Reckoning, reconciliation and respect

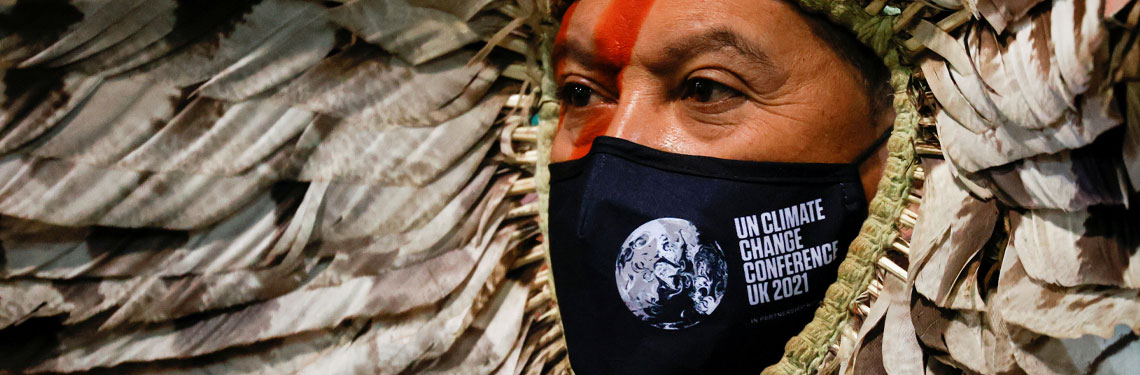

Indigenous Amazon delegate Romancil Gentil Kreta attends the COP26 conference in Glasgow, Scotland, 3 November 2021. REUTERS/Phil Noble

The pandemic exacerbated pre-existing inequalities facing Indigenous peoples worldwide, but COP26 brought them centre stage. Global Insight looks at the pressing need to make Indigenous voices part of the solution.

The true impact of the pandemic on Indigenous peoples is still to be determined, but inadequate state responses, misinformation and inequitable access to vaccines have undoubtedly subjected them to higher risks of infection and death from Covid-19 than any other ethnic group. Even before the pandemic, many groups faced erosion, flooding, desertification, land degradation and other extreme weather patterns that threatened to wipe out entire communities. For small island nations – where the risk of being completely swallowed whole by rising sea levels grows daily – the impending threat of the climate crisis is very real.

It was in this context that Indigenous communities stepped up to play a pivotal role at the COP26 climate talks in 2021. Twenty-eight Indigenous representatives engaged directly in the discussions with hundreds of other people representing their groups informally. It closed on a positive note with the adoption of the Glasgow Pact, which highlighted ‘the important role of civil society, including youth and indigenous peoples, in addressing and responding to climate change, and highlighting the urgent need for action’.

Rodion Sulyandziga, member of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change’s (UNFCC) Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples Platform Facilitative Working Group, said: ‘This is a strong achievement and historic progress under the UNFCCC, to bring the indigenous knowledge holders to the table to voice solutions and humanise the impacts of climate change.’

Indigenous peoples take centre stage

The prominence of Indigenous voices at the talks suggests there is a growing awareness of the importance of addressing the challenges facing Indigenous communities worldwide. Indigenous groups have some of the highest incarceration rates in the world. In Australia and Canada alone, they make up around a third of prison populations.

Many Indigenous communities still suffer from the adverse effects of historical government policies. In Canada, between 1894 and 1947 an estimated 150,000 Indigenous children were separated from their families and forced to attend 130 Indian residential boarding schools run by religious authorities and financed by the federal government.

Aboriginal men watch Prime Minister Kevin Rudd apologise to Aboriginal Australians for their historic mistreatment on a big screen outside Parliament House in Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia, 13 February 2008. REUTERS/Mick Tsikas

The last residential school closed its doors in 1996, but around 6,000 children are thought to have died while attending the schools and many reports of physical, sexual and verbal abuse and unsanitary living conditions have since surfaced.

The system has been widely denounced for its deliberate efforts to eradicate Indigenous children’s culture, language and identity. In 2007, a class action settlement agreement was reached between the federal government, legal counsel for former students, legal counsel for the churches and the Assembly of First Nations.

David Paterson, Chair of the IBA Indigenous Peoples Committee, was part of the legal team that brought the class action and was on the Oversight Committee for the residential school compensation process. He helped broker the settlement agreement that offered CAD 1.9bn in compensation to around 86,000 former residential students for the abuses they suffered in the school system. A Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was established as part of the agreement and made 94 calls to action directed at all levels of government and society to ‘redress the legacy of residential schools and advance the process of Canadian reconciliation’.

In 2008 the federal government finally issued a formal apology. In 2015, a landmark TRC report described the system as ‘cultural genocide’. Paterson says the system has undoubtedly contributed to the erosion of social and economic rights of Indigenous communities across Canada. However, he says the work of the ongoing TRC gives some grounds for optimism. ‘This has energised a great deal of discussion and activity throughout society as provinces revise their education curricula, law societies make training in Indigenous societies mandatory, and other groups take up relevant calls to action’, he says.

Some basic steps – such as creating an independent body to assess the progress of reconciliation in the country – have yet to be taken. ‘But six years after the TRC issued its calls, they are still regularly in the news and the subject of commentary and discussion and represent a standard of conduct to which the government and other organisations are called to adhere’, says Paterson. ‘It is too early to measure the long-term impact of all of this, but it stands in sharp contrast to the report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, tabled in 1995, which included hundreds of recommendations – none of which were implemented.’

A grave reminder

The impact of the abuse is still strongly felt in many communities and came back to haunt the federal government in 2021 as several unmarked graves containing the remains of more than 6,500 Indigenous children were discovered at former residential school sites across the country.

‘While Indigenous communities are strong and resilient, survivors and their descendants share in the effects of intergenerational trauma and the loss of language, culture, and teachings’, says Kevin O’Callaghan, head of Indigenous Law at Fasken Martineau Du Moulin in Vancouver and a member of the IBA Business Human Rights Committee Advisory Board. ‘Even if, at law, Indigenous rights are fully realised, the effects of denying their rights and dignity for so long will reverberate for generations.’

The discoveries sparked national and international outcry. They also heightened concerns that the government had simply replaced one discriminatory child welfare system with another, says Kelly Harvey Russ, an Indigenous lawyer and family and child protection specialist in Vancouver. ‘I accept that some people say that the residential schools were a way to sever the transmission of Indigenous culture from one generation to the next – that clearly was their intent’, says Russ. ‘When the residential schools came to a close, you started to see an uptick in the number of Indigenous children in care provincially. Basically, you are switching one institution for another to take Indigenous children from their communities and stop the transmission of culture.’

Russ, himself a victim of the so-called ‘Sixties Scoop’, which saw Indigenous children separated from their families and placed in foster homes, says the number of Indigenous children in care in Canada is still shockingly high. He was born in Haida Gwaii, an archipelago just off the coast of British Columbia (BC), but was removed from his family and spent 13 years in the foster care system more than 200 kilometres away in Prince Rupert. He went on to qualify as a lawyer and has focused on child protection issues for much of his career.

In November 2021, Russ was one of five Indigenous lawyers elected to the leadership of the Law Society of British Columbia after a hotly contested election process. Each lawyer ran separately, but their combined election marked the largest number of Indigenous lawyers ever to sit on the board and was hailed as a step change for the diversity of the province’s legal profession.

Children’s shoes and toys are placed at a memorial in front of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School after the remains of 215 children were found in Kamloops, British Columbia, Canada, 31 May 2021. REUTERS/Dennis Owen

‘The election of five Indigenous lawyers is unprecedented and a significant milestone in the Law Society’s ongoing effort to increase the involvement of Indigenous peoples in our governance’, a Law Society spokesperson told Global Insight. ‘In our Truth and Reconciliation Action Plan, we set a goal of recruiting Indigenous candidates and the election result is an encouraging sign we are making progress.’

It was also a welcome development after the Law Society was criticised earlier in 2021 for its handling of a discipline case against a lawyer accused of significant abuse of Indigenous clients in the residential school compensation process. The lawyer, who admitted professional misconduct in relation to 17 clients’ cases, was handed a one-month suspension and fined CAD 4,000, but many felt his punishment was too lenient.

Commenting on the case, a Law Society spokesperson said: ‘No one is happy with the outcome. It revealed the frailties of the adversarial system and raises questions about the ability of our current regulatory process to engage, address and accommodate complainants and witnesses, particularly Indigenous persons, who may be experiencing vulnerability or marginalization.’

The case prompted the Law Society’s board to establish an Indigenous Engagement in Regulatory Matters Task Force in July 2021 to review its regulatory processes. It is also taking further steps to assess the ‘unique needs of Indigenous people’ in its 2021–2025 Strategic Plan.

Russ believes the strong Indigenous presence on the board bodes well for the wider BC legal profession. ‘Electing the five of us in the most recent election actually tells me that they're very receptive and they're very open to accepting Indigenous peoples within the legal profession and moving forward with reconciliation within the Law Society and overall within Canadian society’, he says.

Today, a successful child protection lawyer and married – to a Supreme Court judge no less – with two children of his own, Russ is keenly aware that many others with his background won’t have been nearly as lucky. ‘I'm incredibly proud to be Canadian, but I'm also ashamed about some of the things that we've done towards Indigenous people’, he says. ‘I didn't have a tragic outcome. I'm sitting here talking to you as a lawyer, as a bencher of the Law Society, but then I also think the cost of that is the loss of connection to my own community. I still have family members there and it's difficult to maintain relationships when you haven't grown up in that community.’

In 2016, the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal found that the federal government had unfairly allocated fewer funds for child and family services for Indigenous communities compared with non-Indigenous families, duly forcing more Indigenous children into foster care. It ruled that there should be compensation for each First Nations child unnecessarily placed in foster care.

Russ says the recent discoveries of yet more mass graves have been a stark reminder that Canada’s child protection system needs urgent reform. ‘It’s really forced us as a Canadian society to focus on correcting what we are doing now on the ground when it comes to child protection’, he says. ‘It’s going to take time, but every day that goes by is another day an indigenous child is in care that doesn't deserve to be there.’

In December 2021, the federal government announced it was earmarking CAD 40bn ($31.2bn) to settle several outstanding Indigenous child welfare lawsuits and compensate Indigenous children and families in foster care. The agreement – the largest class-action settlement in Canadian history – was confirmed in January and the funds are due to be split between compensating victims and reforming the country’s child welfare system.

Welfare disparity

The welfare of Indigenous children has also come under the spotlight once again in Australia where Aboriginal children make up at least 99 per cent of juvenile detainees. Despite findings by a Royal Commission in 2017 that identified systemic failures in the Northern Territory’s (NT) detention centres, in December the state’s Acting Children’s Commissioner, Sally Sievers, raised her concerns that rising prisoner numbers and staff shortages had resulted in overcrowding and ‘unacceptable’ living conditions at the Don Dale and Alice Springs detention centres.

Although the NT government accepted all the Royal Commission’s 227 recommendations in full or in principle, reform to date has been ‘piecemeal’, according to David Woodroffe, principal legal officer at the North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency (NAAJA). The Royal Commission also recommended the closure of Don Dale and raising the age of criminal responsibility to at least 12.

However, Don Dale has since expanded its capacity to hold 120 more beds and Woodroffe says the number of youths in the system is ‘consistently high to overcapacity’. In 2021, a court ordered the state to pay out A$35m to a group of young people mistreated in Don Dale between August 2006 and November 2017.

Recent changes have only exacerbated existing problems in the system. ‘May 2021 saw the restrictive new bail legislation for breaches of serious bail offence, that can include breaches of bail curfew or electronic’, says Woodroffe. ‘We are seeing children as young as 10, 11, 12 on remand in detention. Aboriginal children in Alice Springs are arrested for breaching their bail for either being at another family residence, failure to charge their electronic device due to family poverty or is unsafe to stay at that location.’

He says broader reforms and are still sorely needed and funding should be redirected towards community programmes to provide greater support for children and their families: ‘The Australian and Northern Territory governments have committed to “Closing the Gap” on Aboriginal youth incarceration by reducing it by 30 per cent by 2031. However, this cannot occur within the same existing institutions and infrastructure, it requires a paradigm shift of empowering Indigenous communities and peoples with the autonomy for the care, safety and supervision of their children through community-based systems and organisations.

I would say Indigenous peoples across the world have not just been left behind, but they've been pushed further behind

Katherine Meighan

General Counsel, UN International Fund for Agricultural Development

In April 2021, NAAJA was one of 18 charities selected to receive funding from the IBA’s Frontline Legal Aid Fund. Through the IBA donation, the charity has undertaken a project to provide training and skills in mediation and peace-making with Elders and community leaders from remote Aboriginal communities.

Woodroffe says the funding couldn’t have come at a better time for such communities, which have suffered from a lack of embedded services, infrastructure and quarantine isolation and a spike in domestic and family violence throughout the pandemic.

The funding has already enabled NAAJA to conduct training workshops with four remote communities and there are plans to run an intensive workshop in Katherine in 2022. Woodroffe says it has also helped NAAJA continue its focus ‘on building the capacity and empowering Aboriginal communities with local based community groups with mediation, community safety, and alternative pathways from the criminal justice system’.

Pandemic pressure

The pandemic has undoubtedly put more pressure on Indigenous communities worldwide, says Katherine Meighan, Associate Vice-President and General Counsel at the UN International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). ‘When you look back at the last six years of the Sustainable Development Goals, I would say Indigenous peoples across the world have not just been left behind, but they've been pushed further behind’, she says.

‘It is a crisis within a crisis because things were already critical and then Covid just exacerbated it’, says Meighan. ‘This is demonstrated by the continuous grabbing of Indigenous peoples’ lands and resources; the criminalisation of Indigenous peoples; their increasing poverty and hunger; loss of livelihoods and cultural heritage. We are also seeing increased violence against Indigenous women and girls, and rising inequality. Covid-19 is just exacerbating these kinds of structural inequities, as well as what I would call pervasive discrimination against Indigenous peoples.’

O’Callaghan says the pandemic has disproportionately affected access to justice in many Indigenous communities and many feel more estranged from the justice system than ever before. ‘Practically speaking, many Indigenous communities are remote and rural and already experience challenges accessing legal resources and services’, he says. ‘As administrators of these resources and services turned to the internet to fill the gaps in the system, members of Indigenous communities faced the barrier of having limited-to-no access to the internet: only a third of on-reserve households have access that meets target internet speeds. This is compounded with the fact that Indigenous communities already experience disproportionate public health barriers, such as food insecurity, overcrowding, and lack of access to clean drinking water and medical services.’

Indigenous Hupdah people living at the Brazil-Colombia border in small communities in the Amazon rainforest, Amazonas, Brazil, 3 March 2021. Shutterstock.com/BW Press

However, Meighan says many Indigenous communities have shown impressive signs of resilience throughout the pandemic (see box: Indigenous initiative). However, in the face of increasing economic and social marginalisation she recognises that many groups are also at increased risk of human rights violations. ‘We're also seeing, unfortunately on the discrimination front that Indigenous peoples are facing the targeting of their leaders and activists’, she says. ‘Some of this is under the cover of the scaling-up of emergency measures, depending on the country. But because of their generally more isolated stance, the lack of access to communication and information increases the risk of human rights violations.’

There’s also an ever-increasing risk that such violations will go unreported. ‘We have a major lack of disaggregated data relative to Indigenous peoples’ experiences with Covid-19 and the absence of adequate social services is another issue’, she says. ‘It's hard to say precisely what these figures are, but from ad hoc and anecdotal evidence, this is something that we've been hearing and it’s very concerning to us.’

Respecting land, culture and climate rights

In August 2021, José Francisco Cali Tzay, the UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, criticised the way that global powers had treated Indigenous communities throughout the pandemic. ‘Economic recovery measures have prioritised and supported the expansion of business operations at the expense of indigenous peoples, their lands and the environment’, he said in a statement. ‘Worldwide, the Covid-19 pandemic has been a catalyst for States to promote mega-projects without adequate consultation with indigenous peoples.’

This has been particularly evident in Australia, where in May 2020 mining corporation Rio Tinto was granted government approval to blast 46,000-year-old sacred rock shelters in Juukan Gorge in the Pilbara, Western Australia (WA), despite strong objections from traditional owners over the site's cultural significance. An independent inquiry into the incident called for a new national cultural heritage protection framework. In December, the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination cited concerns that a controversial new cultural heritage bill being mooted in WA was entrenched in ‘structural racism’. Later that month lawmakers in WA passed the bill, which replaces the Aboriginal Heritage Act 1972, including the controversial Section 18 approvals process, which allowed the destruction of Juukan to take place. Critics argue the new law risks putting the interests of companies above traditional landowners and ultimately gives the WA government the right to approve projects in the event of a dispute between landowners and mining companies.

The inquiry laid bare the system of inequality that enables the mining industry and the rest of Australia to prosper, at the expense of Aboriginal heritage

Professor Deanna Kemp

Director, Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining, University of Queensland

Professor Deanna Kemp is Director of the Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining at the University of Queensland in Brisbane. Although the new legislation is disappointing, she believes much has been learned from what happened at Juukan. ‘The inquiry laid bare the system of inequality that enables the mining industry and the rest of Australia to prosper, at the expense of Aboriginal heritage’, she says.

‘We also gained access to deep detail about the events leading up to the blast, and the underlying system that enabled the “legal act” of destruction’, she says. ‘Few of us were aware of the full effect of the gag clauses and Section 18s, and how they worked in practice. We also learned how markets reward production, how corporate leaders let us down, and the effort it takes to get companies to reveal anything much – even when they cause harm. If we had relied on Rio Tinto’s so called “independent” Board Review, we would know very little at all.’

Indigenous initiative

Despite the ongoing challenges posed by Covid-19 variants, Indigenous communities are continuing to forge new initiatives to recover from the pandemic, José Francisco Cali Tzay, the UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, told the UN Human Rights Council in September 2021.

He said that instead of relying on state aid, many Indigenous groups were using traditional know-how to mitigate the adverse impact of the pandemic on their communities. In particular, he pointed to examples of groups using their scientific knowledge of plants, roots and medical practices to boost their immune systems and using traditional seeds and crops to strengthen food sovereignty. However, Cali Tzay said the pandemic had also revealed just how important it was for Indigenous land rights to be respected. ‘The protection of indigenous territories was central, as it not only helped indigenous peoples to recover from the health crisis, but also as it promoted food security and sustainable livelihoods, increasing resilience in the face of future pandemics’, he said.

Katherine Meighan, Associate Vice-President and General Counsel at the UN International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), agrees that Indigenous communities have displayed considerable resilience over this period.

She cites the example of Guatemalan women’s cooperative Mujeres Cuatro Pinos, which, with IFAD’s financial support, became the first women's cooperative in Guatemala to begin exporting goods to the international markets. Today it employs around 450 women – including 130 young women – and has the capacity to produce nearly 150,000 kilograms of vegetables each month.

‘They run their own training and knowledge management centre to promote regional exchange of knowledge and best practice’, says Meighan. ‘It shows the importance of traditional agricultural practices and the benefits of learning from Indigenous people as stewards of the land and then taking that and helping them to scale it up. But it’s vital to keep Indigenous peoples in the centre so they decide what projects they need, how to implement them, what to achieve and how to use their lands and territories.’

Chronic malnutrition affects half of all children under the age of five and 62 per cent of Indigenous children. In Guatemala, where 80 per cent of Indigenous groups live in poverty, IFAD has been working closely with local communities to maximise the potential of heirloom seeds. ‘During the civil war in Guatemala, many indigenous seeds were almost lost because of the conflict’, says Meighan. ‘What was found in Guatemala is that heirloom or indigenous seeds have nutritional properties that help prevent malnutrition in children and can also be more drought resistant and resistant to climate shocks.’

IFAD has been supporting other countries worldwide to set up similar heirloom seed banks and Meighan says they could be a game-changer for Indigenous communities in challenging times. ‘They can help solve chronic malnutrition and food shortages and are also preserving cultural heritage’, she says.

A spokesperson for Rio Tinto said the company was ‘absolutely committed to ensuring the events at Juukan Gorge are never repeated’ and that it supported efforts to strengthen mechanisms to protect Aboriginal cultural heritage. The spokesperson said: ‘We have spent the past 18 months making major changes right across our business to better protect Aboriginal heritage. This includes reviewing our mine plans, improving agreements, and strengthening and rebuilding relationships with traditional owners. We are also shifting to a model of co-management of country with traditional owners to deliver better outcomes on the ground for Aboriginal people. This work is ongoing.’

The mining corporation said it would also be ‘re-consulting’ in relation to any granted Section 18 approvals and would only pursue Section 18 applications where it had ‘a letter of non-objection’ from traditional owners.

Although some consider the latest WA legislation a huge setback for Aboriginal rights in Australia, Kemp says momentum in other areas is encouraging. ‘There are investor initiatives, such as the Dhawura Ngilan Business and Investor Initiative, and initiatives to improve federal law such as the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 to strengthen the ability of Indigenous Peoples to have their sites protected against state interests.’

It’s really the first time we’re seeing a global partnership of influential nations and donors responding so dramatically to the evidence of indigenous people, playing an outsized and unsung role in conserving the nature of the world

Victoria Tauli Corpuz

Former UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples

Progress globally is also promising. At COP26, world powers gave one of the strongest indications yet that Indigenous communities were entitled to receive greater financial support in the fight against the climate crisis. In partnership with 17 funders, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, the UK and the US pledged to invest $1.7bn from 2021 to 2025 to support Indigenous peoples and local communities’ forest stewardship.

Victoria Tauli Corpuz, an indigenous activist from the Philippines and the former UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, said in a statement that she welcomed the financial pledge. ‘It’s really the first time we’re seeing a global partnership of influential nations and donors responding so dramatically to the evidence of indigenous people, playing an outsized and unsung role in conserving the nature of the world.’

Meighan, who participated virtually in a side event with Tauli Corpuz, says the pledge recognises the real-time impact of the climate crisis on Indigenous communities and that they are central to finding workable solutions. ‘We have hope from COP26 in that Indigenous peoples were there and were heard as they have never been before and they were recognised within the COP26 final decision’, she says. ‘But we still have an enormous road ahead in terms of supporting Indigenous peoples. Their voices are starting to be heard at a more global level, but at the next COP in Egypt, I'd like to see that really amplified.’

Ruth Green is the IBA Multimedia Journalist and can be contacted at ruth.green@int-bar.org