The global assault on rule of law

Anne McMillanWednesday 14 September 2022

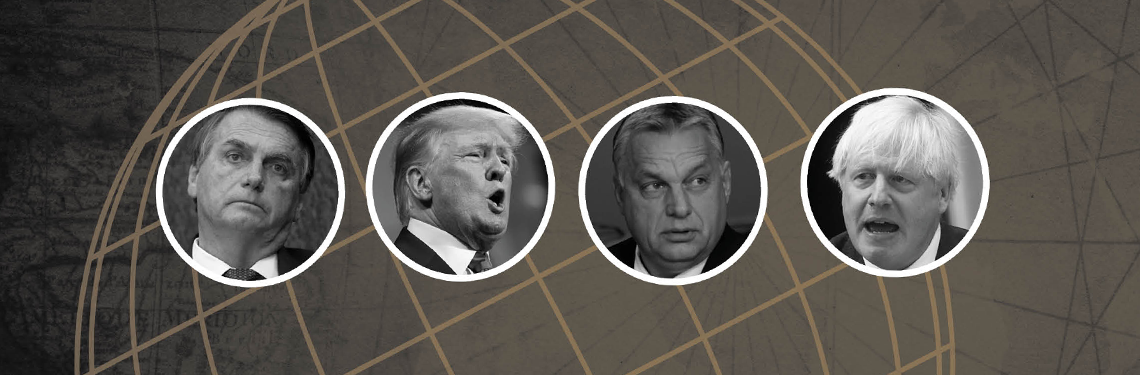

By attacking the independence of the judiciary, populist political leaders around the world are undermining fundamental aspects of democracy and civilised society. If it continues unchecked, the consequences will be devastating.

Former British Prime Minister and champion of neoliberalism, Margaret Thatcher, once declared: ‘The legal system we have and the rule of law are far more responsible for our traditional liberties than any system of one man one vote. Any country or government which wants to proceed towards tyranny starts to undermine legal rights and undermine the law.’

Had Thatcher, herself a member of the Bar of England and Wales, uttered these words in 2022, she would have risked being labelled by her political heirs in the current Conservative government as a ‘lefty lawyer’, an epithet applied by some to lawyers who have recently challenged government decisions. Indeed, the United Kingdom, a country often described as spawning the ‘mother of parliaments’, has apparently reached the point where lawyers doing their job can be ridiculed by a Prime Minister.

Any country or government which wants to proceed towards tyranny starts to undermine legal rights and undermine the law

Baroness Margaret Thatcher

UK Prime Minister, 1979–1990

One of Thatcher’s more recent successors as prime minister, Boris Johnson, has derided lawyers considered hostile to his aims as ‘lefty human rights lawyers and other do-gooders’. When faced with legitimate legal challenges to a UK government policy of sending asylum seekers to Rwanda for processing (and eventual settlement), Johnson even went so far as to infer that the representing lawyers were ‘abetting the criminal gangs’ who had trafficked people. Following these comments Mark Fenhalls KC, Chair of the UK Bar Council, noted that some lawyers had received death threats.

A warning of tyranny

Stephen Denyer, Director of Strategic Relationships at the Law Society of England and Wales, and Co-Chair of the IBA Rule of Law Forum, warns that such attacks by politicians, particularly when spread by the media, have serious ramifications. ‘It is misleading and dangerous for government ministers to suggest that it is wrong for them to be held to account for their actions by a legal system that, in a democracy, exists to do just that. Attacks like this, from the highest politicians in the land, undermine the rule of law and can have real-life consequences. They may also weaken public trust in the justice system.’

Denyer further notes the chilling effect this may have on individual lawyers working on cases deemed ‘undesirable’ by the government: ‘Solicitors working in politically sensitive areas such as immigration and asylum are dedicated professionals who remain committed to the best interests of their clients. We are however aware that some of our members who work in these areas may nowadays be more likely to decline to speak publicly about their work because of the political climate and the way such issues are reported by some UK media outlets.’

Even so, lawyers are not the ultimate arbiters and thus greater government ire seems to be reserved for judges. In 2021, then UK Justice Secretary and Deputy Prime Minister Dominic Raab called in an interview with UK newspaper The Telegraph for a ‘mechanism’ to be created which would enable judgments of UK courts to be ‘corrected’ by ‘ad hoc legislation’ whenever ministers deem these judgments to be ‘incorrect’.

Considering Parliament can change legislation whenever it wants, concerned constitutional experts speculated whether Raab’s words were meant to imply that government ministers, rather than the legislature, might override judicial decisions. Raab’s repeated use of the misleading and erroneous expression ‘judicial legislation’ in his interview helped create the impression that the government feels the judiciary is trying to usurp the role of Parliament. Perhaps the government hopes simply floating ideas like these will make judges think twice in their judgments.

Foreign judges also appear to antagonise the government. A 2022 government proposal for a new UK ‘Bill of Rights’ aims to scrap the current requirement in UK domestic law for courts to ‘take into account’ decisions of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). The idea, often mentioned by ministers, that domestic judgments should always reign supreme in the UK has been widely reported by the media, though generally without any clear explanation of what is being proposed by the government, nor its legal implications.

The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), which came into force in 1953, obliges States Parties such as the UK to abide by decisions of the ECtHR. Any UK domestic legislation purporting to ‘alter’ this requirement would do nothing to change the country’s obligations under international law. Indeed, it could push the UK even further into conflict with international law, with the likelihood that more cases will be challenged, and potentially overruled, at the ECtHR. In reality, the only way for the government to legally disregard the rulings of the ECtHR would be to withdraw from the Convention itself.

What is the purpose of a proposal that makes no sense legally? Mark Elliott, Professor of Public Law at Cambridge University, refers to these ideas as part of an ‘executive power project’ aimed at undermining constitutional checks and balances which should be called out. ‘Even in a post-truth age, such constitutional gaslighting cannot be allowed to go unchallenged’, he says.

Judicial independence under threat

The UK experience is not unique. The fact that international law overrides national law – notably that signed treaties must be adhered to – is also being challenged in Poland in a process which highlights another problem: judicial impartiality. Poland’s Constitutional Court (widely seen to have lost its independence from the executive following government interference in judicial appointments) recently ruled that the Polish Constitution prevails if it is incompatible with EU law. This view has been firmly rejected by the Court of Justice of the European Union.

Another EU State has a similar problem. In 2020 András Zs Varga was elected as head of the Hungarian Supreme Court by the country’s parliament, despite strong opposition from the judges’ self-governing body, the National Judicial Council, which was concerned, among other things, about his lack of judicial experience. The UN Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers told the Hungarian government that Varga’s ‘appointment may be regarded as an attack to [sic] the independence of the judiciary and as an attempt to submit the judiciary to the will of the legislative branch, in violation of the principle of separation of powers’. Against a background of mounting EU criticism of the Hungarian government’s politically motivated interference in the judiciary, Varga has described the EU’s interpretation of the rule of law as ‘tyrannical’ and ‘totalitarian’.

Because it is important that the judiciary remains independent, and is seen to be so, political appointments of judges clearly undermine the legitimacy of the judiciary wherever they occur. The role of the US President in the appointment of judges to the Supreme Court is an example of a significant democratic weakness which threatens to feed assumptions that the judiciary is a politicised body. As Richard Goldstone, former justice of South Africa’s Constitutional Court and Honorary President of the IBA’s Human Rights Institute, says: ‘The rule of law requires judges, in fact and in perception, to be independent of the political system and especially political parties. The US system has failed in this respect. Judges are tarred from the day they are appointed.’

UK barrister and constitutional law expert Dr Sam Fowles points out: ‘There is a difference between judges involving themselves in politics and judges making legal decisions which have political impact.’ But it is a distinction that the public will find hard to make when politicians control judicial appointments.

System breakdown and violence

Undermining the rule of law has become a ‘go-to’ strategy for populist leaders, even in a well-established democracy like the US. The 6 January attack on the US Capitol took the threat to the democratic system beyond rhetoric to a deadly level and led to charges of ‘seditious conspiracy’ against members of extreme right-wing groups alleged to have been the attack’s leaders.

Recent US Senate Committee hearings regarding the attack have revealed alarming details of the extent to which then US President Donald Trump fomented – or at least made no attempt to stop – the violence on that day. Trump had also urged an election official in the state of Georgia to overturn election results and tried to persuade then Vice-President Pence to reject the legitimate presidential election results in Congress. A key to Trump’s attitude to the law might be found in the words of his long-time personal attorney, Roy Cohn (former chief counsel to US Senator Joseph McCarthy during his notorious witch hunt of alleged communists in the 1950s), who famously said: ‘I don’t want to know what the law is, I want to know who the judge is.’

Trump is now the target of multiple legal actions, ranging from tax offences and fraudulent business conduct to interference with elections. The latest action by the FBI in searching Trump’s personal residence and seizing classified and other documents, which it claims were illegally retained when Trump’s presidency ended, has been used as a catalyst to ramp up fundraising for Trump and the Republican Party. Trump predictably turned on the FBI, ironically claiming its attempts to retrieve documents are politically motivated: ‘Law enforcement is a shield that protects Americans. It cannot be used as a weapon for political purposes.’

It’s misleading and dangerous for government ministers to suggest that it is wrong for them to be held to account for their actions by a legal system that, in a democracy, exists to do just that

Stephen Denyer

Co-Chair, IBA Rule of Law Forum

Trump’s attacks have gone beyond the FBI to include the judiciary, election workers, the police and the civil service, suggesting that the whole system is corrupt or politically motivated against him. When members of the public start to believe this narrative it can have dangerous consequences. Following the FBI raid on Trump’s residence, the federal judge who approved the warrant, Bruce Reinhart, has been subject to death threats on social media: ‘“This is the piece of shit judge who approved FBI’s raid on Mar-a-Lago”, a user wrote on a pro-Trump message board. “I see a rope around his neck.”’

More broadly, it now seems that a large proportion of the US public believe that effective leadership may require overriding inconvenient rule of law principles. A 2022 survey by the University of California, entitled Views of American Democracy and Society and Support for Political Violence, found that over 40 per cent of Americans agree that ‘having a strong leader for America is more important than having a democracy’.

This trend bodes ill for the future. In December 2021 three retired US generals – noting the ‘disturbing number of veterans and active-duty members of the military’ who took part in the attack on the Capitol –warned of the ‘potential for lethal chaos inside our military’ if the result of the 2024 presidential election is challenged. This view of possible impending violence is borne out by another finding from the University of California survey, namely that 50.1 per cent of Americans believe that ‘in the next few years there will be a civil war in the US’, suggesting many have lost faith in the resolution of differences within existing democratic structures.

So why are sections of the electorate swallowing blatant untruths that subvert the rule of law in democracies, both young and old? In part, the answer lies with those bearing the message.

Media manipulation

According to 2022 figures, Fox News is the most watched cable news network in the US. The channel has been notorious for disregarding facts while acting as a propaganda tool for Trump. In the UK, widely read newspapers such as the Daily Mail perform similar functions.

Following a UK High Court decision in 2016 perceived by the government as obstructing its policy in achieving Brexit, the UK tabloid ran an inflammatory headline on its front page: next to a photograph of the three High Court justices involved were the words ‘Enemies of the People’. Goldstone acknowledges that judges need thick skins but thinks this headline goes too far: ‘The tabloid headline goes beyond what is acceptable, and political and judicial leaders should both respond to such clearly unacceptable attacks that are calculated to tarnish the judiciary and threaten the independence of the judges. Where the line is crossed is often difficult to define and the right of free speech should be given a wide margin of appreciation.’

The Lord Chancellor and Justice Minister at the time (now UK Prime Minister), Liz Truss, initially balked at defending the judiciary, eventually responding with generalities. Justice McAlinden, judge of the High Court of Northern Ireland and Membership Officer of the IBA Judges Forum, notes that there is a statutory duty for ministers, in particular the Lord Chancellor, to actively defend judicial independence:

‘The Constitutional Reform Act 2005 […] imposes enhanced positive duties on the Lord Chancellor who is charged with defending the independence of the judiciary and who solemnly undertakes to do so in the oath of office. The Lord Chancellor should be able to rein in colleagues who occasionally say things that sit uneasily with the rule of law or judicial independence and in this way the Lord Chancellor remains the guardian of judicial institutional independence.’

The newspaper headline had direct consequences, with the Lord Chief Justice at the time, John Thomas, writing to Truss to tell her that some judges had expressed concerns because litigants in person had repeated to them the accusation: ‘you’re an enemy of the people’. The President of the UK’s Supreme Court, Lord Neuberger, commented of the government’s response at the time: ‘After the [High] Court hearing, I think they could have been quicker and clearer. But we all learn by experience […]’.

But do we really? In 2022 an All-Party Parliamentary Group report (entitled An Independent Judiciary – Challenges Since 2016) found that UK ministers ‘have, from a constitutional perspective, acted improperly in attacking judges, and in particular doing so in a way that might reduce public confidence in the judiciary’. The report supported the findings of two independent reviews that there was ‘no persuasive evidence’ to justify accusations by politicians and the media that judges had interfered in politics.

In Poland, the media has also been key in distorting the public view of the judiciary. According to Mikołaj Pietrzak, Dean of the Warsaw Bar Association, it played a key role in ensuring the re-election of the ruling right-wing populist PiS Party (ironically, the letters stand for ‘Law and Justice’ in Polish) in 2019 despite its persistent attempts to undermine the rule of law. ‘One of the important factors that made this possible was the transformation of the public state media into a government-controlled instrument of propaganda’, says Pietrzak. ‘Many Poles still rely on the state media as their exclusive source of information about public affairs […] Even in the best of circumstances such fundamental constitutional concepts such as the rule of law, independence of the judiciary and the balance of the powers can be difficult for the public to understand.’

Internationally, the subversion of judicial decisions seems to span the political spectrum and involve those on the left as well as the right. While the US Supreme Court was hearing arguments in a major abortion case which subsequently overturned Roe v Wade and limited abortion rights, the Democratic Party’s Senate Majority Leader Charles ‘Chuck’ Schumer said of the presiding judges: ‘I want to tell you [Justice] Gorsuch, I want to tell you [Justice] Kavanaugh – you have released the whirlwind and you will pay the price. You won’t know what hit you if you go forward with these awful decisions.’

Although Schumer later withdrew the statement, it led to US Chief Justice John Roberts, responding: ‘Justices know that criticism comes with the territory, but threatening statements of this sort from the highest levels of government are not only inappropriate, they are dangerous’.

Some, however, are not willing to restrict their anger at judicial decisions to words. Following the publication of a leaked draft suggesting the Supreme Court was indeed going to overturn Roe v Wade, Justice Brett Kavanaugh was the target of an alleged assassination attempt by an armed man arrested outside the judge’s house who was said to be ‘upset’ by the anticipated decision. As the earlier attack on the Capitol had shown, it can be a short step from intimidating threats to violent action.

Attitudes are contagious

Does the politically motivated erosion of democratic institutions and the rule of law in countries like the UK and the US influence the actions of autocrats around the world? Pietrzak, thinks that these attitudes are contagious and so ‘the rise of populism and weakening of the judiciary in other democratic states such as the US and the UK serve to legitimise illiberal and authoritarian policies in other states […]’.

For instance, attempts by Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro to undermine the legitimacy of individual judges and the election courts ahead of elections in October 2022 seem to come straight from the Trump playbook. As Goldstone notes: ‘The US has been regarded for many decades as the leader of the democratic world. There have been a number of autocrats who have relied on Trump to justify their autocratic behaviour.’

In Poland the government is in a long-standing battle with the EU over political assaults on the independence of the judiciary. The EU increased pressure in 2021 when it introduced the concept of a ‘conditionality regulation’ whereby funding may be withheld from a state due to rule of law backsliding. The EU subsequently made the release of €35bn in Covid-19 recovery funds contingent on the Polish government abolishing a judicial disciplinary body which it has used to attack judges for political reasons, and on reinstating judges suspended for political motives. The Polish government considered that it had done enough after proposing legislation to replace the disciplinary body. National legal and human rights non-governmental organisations, in addition to the Polish Judges Association, describe the suggested changes as ‘cosmetic’. The EU too is dissatisfied and is withholding the money until the Polish government does more.

The chair of Poland’s governing PiS party and de facto national leader, Jarosław Kaczynski, went on the attack by threatening to veto future EU initiatives and unseat EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen. Kaczynski declared that if the EU Commission ‘tries to push us against the wall, we will have no choice but to pull out all the weapons in our arsenal’. Pietrzak thinks that the EU should stand firm and take a long-term view: ‘It seems to me that Poles need a healthy democracy and the rule of law over the upcoming decades, more than they need the recovery funds’.

Such an aggressive stance by Kaczynski – even though Poland is the recipient of the largest share of EU funding – is assuredly emboldened by other democratic governments challenging rule of law norms at both the national and international levels in the name of ‘the people’. As Pietrzak observed: ‘Populism spreads like wildfire’. He stresses that in such circumstances lawyers have a key role to play: ‘We as lawyers are uniquely equipped to act as firefighters. I am proud to say that Polish lawyers and judges have spent the last seven years desperately trying to put out this fire – even in the face of repression from the political authorities.’

International law suffers when it is treated with contempt by governments, as Fowles notes: ‘International law is only as strong as the political commitment of the most powerful nations. Both the UK and (under Trump) the US appear to have abandoned adherence to key parts of the international legal system.’

How to stop the rot

Because statements by politicians are uniquely influential and often widely disseminated, Fowles thinks it is time for a ‘truth’ law arguing that ‘truth-telling is as important to a democratic constitution as principles like the rule of law or parliamentary sovereignty. As such it requires equivalent protection’. He suggests that the words of politicians should be judged according to clear legal criteria: ‘(a) Was this statement, on the balance of probabilities, true or false? and, if false (b) did the person who made the statement know, or should they have known, that it was false?’ He contends that courts are entirely capable of determining such questions without political bias and that we already trust them to do so ‘in every case from road traffic accidents to multi-million-pound investment disputes’.

Truth-telling is as important to a democratic constitution as principles like the rule of law or parliamentary sovereignty. As such it requires equivalent protection

Dr Sam Fowles

UK Barrister and Constitutional Law Expert

Goldstone, however, worries that passing a truth law to protect judges from political attack will only undermine other parts of the democratic system and that by this stage we would already have lost the battle: ‘It would seriously impact on freedom of speech – a bedrock requirement for the rule of law. If there is no public support for independent judges, the criminal law cannot effectively provide it.’

Fowles accepts that getting politicians to be more honest is only one part of the solution and that there is no ‘silver bullet’ that can deal with all current threats to the rule of law. In his view part of the problem lies in powerful vested interests in two areas, namely ownership of the media and funding of political parties. Fowles suggests the solution is to ‘break up news organisations that obtain outsize dominance of the news-consuming audience’ and that ‘capping donations […] will curtail the influence of those able to fund an entire election campaign out of their own pocket’.

Goldstone agrees that the media is key: ‘The media in democracies is a crucial protector of democracy and the rule of law. Public leaders, both political and those in civil society, should be encouraged to speak out in protection of the independence of judges […] education plays a critical role in protecting the rule of law.’

There seems to be a consensus that, in addition to the dissemination of unbiased information by the media, public understanding of how democracies should work is weak and an improved education at all levels is thus needed. Pietrzak thinks that countering the idea that the judiciary is an impediment to democratic rule requires ‘civic education and long-term cultivation of a strong civil society’. He acknowledges that more should have been done earlier: ‘This is perhaps where Polish legal communities [have] failed to be sufficiently active over the three decades since the fall of communism. Judges and other legal professionals are now very engaged in building civic awareness and respect for constitutional values.’

In the UK, legal bodies have appreciated that their role is central. The Law Society, for example, has suggested to the UK government that it works jointly with the legal profession to improve public understanding of the constitution: ‘We would welcome an enhanced commitment to public education about how our constitution works, including why the independence of the legal system is so important’, says Denyer. ‘We suggested the government could introduce something of this nature […] They have yet to take us up on this suggestion […] but it isn’t too late.’

Stepping back centuries

The growing political resistance to the rule of law echoes the 17th century contest between the influential political philosophies of Thomas Hobbes and John Locke. While Hobbes championed the rule of one strong person who held absolute civil, military and judicial power, Locke believed that good and fair government required the separation of powers and legal limits upon the authority of the executive. To Locke, the law was superior to the executive and thus ‘where there is no law there is no freedom’.

Politicians assaulting the rule of law in the 21st century, seem willing, if not eager, to wind the clock back from modern democracy to earlier eras. Some actions, in established as well as transitioning democracies, might seem to echo a time still within living memory in Germany when Adolf Hitler declared: ‘I expect the German legal profession to understand that the nation is not here for them but they are here for the nation [...] From now on, I shall intervene in these cases and remove from office those judges who evidently do not understand the demand of the hour.’

Is this view too alarmist? Maybe, but we ignore the warning signs at our peril. As Thatcher reminds us: ‘The first duty of government is to uphold the law. If it tries to bob and weave and duck around that duty when its inconvenient, if government does that, then so will the governed, and then nothing is safe – not home, not liberty, not life itself.’

Anne McMillan is a freelance journalist and writer. She can be contacted at mcmillan.anne@orange.fr

Image credit: jojje11/AdobeStock.com