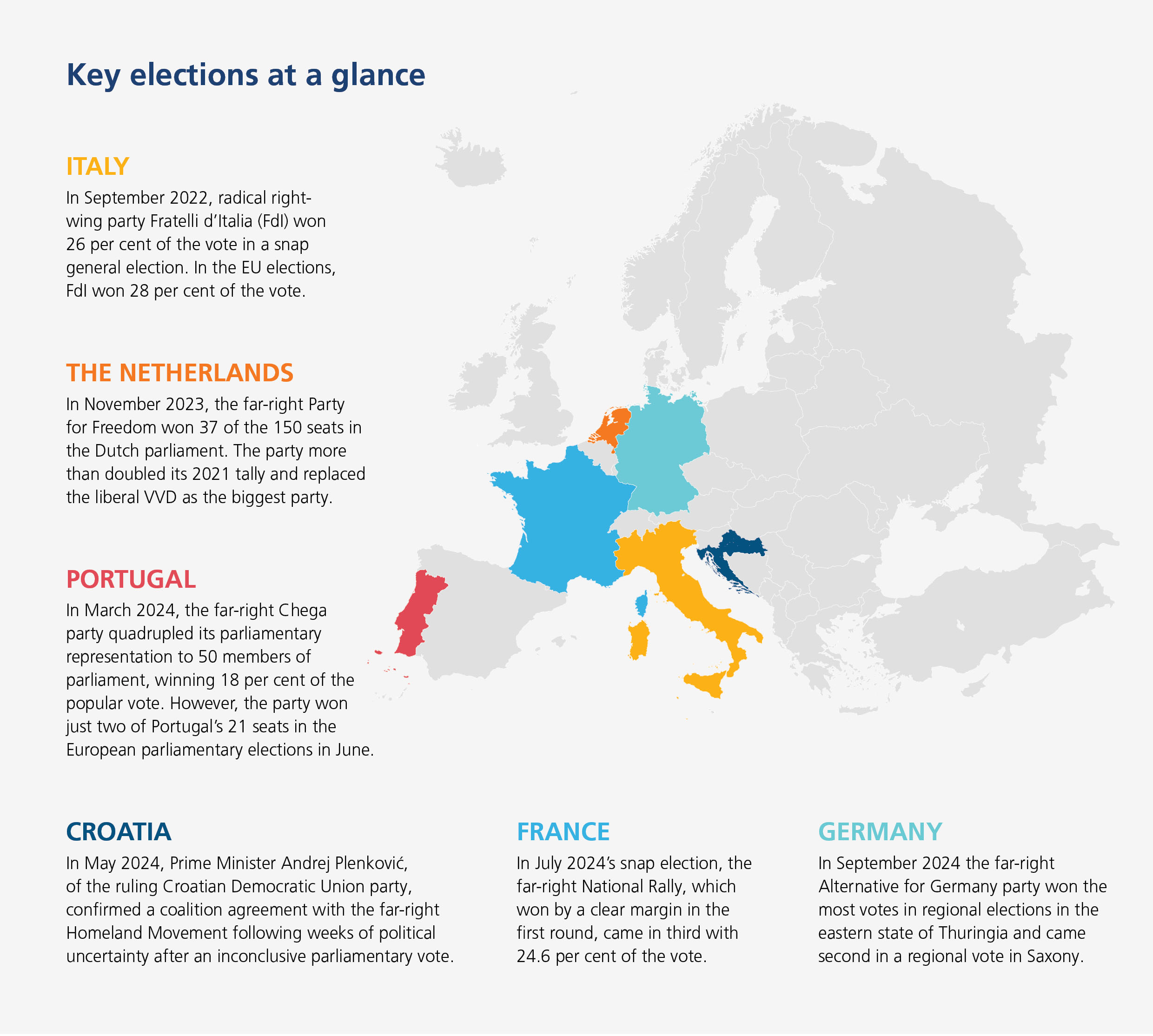

Seven EU Member States – Croatia, the Czech Republic, Finland, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands and Slovakia – now have far-right parties within government. A political party viewed as potentially ‘extremist’ by German authorities has won a state election in Germany. And far-right parties gave strong showings in the summer’s European Parliament elections, prompting a snap national vote in France, which risked National Rally (RN) gaining power.

As the far-right gains support among voters, it’s fast becoming clear that established democracies are facing significant efforts to shrink civic space and erode legal, judicial and democratic checks and balances – with significant implications for the rule of law.

The rise of parties such as France’s RN and Germany’s Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) – given their regressive stance on climate action and immigration, and their overt opposition to sending further aid to Ukraine – has also sparked concern over how such nationalist and xenophobic ideas could gain traction within the political mainstream and affect policy at EU level.

‘There is a connection between the rule of law and the rise of these radical or right-wing ultra-conservative parties’, says Balázs Dénes, Executive Director of the Berlin-based Civil Liberties Union for Europe (Liberties). ‘The steady increase [in popularity] of these parties will eventually have consequences on the rule of law and on human rights and on fundamental freedoms.’

Concerns about the far-right in Europe have taken on particular significance in 2024. In September, the AfD won almost a third of the vote in the eastern German state of Thuringia, marking the first time a far-right party has won in a state parliament election in the country since the Second World War. That same day the AfD came a close second in an election in the neighbouring state of Saxony.

Alternative for Germany (AfD) party leader in Thuringia state Bjoern Hoecke gives thumbs up during an election campaign rally for the upcoming Brandenburg state election in Cottbus, Germany, 19 September 2024. REUTERS/Axel Schmid

These dramatic results came despite a ruling by a German court in May that domestic security services could continue to treat the AfD as a potentially ‘extremist’ party and retain the right to keep the party under surveillance. The Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution – the German domestic intelligence agency – classified the AfD as potentially extreme in 2021. In 2022, a court in Cologne found that the designation was proportionate and didn’t violate the constitution, or European or domestic civil law. The party denies it’s anti-democratic and has said it’ll appeal the ruling, though it can only do so on procedural issues at this point.

Meanwhile, the AfD’s leader in Thuringia, Björn Höcke, has been fined twice in court for using Nazi slogans. He denies knowingly doing so.

The party’s success also represents one of the most prominent recent examples of how far-right parties are striking a chord with younger voters. More than a third of those aged 18–24 voted for the AfD in Thuringia and Saxony.

Hans-Georg Dederer, a constitutional law expert at the University of Passau, says a combination of strong social media and communication skills have helped the party appeal to disaffected younger voters. ‘What is extremely important is that the AfD is very active on social media, especially TikTok, doing by far a much better job than any other of the old democratic parties’, he says. ‘What is more, these old democratic parties now take up issues such as migration [and] internal security [that] have already been consistently addressed by the AfD as pressing issues to be dealt with rapidly – so, what is wrong with the AfD [voters] may ask?’

The party’s successes in eastern Germany echoed the earlier campaign by the AfD in the European Parliament elections in June, where the party’s targeted approach saw it more than triple its share of the youth vote.

Those European Parliament elections represented another political upset for the bloc in 2024, as voters headed to polls in the EU’s first major electoral test since Brexit, the Covid-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Early forecasts indicated that nationalist right and far-right groups could pick up as many as a quarter of the seats. Although their share of the vote wasn’t quite so high, there were significant gains by far-right parties, which only confirmed fears about the direction of the EU Parliament.

In Germany, the AfD came in second ahead of Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s social democratic SPD party, while the far-right Freedom Party gained 25.7 per cent of Austria’s vote. The Fratelli d’Italia (FdI) – a party with neo-fascist roots – gained more than 28 per cent of Italy’s votes, marking a huge victory for the country’s Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, who came to power in 2022. In France, Marine Le Pen’s RN won the popular vote, at 31.4 per cent. Although the RN’s gains were less than some expected, they were still enough to spook President Emmanuel Macron into dissolving parliament and calling a snap election.

Prior to the European Parliament elections, polling indicated that the electorate was increasingly preoccupied by the inability of established parties to manage issues ranging from migration to inflation and the cost of environmental reforms.

In February, Ursula Von der Leyen, who at that point was preparing to seek a second five-year term as President of the European Commission, said she was open to working with political parties that were ‘pro-European, pro-NATO, pro-Ukrainian, clearly supporters of our democratic values’. She criticised the European Parliament group Identity and Democracy – which includes France’s RN and Germany’s AfD – but stopped short of saying she wouldn’t work with the European Conservatives and Reformists group (the ECR), whose membership features Italy’s Fdl and Spain’s far-right Vox party.

This appeared to break with the longstanding cordon sanitaire, whereby mainstream parties refuse to govern in coalition with those holding ‘extreme’ views. In doing so, von der Leyen nudged the door open for a potential working relationship with the ECR.

Normalising the extreme

Susi Dennison, a senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations and leader of the organisation’s European Power programme, says such political rhetoric sets a dangerous tone for the elections. ‘This is very problematic when we talk about the rule of law’, she says. ‘People think about some far-right groups such as [Poland’s Law and Justice Party], which have increased power to the executive and filled the civil service with people of political persuasion […] but we also need to understand the rule of law in the context of minority rights.’

By focusing only on warding off high-level rule of law violations, she says mainstream parties in Europe have often overlooked how far-right policies and rhetoric have progressively normalised the erosion of human rights – particularly of migrants – across Europe. ‘Take Italy as an example’, she says. ‘Some people say [Meloni’s] not as bad as they feared and that she has actually been quite pragmatic and supported broader European efforts etc, but on gender rights in Italy we’re seeing the gradual erosion of progress on abortion. That’s just one example of the tightening environment of protection of rights in Italy.’

In respect of migrants, ‘the challenge that Europe has been grappling with for the past 15 years has been the normalisation of the far right’s agenda to destroy [their] rights’, says Dennison.

In Sweden, this recently came to a head when concerns were raised about a new proposal requiring public sector workers to report undocumented individuals to authorities. The original proposal stemmed from a 2022 agreement among right-wing parties, which led to the formation of the coalition government that relies on the support of the nationalist, anti-immigration Sweden Democrats (SD).

Anne Ramberg, Co-Chair of the IBA’s Human Rights Institute and former Secretary General of the Swedish Bar Association, says the discussions have already provoked controversy, despite not being finalised. ‘The very problem is that the government is completely [dependent] on the support from SD, a party originated from [a neo-Nazi group], in order to stay in power’, she says. ‘The whole idea is of course unacceptable.’

What is concerning is the fact that when repressive proposals are presented people tend to start acting as if the proposals were in effect

Anne Ramberg

Co-Chair, IBA’s Human Rights Institute

Ramberg also voices alarm at how easily far-right polices have become embedded in society even when, as in this case, they haven’t even been signed into law. ‘What also is concerning is the fact that when repressive proposals are presented people tend to start acting as if the proposals were in effect’, she says. ‘A kind of normalisation risk to weaken the resistance.’

In July and August, anti-immigration rhetoric stoked the disorder across parts of England and Northern Ireland in the wake of the killing of three girls in Southport. Online misinformation and anti-immigration sentiment incited targeted attacks on mosques and hotels housing asylum seekers, while social media posts from members of the far right encouraged like-minded individuals to ‘mask up’ and attack dozens of immigration law firms and advice centres.

Mark Stephens CBE, Co-Chair of the IBA’s Human Rights Institute and a partner at Howard Kennedy, says the riots left no doubt that the far right would exploit such tragic events. ‘It does seem that the far right is looking to attack the entire immigration ecosystem and not just illegal people coming in boats’, he says.

Contemplating the unconscionable

In the end, von der Leyen secured the backing of 401 Members of the European Parliament in a secret ballot, comfortably ensuring she’ll spend another five years as European Commission President. Prior to the vote, far-right groups said they were opposed to her re-election. Members of the FdI revealed afterwards that they hadn’t supported her candidacy.

In her acceptance speech, von der Leyen told reporters she would ‘[…] never let the extreme polarisation of our societies become accepted’ and spoke out against ‘demagogues and extremists’ that ‘destroy our European way of life’.

Although the far right’s gains in the European elections fell short of expectations, commentators agree that their performance is worrying in connection to backsliding on the rule of law in the region. ‘European elections are often good bellwethers for what’s going on and what may be expected in national elections’, says Robert Strang, Executive Director of the Central and Eastern European Law Initiative Institute in Prague.

He says the rise of far-right parties in Bulgaria, Hungary and Slovakia is cause for concern. ‘On the other hand’, says Strang, ‘the national elections in Poland last year seem to show the capacity of the democratic system to move in the other direction as well’. Poland’s Law and Justice Party dramatically lost its political majority in the October 2023 parliamentary elections after eight years in power – a period that saw the systematic dismantling of judicial independence, media freedom and civil rights in the country.

Dennison, who lives in France, says far-right parties are increasingly appealing to people at a national level who feel they’re ‘not being listened to’ by mainstream political parties. ‘There have been efforts by parties to co-opt the economic social agenda in addition to the “morality agenda” of the far right’, she says. ‘We’ve seen a lot of growth in support for this in France. The far-right here has no big economic plan, but voters are willing to give it a chance.’

Election posters of the French far-right National Rally (Rassemblement National - RN) party with pictures of their leaders Marine Le Pen and Jordan Bardella are seen near the RN party headquarters before the second round of the early French parliamentary elections, in Paris, France, 5 July 2024. REUTERS/Benoit Tessier

At the end of France’s snap elections in the summer, Le Pen’s RN party ultimately trailed in third place behind Macron’s centrist alliance and the left-wing alliance, the New Popular Front. Le Pen insisted this was ‘a victory postponed’ for her party, and Dennison agrees that observers shouldn’t be too quick to write off far-right groups given the country’s current economic climate and its political impasse. ‘There’s a significant possibility that the RN will win the 2027 presidential election’, she says.

Dissatisfaction with mainstream politics isn’t confined to France and is making previously unconscionable tie-ups much more palatable, says Strang. ‘There are much more aggressive nationalist views that are coming to the surface in far-right parties’, he says. ‘I don’t think it’s about how long you’ve had a working democracy. Instead, it’s, in part, how the economy is doing, because that can put a great deal of stress [on societies]. Immigration does put [on] stress too.’

Although Strang cautions that such pressures have played out differently across Europe – and often resulted in more left-leaning governments – he concedes that discontent has helped Europe become fertile ground for far-right groups. ‘The inflation that societies went through in the last few years, and perhaps the Covid restrictions, however one feels about them, have created much more of a sense of anger and created a lot more energy in the far-right.’

Cautionary tales

In July, German lawmakers became so concerned about the rising popularity of the AfD that they proposed to make several changes to the constitution to protect the country’s highest court – the Federal Constitutional Court (FCC) – from risk of political influence by far-right groups.

The amendment put forward includes enshrining many of the rules that already govern the FCC in the constitution, meaning that a two-thirds parliamentary majority would be required to make any future changes.

Dederer says the proposals could be significant. ‘On the assumption that a right-wing extremist party might get a majority or at least a blocking minority of seats in the Bundestag [the German Parliament], these rules may well prevent the party from capturing the FCC’, he says. ‘For example, the party could not pack the court by electing more than 16 judges or by establishing a third senate. [The] blocking of the election of a new judge would not make the court dysfunctional because the old judge would still be in office.’

The instincts of populist movements make the judiciary a natural target for their attacks because judges absolutely represent what would be perceived as elitist

Robert Strang

Executive Director, Central and Eastern European Law Initiative Institute

Dederer believes the thinking of German lawmakers may have been influenced by recent efforts to undermine the judiciary elsewhere in Europe. ‘This is what happened after right-wing extremist/populist parties came to power in Poland and Hungary’, he says. The constitutional courts of both states were packed by partisans of the then-ruling party in Poland, the Law and Justice Party, and of Fidesz in Hungary, respectively. ‘Hence, the impartiality and independence of these courts cannot be considered to be guaranteed any longer’, explains Dederer.

Ramberg praises the German government’s proposals and says there’s been similar discussions taking place in Sweden where concerns have also been raised about ‘the weak protection of the independence of the judiciary’.

Strang also welcomes the development. He highlights that the constitutional court in some jurisdictions has been the path for attacks against the judiciary. ‘The instincts of such populist movements make the judiciary a natural target for their attacks because judges absolutely represent what would be perceived as elitist’, he says. ‘They’re making rulings that are against what parliament might be doing and therefore might be seen as anti-majoritarian in that approach, even though, in fact, what they’re doing is securing individual rights against the state.’

Although the centre-right grouping scored the most seats in the European Parliament elections, keen observers won’t have failed to notice the irony of Hungary assuming the mantle of the EU’s rotating six-month presidency just weeks later in July. The country’s governing Fidesz party was forced to quit the centre-right European People’s Party grouping in 2021 amid concerns over democratic backsliding, which Fidesz’s leaders refute.

Democracy is a fragile system. One solution is the strengthening of civil society and investing in political education and the promotion of democracy

Balázs Dénes

Executive Director, Civil Liberties Union for Europe

Dénes, who is Hungarian but has lived in Germany for seven years, hopes his motherland’s decline will act as a cautionary tale for other countries in Europe that are being swayed by far-right groups. ‘What is happening to Hungary is extremely sad and worrying, but it could also hold some takeaways for other countries’, he says. ‘One potential takeaway is that democracy is a fragile system. One solution is the strengthening of civil society and investing in political education and the promotion of democracy. That’s something the European Union could be doing much better than it is doing now.’

As support grows for far-right groups among young voters, it’s imperative that people understand that when democracy is at risk, we all suffer. ‘It's not about telling people what they should think’, says Dénes, ‘but it is about making sure that every new generation understands that freedom, justice and equality in front of the law is important, and that the discrimination of certain citizens and certain groups is a bad thing and will only result in less economic prosperity in the long term. If the quality of democracy declines that will eventually be followed by the decline of economic growth. Economic growth is practically impossible without a free and fair society’.

Ruth Green is a freelance journalist and can be contacted at ruthsineadgreen@gmail.com