecht, Co-Chair of the IBA International Commerce and Distribution Committee and counsel at EY Law in Toronto, says that what began when the Covid-19 pandemic brought international trade to its knees in 2020 has escalated in the years since as a result of ongoing conflicts in Europe and the Middle East.

‘We’ve seen disruption, originally with Covid then with various conflicts – the war in Ukraine and the conflict [between] Israel and Hamas have really exacerbated a trend that had been happening for a while’, he says. ‘Covid disrupted supply chains then people were ordering more goods online but there weren’t enough ships and then there were sanctions that came out of the conflicts, on Russia for example – if you don’t have banking access you can’t deal with your suppliers because you can’t pay them.’

The war in Ukraine and the conflict [between] Israel and Hamas have really exacerbated a trend that had been happening for a while.

Dalton Albrecht

Co-Chair, IBA International Commerce and Distribution Committee

He says that additional trade friction has been created as countries have introduced legislation to crack down on unfair labour and modern slavery. ‘These are enforced by customs – companies have to prove their goods are not made with slave labour or child labour’, he explains. ‘When you pile all that on with the original Covid problems it causes a lot of issues with trade.’

Just as America’s protectionism has been felt far beyond the borders of the US and those of its opponent, Russia’s war in Ukraine and Israel’s in Gaza have further unsettled the global trading system. Ukraine, for example, has in recent times been a key exporter of cereals to the African continent but has seen its exports plummet since the Russian invasion in 2022. The nations it exports to have been forced to adjust their trading patterns as a result.

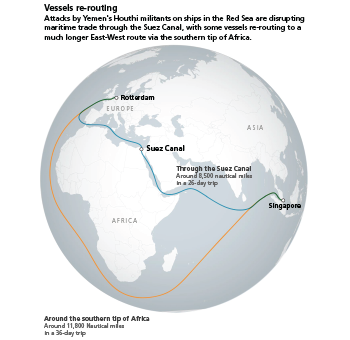

Similarly, as a result of the conflict in the Middle East and attacks on international shipping by the Houthi rebels, based in Yemen, goods that would normally have made their way through the Suez Canal have been redirected around the Cape of Good Hope, adding days to transit times and leading to an increase in costs.

For Carol Monteiro de Carvalho, Co-Chair of the IBA International Trade and Customs Law Committee and a partner at Brazilian firm Monteiro & Weiss Trade, this highlights that the impact of conflict can be felt far beyond the countries involved. ‘Conflicts affect the flow of international trade directly, either by breaking up supply chains or by the collateral effects of some conflicts, such as the adoption of sanctions’, she says. ‘That can have the effect of interfering in international business, including extraterritorial application in some cases. The infrastructure of the countries in conflict could also be affected, interfering with international logistics and the search for alternative routes.’

Freight lorries queue to enter the Port of Dover, Britain, 27 April, 2022. REUTERS/Henry Nicholls

It has an impact on future trade too. ‘Conflicts certainly have the effect of delaying or even preventing some [trade] deals, whether because of international sanctions, the risk of non-payment or [a lack of] legal predictability’, Monteiro de Carvalho says. ‘Negotiating an international agreement can take several years and, obviously, conflicts directly related to or with a direct impact on member states affect negotiations.’

Trade-lite trade deals

Yet, against this backdrop, trade deals are still being signed. In March, for example, the Indian government, which has been notoriously protectionist since Prime Minister Narendra Modi came to power in 2014, completed a deal with the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) that will bring down barriers between India and EFTA members Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. The agreement, which took 15 years to negotiate and so pre-dates the Modi administration, will see India lift import tariffs on most industrial goods in return for $100m of investment into its pharmaceuticals, machinery and manufacturing sectors, among others, over the next 15 years.

Chapter 11 of the India-EFTA deal is called Trade and Sustainable Development […] even five years ago, India would never have agreed to that

Raj Bhala

Diversity and Inclusion Officer, IBA International Trade and Customs Law Committee

On the one hand the deal is expected to give the EFTA countries a significant economic uplift by allowing them access to India’s vast market, while on the other it’s anticipated that it will boost the Make in India programme – a government initiative aimed at strengthening domestic manufacturing through the modernisation of key infrastructure. ‘This landmark pact underlines our commitment to boosting economic progress and creating opportunities for our youth’, Modi said when the deal was finalised. ‘The times ahead will bring more prosperity and mutual growth as we strengthen our bonds with EFTA nations.’

At the same time, the UK, whose own post-Brexit trade talks with India stalled just days after the EFTA deal was sealed, has entered into an economic partnership with Nigeria – its first with an African nation. The Enhanced Trade and Investment Partnership, which was signed by UK Business and Trade Secretary Kemi Badenoch and Nigerian Federal Minister of Industry, Trade and Investment Doris Nkiruka Uzoka-Anite in April, will pave the way for collaboration between the two countries’ legal and financial sectors and also enable UK education providers to establish themselves in Nigeria.

Indian PM Modi shakes hand with Nigeria President Tinubu for the G20 Summit in New Delhi, India, 9 Sept, 2023. Evan Vucci/Pool via REUTERS

‘This partnership with Nigeria […] will allow us to work together and seize the opportunities that lie ahead’, Badenoch said after closing the deal. ‘Nigeria has one of the fastest-growing economies in the world. UK businesses have already seen huge success here and I look forward to seeing how we continue to grow this relationship.’

For Yves Melin, Vice-Chair of the IBA International Trade and Customs Law Committee and a Brussels-based partner with Reed Smith, such warm words expose something else about trade deals – that, in many ways, they’re not really about trade at all. Melin believes that countries are actually signing free-trade agreements for reasons ‘such as security or defence or to try to create groups of aligned countries’.

‘If you look at free trade, after the Second World War the US created the GATT [General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade] and the winners joined’, says Melin. ‘Then in the 1990s we had the WTO, which was the GATT on steroids with [many] more countries – there was no Russia or China but the idea was that more countries could join. The philosophy of the time was that free trade is good for you, it’s good for us, and it makes everybody richer, which is not really true – it makes the world richer, but not everybody, especially if you are a worker – but as a fix for the inability to further liberalise the WTO the US and the EU started to conclude free-trade agreements with more and more countries. Why do we do that?’

For Kose and Mulabdic at the World Bank the answer is clear. Although global trade can’t make everyone richer, they note that the rapid expansion of trade after the WTO was formed enabled one billion people to escape extreme poverty. ‘It souped up growth in developing economies, enabling many of them to narrow the income gap with wealthier economies’, Kose and Mulabdic write in their blog. ‘During the first decade of this century, per-capita incomes in developing economies grew 3.5 percentage points faster than in developed economies. Trade also sped up the diffusion of technology, contributing to productivity growth’ around the world.

The current problem is that, while a major aim of trade deals is to foster better relations between countries, protectionism and the tension it brings are having the reverse effect and dampening the appetite for trade. Kose and Mulabdic write that ‘misguided populism in many countries is doing serious damage to global trade’. Indeed, an average of just five trade agreements a year have been signed in the 2020s so far – less than half the rate seen in the first decade of the 2000s. Governments’ appetite for trade restrictions, meanwhile, ‘seems insatiable’, write Kose and Mulabdic in their blog, with nearly 3,000 trade restrictions imposed across the world in 2023 – roughly five times the number seen in 2015.

It’s perhaps unsurprising, then, that Bhala says the India-EFTA deal ‘isn’t really a free-trade agreement’ because, while it signifies a softening of Modi’s protectionist stance, it’s drafted in such a way that selective protectionism is allowed to flourish. Indeed, while Modi was clear that he signed the deal in order to create job opportunities for his country’s young people, he has also been careful to ensure that he hasn’t given too much away in order to secure that. Notably, the agriculture sector, which accounts for 41 per cent of employment in India, remains outside the pact’s scope, meaning the country’s farmers don’t have to compete with European imports, nor abide by European quality and safety standards.

‘The Modi administration is very focused on generating employment’, says Bhala. ‘The population of India continues to grow and hundreds of millions of new jobs are needed every year to absorb that. That’s why the India-EFTA agreement isn’t really a free-trade agreement. It protects India in high-employment sectors like agriculture and cars – they don’t want to liberalise those because they need to protect industry and generate jobs.’

A sense of what’s to come

Nevertheless, Bhala says the fact that the Modi administration signed the deal at all – and that it included some key concessions that would have been unimaginable only a few years ago – is a step in the right direction at a time when the climate for international trade is notoriously tough.

New generation international agreements will focus on aspects other than simply negotiating tariffs

Carol Monteiro de Carvalho

Co-Chair, IBA International Trade and Customs Law Committee

‘Chapter 11 of the India-EFTA deal is called Trade and Sustainable Development and if we were having this conversation ten to 15 years ago – even five years ago – India would never have agreed to that’, he says. ‘They always wanted to keep labour, HR [human resources] and the environment out of trade deals because they are vulnerable on that. Now what we see for the first time is not only that they have done a deal with EFTA countries […] but they are through soft law, not hard law, saying that they recognise that trade should be conducted in a sustainable way.’

He adds that while Chapter 11 clearly says that the agreement isn’t intended to harmonise labour or environmental standards, from the perspective of soft law it’s paying attention to the importance of gender equality in the economy and it recognises that the climate crisis is a reality. ‘That’s pretty remarkable; for Indian trade policy that chapter is revolutionary’, says Bhala. ‘We can criticise it for not being hard law, meaning there is no dispute-resolution mechanism, but it’s in the core text of the trade deal and that’s impressive.’

It also gives a sense of what’s to come. Monteiro de Carvalho says that as the international community has ‘failed to prevent international conflicts’, there’s little prospect that the environment in which to negotiate international trade deals will change in the near term. That means ‘so-called new generation international agreements that focus on aspects other than simply negotiating tariffs’ and instead look at matters ‘related to trade facilitation, the environment and social issues’ will become the norm.

Bhala agrees and notes that, as with the India-EFTA agreement, the deals that do come through from now on will probably be either heavily caveated or between countries with similar value systems, or both. He points to the Canada-EU Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement – which despite being agreed in 2014 and provisionally applied in 2017 hasn’t yet been fully ratified due in part to opposition from farmers in France – as the blueprint for what can now be expected.

‘The Canada-EU deal is a good model as they have similar value systems’, he says. ‘On both sides there are similar views on trade-related issues and on linked issues like trade and labour, trade and gender. What can be very contentious and polarising in terms of the culture wars in trade you don’t see in this deal. That means it becomes more of a straight commercial negotiation.’

Bhala adds that while he can see similar deals being signed, he doesn’t believe we’ll see free-trade deals among countries that are competitors. ‘We’re not going to see much advancement of peace through trade – we won’t see countries build relationships or mend relationships through trade agreements. That vision that we saw after the Second World War is gone for now.’

Margaret Taylor is a freelance journalist and can be contacted at mags.taylor@icloud.com