Expanding BRICS bloc poised to challenge the international order

Stephen Mulrenan, IBA Asia CorrespondentMonday 6 November 2023

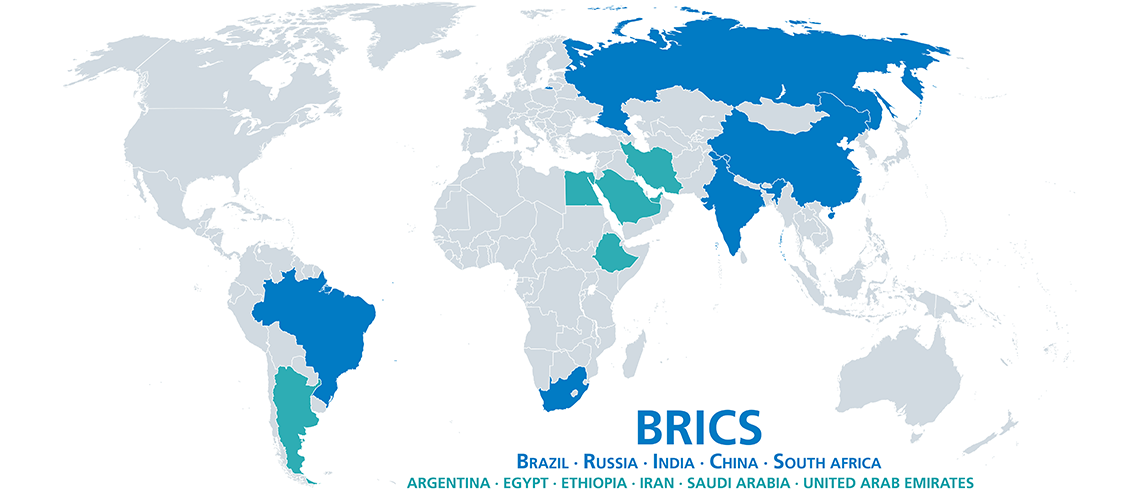

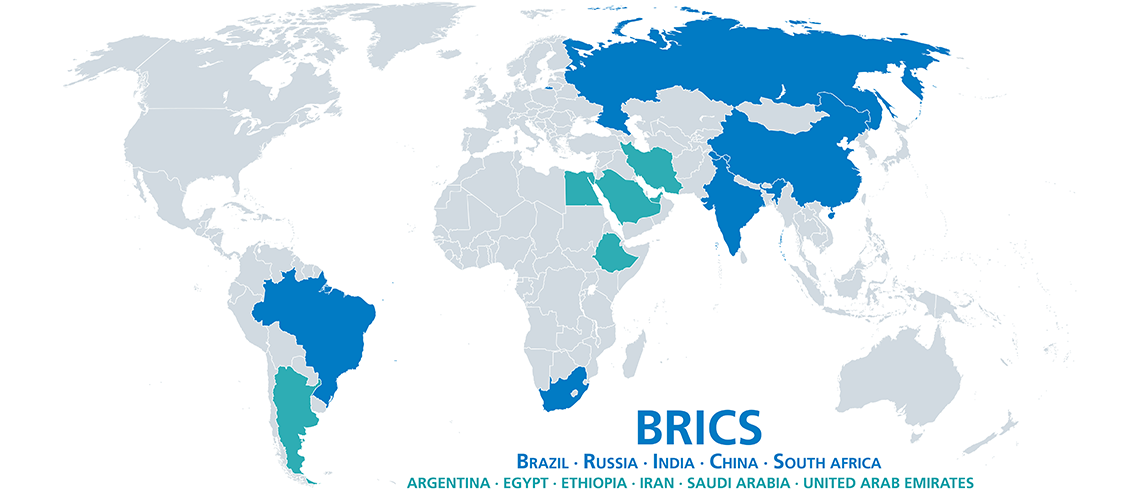

Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates are set to join the BRICS geopolitical bloc from the start of 2024, the largest such expansion and the first in 13 years. Previously, the bloc consisted of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. Despite the group’s growth, more than 40 other developing nations who have requested to join must wait.

The decision was made at the 15th BRICS Summit in Johannesburg in August, where the other major issue on the agenda was reducing dependence on the US dollar. ‘While progress on the latter was modest in the final declaration, the expansion was surprising’, says Carol Monteiro de Carvalho, Co-Chair of the IBA International Trade and Customs Law Committee and a partner at Monteiro & Weiss Trade in Rio de Janeiro.

Many countries also used the occasion to voice their growing disenchantment with the prevailing, Western-led international system, exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic, when life-saving vaccines were hoarded by developed nations. ‘BRICS has become an attractive magnet for countries that don’t fit within the structures of the US-dominated international order, including Iran and Venezuela, which face economic sanctions, and Argentina, struggling to access the financial system to address its structural economic crisis’, explains Monteiro de Carvalho.

BRICS – formed of countries with significant growth potential – began convening during the global financial crisis of 2008 before being founded as an informal club in 2009 at the behest of Russia. South Africa became the first beneficiary of the bloc’s expansion in 2010.

BRICS has become an attractive magnet for countries that don’t fit within the structures of the US-dominated international order

Carol Monteiro de Carvalho

Co-Chair, IBA International Trade and Customs Law Committee

While BRICS’ agenda initially focused on reforming multilateral financial institutions, particularly the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank, this gradually gave way to a geopolitical focus, due in part to US efforts to contain China’s technological expansion as well as Russia’s annexation of Crimea and invasion of Ukraine.

Since 2009, BRICS countries have launched initiatives that challenge the US-led financial system and international order. These include the creation of the New Development Bank (NDB), as an alternative to the World Bank and the IMF, and the launch of the BRICS Payment System (BPS), designed to reduce the reliance of BRICS countries on SWIFT, which is dominated by the US. ‘The expansion of BRICS and its initiatives have the potential to significantly impact the global financial system and international order’, says Ramesh Vaidyanathan, Co-Chair of the IBA Asia Pacific Regional Forum and a partner at Advaya Legal in Mumbai. ‘For example, the NDB […] and BPS could help to reduce developing countries’ reliance on Western financial institutions and the US dollar.’

Some analysts argue that the expansion of the BRICS represents a firm rejection of the G7 and the liberal international order (LIO) as it challenges their dominance and legitimacy in global governance. BRICS countries have often accused the G7 and the LIO of being exclusive and unrepresentative of the diverse interests and needs of the developing world. By inviting more countries to join the bloc, BRICS aims to create an alternative, based on what it states are principles of sovereignty, non-interference and mutual benefit.

Other commentators say the bloc’s expansion simply reflects a desire to adapt the G7 and the LIO to the changing realities of the 21st century. ‘BRICS countries have not completely abandoned or opposed the existing international institutions and norms that were established by the G7 and the LIO, but rather have sought to participate in and influence them more actively and effectively’, says Vaidyanathan. ‘For example, BRICS countries have contributed to the IMF and the World Bank.’

Even before the addition of new members, BRICS countries accounted for 40 per cent of the world’s population and a quarter of global gross domestic product. However, the bloc’s ability to seize its geopolitical moment may depend on its ability to overcome long-standing internal divisions.

The economies of BRICS countries are vastly different in scale, while the governments of its members often have divergent foreign policy goals. For example, China, Iran and Russia view the bloc as a counterweight to the West, while Brazil and India continue to nurture close ties with the US and Europe. This not only complicates the bloc’s consensus decision-making model but also led White House National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan to conclude in August that BRICS won’t evolve into a geopolitical rival of the US as it’s ‘a very diverse collection of countries in its current iteration — with Brazil, India, South Africa’s democracies; Russia and China as autocracies — with differences of view on critical issues in the Indo-Pacific, in the war in Ukraine’.

This argument tends to focus on several perceived adverse consequences, for example that BRICS will be less effective in achieving its goals if its members can’t reach consensus on key issues, while it’s possible that major powers, such as the US and China, could exploit divisions within BRICS to advance their own interests.

An alternative school of thought is that any internal divisions could reflect the bloc’s diversity and thus be a source of strength, says Vaidyanathan. ‘This is because BRICS countries can cooperate on areas of mutual benefit, such as trade, investment [and] infrastructure’, he says. ‘But they also […] do not impose any ideological or political conditions on their partnership.’

A third view is that the impact of internal divisions on BRICS’ global role depends on various factors and circumstances that may change over time. These include the motivations, interests, actions and reactions of each BRICS member and partner, and the responses of others in the international system. It also depends on the nature and scope of the global issues that require collective action and the evolution of the international order itself.

Vaidyanathan says the impact of internal divisions among BRICS countries is dynamic and contingent and, as such, both opportunities and challenges for cooperation or competition with other actors on different issues and regions could be created. ‘Internal divisions could hinder BRICS’ ability to act as a unified front on global issues such as climate change or trade reform’, he says. ‘But they could also promote BRICS’ global role by making the bloc more adaptable and resilient to change.’ Where cooperation with others takes place, this could expand the bloc’s influence, believes Vaidyanathan.

For now, the potential impact of any internal divisions remains uncertain. What’s clearer is that each BRICS country will be pleased with 2023’s summit: Brazil’s push for a common currency is being taken seriously; Russia was represented despite its leader facing charges of alleged war crimes in Ukraine; India managed to retain its commitment to strategic autonomy; China was able to grow BRICS’ membership; and South Africa hosted a successful meeting with no public fallouts.

Image credit: Peter Hermes Furian/AdobeStock.com