The year of elections: The US election and Mueller’s legacy

William Roberts, IBA US CorrespondentThursday 3 October 2024

Robert Mueller’s investigation into interference in the election that saw Donald Trump become President offered shocking revelations. Global Insight assesses whether enough has been done to learn the lessons and protect US democracy.

A leading US presidential candidate takes a stance on war in Europe that leaves Western allies unsettled. Intelligence agencies warn Moscow is spreading divisive messages to Americans on social media. Counterintelligence agencies report a foreign adversary has hacked computer files from US political campaigns.

The news headlines of the US presidential campaign in 2024 are eerily similar to those of 2016 when Donald Trump, a reality TV personality, shocked the country and won the White House. What’s changed after four years of Trump’s presidency – and four more years of legal trials and controversy surrounding him – is that the stakes in this November’s election are higher.

Never has a major party candidate been so heavily investigated, beginning with Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation in 2017–2019. Donald Trump now faces four criminal trials, on allegations he denies, which are on hold because he’s running for President again. Should Trump win the election, most of those legal problems will go away. If not, his alleged criminal conduct will probably catch up with him, former US prosecutors and defence lawyers tell Global Insight. ‘It’s a remarkable moment’ for the rule of law in the US, says Matt Kaiser, Senior Vice Chair of the IBA Criminal Law Committee and a partner at law firm Kaiser in Washington, DC.

This has been a stressful time for our democracy. But I don’t think we’ve failed. We could yet fail, but I’m hopeful that we won’t

Matt Kaiser

Senior Vice-Chair, IBA Criminal Law Committee

‘There’s a temptation to look at what’s happening as like a net under a circus performer, that the net has broken, and the performer [US democracy] has fallen to the ground’, says Kaiser. ‘That's not quite right. The net’s frayed. This has been a stressful time for our democracy. But I don’t think we've failed. We could yet fail, but I'm hopeful that we won’t.’

Trump’s conduct since bursting onto the political scene has tested US institutions and norms, the courts, the media and civil society. Beginning with the Mueller investigation, which proved to be a defining chapter in Trump’s presidency.

Appointed by the US Department of Justice (DOJ) to conduct an independent investigation into the President and Russia’s interference in the 2016 presidential election, Robert Mueller was a renowned DOJ prosecutor and a well-respected former head of the FBI.

Mueller and his team documented influence campaigns and cyber-attacks by Russian agents. Further, the investigation found the Trump campaign was aware of and welcomed Russia’s help. Nevertheless, Mueller didn’t find a ‘smoking gun’: incontrovertible incriminating evidence that showed Trump had engaged in a conspiracy with Russian agents.

Caught in the Crossfire

Back in July 2016, as the presidential campaign was getting underway in earnest, an uproar erupted over leaked Democratic Party emails. Trump’s opponent, Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton, had faced criticism for using a private email server while she was Secretary of State, meaning some 30,000 emails weren’t preserved in government records. The FBI eventually said she shouldn’t face criminal charges.

Former Special Counsel Robert Mueller testifies before a House Judiciary Committee hearing on the Office of Special Counsel's Investigation into Russian Interference in the 2016 Presidential Election on Capitol Hill in Washington, DC, 24 July 2019. REUTERS/Jonathan Ernst

Amid this controversy, as Mueller would later reveal, Russian agents hacked email accounts of people in Clinton’s campaign and the Democratic Party. They released troves of embarrassing messages through front groups ‘Guccifer 2.0’ and ‘DCLeaks.com’, as well as WikiLeaks.

Amid this, Trump openly urged the Kremlin to hack and release Clinton’s emails. ‘Russia, if you are listening, I hope you’re able to find the thirty thousand emails that are missing. I think you will probably be mightily rewarded by our press’, Trump said at a press conference.

The comment sent shockwaves through the US political system. Counterintelligence agencies were already scrambling to track down the Russian hackers. It’s not only bad form to solicit a foreign cyberattack on a political rival – it’s illegal under US campaign finance law to accept assistance from other countries.

Meanwhile, the FBI was already working on a tip from an Australian diplomat that Trump foreign policy adviser George Papadopoulos had gossiped at a London bar about the Kremlin hacking emails and planning to release ‘dirt’ on Clinton. Days later, the FBI opened a formal investigation dubbed ‘Crossfire Hurricane’ into whether Trump’s campaign was coordinating with Russian agents. It was this inquiry that would become the Mueller investigation.

One of the foundational principles of democratic governance is that no person is above the law, not even the elected head of state. While political and legal contexts vary, a common characteristic of modern democracies is the impulse to hold elected leaders accountable, although it’s often challenging.

If democracy and the rule of law is not respected in Western democracies, there are limited prospects to influence other countries to adhere to these principles

Anne Ramberg

Co-Chair, IBA’s Human Rights Institute

‘Accountability is a pillar in a democracy and the rule of law’, says Anne Ramberg, Co-Chair of the IBA’s Human Rights Institute and a former Secretary General of the Swedish Bar Association. ‘The US claims to be the largest democracy in the world. When democratic principles are set aside, the confidence in the system is undermined.’ And, ‘if democracy and the rule of law is not respected in Western democracies, there are limited prospects to influence other countries to adhere to these principles’, Ramberg says.

Michael H Huneke is a partner at Hughes Hubbard & Reed in Washington, DC and Website Officer on the IBA Anti-Corruption Committee. ‘Whether it’s the Mueller report, whether it’s the recent Supreme Court [judgments], the justice system has a very limited effectiveness in actually policing bad political behaviour, especially when behaviour becomes unmoored from norms’, says Huneke. ‘We have a candidate in former President Trump, who’s very overt, and frankly transparent about the way he will say whatever he thinks he wants to say, not really respecting norms or ways of engaging in political dialogue or debate.’

‘This Russian thing’

A primary focus of Mueller’s investigation was Trump’s obstruction of the FBI’s earlier Russia inquiry. One of the targets of Crossfire Hurricane had been former Army General Michael Flynn, who had advised the Trump campaign on foreign policy.

Still in office, President Barack Obama had imposed sanctions on Russia in December 2016 for its underhand election meddling. Trump and his team were worried that Russian President Vladimir Putin would retaliate in kind, setting back Trump’s hopes for warmer ties with Moscow. He dispatched Flynn to meet with Russian Ambassador Sergey Kislyak.

Flynn later lied to FBI agents and others about those contacts. Trump named him National Security Adviser, a highly sensitive White House position. As the FBI closed in, Flynn was forced to resign.

A few months later in the White House as president, Trump held a one-on-one meeting with then FBI Director James Comey in a bid to quell what Trump called ‘this Russia thing’. According to Comey’s notes from the time, Trump asked him to go easy on Flynn, and also wanted Comey to say publicly that Trump was not a target of the investigation. When Comey refused, Trump dismissed him. For his part, Trump denies asking Comey for his loyalty and claimed the then FBI Director had told him he wasn’t a target of the investigation, which Comey later denied.

The next day, Trump hosted Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov and Ambassador Kislyak in the Oval Office. An official Russian photographer captured images of the three men smiling and laughing during the meeting. ‘I just fired the head of the FBI’, Trump boasted to his Russian visitors, according to a White House memorandum of the meeting. ‘I faced great pressure because of Russia. That’s taken off’, Trump said.

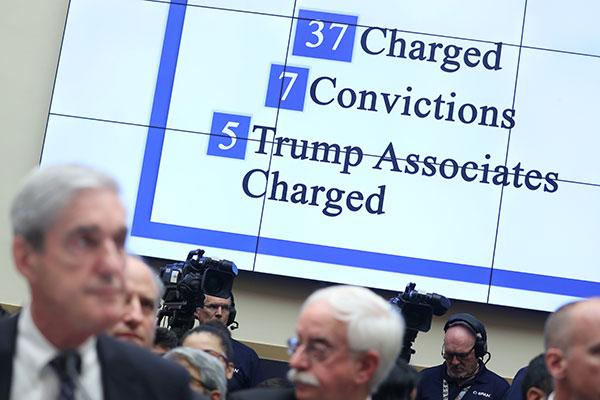

Former Special Counsel Robert Mueller testifies before a House Judiciary Committee hearing on the Office of Special Counsel's Investigation into Russian Interference in the 2016 Presidential Election, as a graphic on a screen behind him shows the results of his investigations, on Capitol Hill in Washington, DC, 24 July 2019. REUTERS/Jonathan Ernst

But Trump was wrong. His abrupt firing of Comey and shifting explanations ignited a political uproar in Congress. Both Democrats and Republicans called for appointment of a special counsel. ‘It’s difficult to appreciate today, with all of the hindsight and political rhetoric that’s gone on about it, just what a crisis the folks at [the] DOJ were confronting’, explains Shanlon Wu, a former DOJ official and federal prosecutor now in private practice at McGlinchey Stafford in Washington, DC.

‘They had these allegations that the at-the-time candidate and then the actual elected president might have had connections to a foreign government, Russia’, Wu says. ‘The amount of pressure they were under and the amount of crisis management they had to do was enormous.’

Enter Mueller

Mueller was appointed by Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein, a career federal prosecutor, because US Attorney General (AG) Jeff Sessions had been part of Trump’s political campaign. Sessions had recused himself from the investigation after it was revealed he too had met with Kislyak during the campaign.

Under DOJ regulations, the Office of Special Counsel is designed to be independent from the political pressures that come from the White House and elsewhere. But it’s an imperfect structure. Special counsels still report through the DOJ’s chain of command up to the AG, who in turn is appointed by and beholden to the president.

Mueller was seen as an excellent choice, having led the FBI capably for 12 years in the difficult period after the 2001 Al-Qaeda attacks. There was bipartisan confidence in his ability to handle the matter fairly.

But Trump publicly criticised Sessions as ‘scared stiff and missing in action’ for refusing to stop what Trump called a ‘Rigged Witch Hunt’. He eventually dismissed Sessions in autumn 2018 in an incident that drew comparisons to President Richard Nixon’s ham-fisted attempt to quash the Watergate investigation in 1973, which eventually led to his resignation.

Mueller’s investigation would last 22 months. It never escaped the divisive politics that attached to it. To this day, Trump’s supporters view it as a partisan weaponisation of the DOJ by powerful Democrats who wanted to take Trump down. People who oppose Trump see it through the opposite lens as a legitimate and necessary law enforcement inquiry that unearthed clear evidence that Trump’s campaign welcomed Russian interference.

Mueller found that Trump’s campaign manager Paul Manafort, son Donald Trump Jr and son-in-law Jared Kushner met at Trump Tower in New York with Russian lawyer Natalia Veselnitskaya in June 2016. She was asking that Trump, if elected, lift the US Magnitsky Act sanctions on Russia. Emails showed Donald Jr had taken the meeting expecting to be offered dirt on Clinton. He later issued an evasive explanation, directed by his father, claiming the meeting was about Russian adoptions. Veselnitskaya’s Russian translator told Mueller’s FBI agents that this wasn’t the whole story.

Two months later, Manafort and deputy campaign manager Rick Gates met with a longtime business associate, Konstantin Kilimnik, whom the FBI has assessed was connected to Russian intelligence, according to the Mueller investigation. They talked about Trump’s campaign and internal poll numbers, which Manafort and Gates had been sharing with Kilimnik.

Mueller’s team also uncovered detailed evidence that a company it terms a Russian ‘troll farm’, the Internet Research Agency, based in St Petersburg, was using social media platforms to promote Trump’s candidacy. The operation was funded by Yevgeny Prigozhin, a Putin ally and the founder of the mercenary Wagner Group, who would later rebel against Putin’s conduct of the war in Ukraine and die in a plane crash.

Mueller documented various attempts by Trump to obstruct the investigation. The former president repeatedly attempted to fire Mueller and shut the investigation down but was saved by the inaction of his White House chief counsel and top staff, who understood what the consequences would be. Still, knowing that the DOJ’s internal policy wouldn’t allow a criminal indictment of a sitting President, Trump and his allies dangled pardons for people Mueller’s prosecutors were targeting, while the President used social media posts to denigrate people who cooperated with Mueller and praise those who didn’t.

Courts play an important role in the checks and balances of the US Constitution, but in the case of a President who’s willing to use his pardon power to subvert the process, they’re impotent. ‘Courts move incredibly slowly’, says Kaiser. ‘And much of their work is off camera. Our media environment moves incredibly quickly. Courts are ill-equipped to respond to those pressures from our media, our news cycle, especially as it relates to politics.’

Eventually, Manafort, Flynn and campaign adviser Roger Stone received pardons from Trump. Gates, who had cooperated with Mueller’s prosecutors, didn’t.

Trump emboldened

In March 2019, Mueller’s team delivered a voluminous 448-page report to US Attorney General William Barr. It identified ten instances of possible obstruction of justice by Trump. While Mueller stopped short of asserting that Trump had obstructed justice, he also didn’t clear Trump of criminal wrongdoing. Instead, the report lays out facts and legal analysis, leaving it to Congress and others to make judgements.

Glenn Kirschner, a former DOJ prosecutor who worked with Mueller in Washington, DC’s homicide division, believes that the Mueller report was clear enough. ‘I got to see firsthand, in great detail the investigative work of Bob Mueller, both in and out of the grand jury. So, I know what an extraordinary, thorough, meticulous and aggressive investigator Bob Mueller is’, says Kirschner.

Two days after Mueller’s report was delivered, Barr issued a four-page summary. Barr’s letter said the Attorney General had determined the evidence didn’t show that Trump had committed obstruction of justice, and neither was Trump involved in any crime related to Russia’s interference in the election.

‘That letter was a shot across the bow, signalling that the short interregnum of the rule of law represented by Mueller was over’, wrote Andrew Weissman, one of Mueller’s lead prosecutors, in his book Where Law Ends: Inside the Mueller Investigation, published in 2020. ‘The checking function Mueller provided on the actions of the president had come to an abrupt end at the Department of Justice and the White House.’

It would be weeks before Congress and the public were able to see what Mueller actually found. Meanwhile, Barr doubled down on his mischaracterisation of the report with a press conference when it was released to Congress.

‘If we had had confidence that the president clearly didn’t commit a crime, we would have said so. We did not, however, make a determination as to whether the president did commit a crime’, Mueller said at a remarkable press conference in May 2019, in which he rebutted both Trump and Barr’s characterisations of the report. The report ‘speaks for itself’, Mueller said. Later in testimony to Congress, Mueller said Trump ‘was not exculpated’.

Within days of the Mueller report’s release to Congress and Barr’s dismissal of its findings, Trump held a phone call from the Oval Office with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky. He was withholding Javelin antitank missiles from Kyiv allegedly to pressure Zelensky to announce a sham investigation of then former Vice President Joe Biden, pressure both men would deny. A whistleblower raised the alarm in Congress and Trump would be impeached for a matter he described as a ‘witch hunt’.

It's important as lawyers that we lead in our communities, in discussing how the rule of law has endured and will endure

Deborah Enix-Ross

Former Vice Chair, IBA Bar Issues Commission

‘The investigation ultimately emboldened Trump’, Gates wrote in his 2020 memoir titled Wicked Game: An Insider’s Story on How Trump Won, Mueller Failed and America Lost. ‘It gave Trump even more power to continue to fight, to push back, to create and exploit chaos in an already unstable political environment, to upend the norms and protocols in Washington, and to solidify his support not only with his large base but with more and more Republicans inside the Beltway.’ As to the Mueller investigation: ‘They never found what they were looking for – because it wasn’t there’.. (Emphasis his in both instances.)

Trump moved on from his first impeachment to falsely claiming that the 2020 election – which he lost – was stolen. Later, a violent mob stormed the US Capitol on 6 January 2021 in an attempt to block Congress from certifying Biden’s election win. Trump now faces criminal fraud and conspiracy charges in federal and state courts stemming from those events – charges he denies.

Should Trump get re-elected, he would have the authority to order dismissal of the two federal cases pending against him without any further questions. And he’d be substantially insulated from any state proceedings. In campaign speeches, Trump has overtly threatened to use the justice system to prosecute his political enemies. He’s even said he’ll bring charges against local election officials and members of the media.

‘If he is elected, who is going to become Attorney General of the United States for Donald Trump?’ asks Gene Rossi, a former federal prosecutor who’s now in private practice at Carlton Fields in Washington, DC. ‘They will be fired in a New York minute, if they even dare to say, “I can't do this” to Donald Trump. That scares the hell out of me!’ he says.

Adding to the uncertainty, the Supreme Court ruled in July that Trump enjoys broad immunity for his official acts as President. Under this new standard, Mueller’s investigation for obstruction couldn’t have been triggered by the President’s firing of FBI Director Comey – it was an official act.

‘There’s no doubt that we are seeing a challenge to the understanding of the rule of law’, says Deborah Enix-Ross, a former Vice Chair of the IBA Bar Issues Commission and a senior advisor to the International Dispute Resolution Group at Debevoise & Plimpton in New York.

The Mueller investigation and the subsequent impeachments and criminal cases brought against the former President have been a ‘shock’ and sparked ‘more discussion about the rules and the importance of maintaining the rules’, she says. If Trump wins the US election ‘we will be in uncharted territory, with respect to the disposition of his criminal cases’.

At the same time, Enix-Ross is optimistic about the future. ‘We have a legal system and we are adhering to that system, although for some people it may not be satisfactory in this moment. But it is a long process and, in the end – most of the time – our legal system gets it right’, she says.

‘It's important as lawyers that we lead in our communities, in discussing how the rule of law has endured and will endure even when there are decisions where we don’t agree with the outcome’, she adds. ‘We will get through this, and we will come out stronger because of it.’

Acting on Mueller’s legacy

Mueller’s report set off a cascade of hearings and legislative activity in Congress. Three months after releasing his report, Mueller testified before the House of Representatives Judiciary and Intelligence committees. There was debate about moving forward with articles of impeachment against Trump for obstruction of justice. But Democrats who controlled the House instead launched an impeachment inquiry into Trump’s alleged attempt to pressure Ukraine in exchange for political dirt on Biden.

Mueller exposed the need for better safeguards for election infrastructure in the US and guardrails against disinformation campaigns on social media. Congress took up but failed – amid partisan disputes – to pass several bills aimed at securing US elections. However, since the 2016 election, Congress has provided $955m in grants to states to improve computer and data security. In 2022, with an eye on preventing the events leading up to the 6 January attack on the Capitol from happening again, Congress passed reforms to the Electoral College process to clarify how electoral votes are cast and counted and to resolve possible weaknesses in the law, among other things.

In response to the threats of foreign interference highlighted by Mueller, the FBI and partner agencies took steps to protect election systems and counter online disinformation. These included working with state and local officials to improve election security where it matters most.

But the threats continue. In August, the agencies warned that Iran had hacked Trump’s campaign and was seeking to ‘stoke discord and undermine confidence’ in US democratic institutions. In September, the DOJ announced the US government had seized 32 web domains and indicted two employees of Russia’s state-run propaganda outlet RT allegedly engaged in a disinformation campaign to influence the 2024 election. We may be about to find out whether the net protecting US democracy is only a little frayed or whether it has been so badly damaged that US democracy could come crashing to the ground.

William Roberts is a US-based journalist and can be contacted at wroberts3@me.com

Header pic: Former Special Counsel Robert Mueller testifies before the House Intelligence Committee at a hearing on the Office of Special Counsel's Investigation into Russian Interference in the 2016 Presidential Election on Capitol Hill in Washington, DC, 24 July 2019. REUTERS/Leah Millis