Femicide, murder and other crimes against women – a social crisis

The IBA Human Rights Institute’s (IBAHRI) showcase session at the IBA Annual Conference brought the issue of gender-based killings into focus and called on the legal profession to help end this social crisis.

Helena Kennedy, IBAHRI Director: In 2022, UN Women recorded the highest yearly numbers of intentional killings of women and girls in the past two decades. And they recorded nearly 89,000 women reportedly killed. Let me tell you, when it comes to statistics, never rely on them. Because in this area, very often the data is not clearly indicating how the killing has taken place or that they may have happened at the hands of people with whom the women have been in relationships, or members of their own family – or indeed what's called honour killings. And that many of those killings are never recorded as being violence specifically against women and the gendered nature of the crime is often not fully recorded.

As advocates and guardians of justice, lawyers, judges and members of the legal community must become agents of change. You must recognise your critical role in addressing this crisis. You must push for reforms in addressing this to hold perpetrators accountable and provide support for survivors. Legal frameworks need to be strengthened.

The fight against femicide is not just about reforming the legal system. It's also about changing societal attitudes. It is also about us and the role that we play as mothers. We must engage community in discussions about the roots of gender-based violence. Education plays a vital role in this transformation initiative that promotes respect, equality and the empowerment of women as essential in changing cultural norms. Moreover, today I call upon each of you to become agents of change in this fight against femicide.

Hina Jilani, Advocate, Pakistan Supreme Court: How do we change cultures? I think it is a mistake to think that femicide, murder or crimes against women are in any way rooted in any culture or any society that claims to be civilised. I think this whole question of culture is really a cover up of a criminal mindset, an extreme form of misogyny that we justify by using either culture or religion or any other kind of justification.

We know that this violence is long and historic, that it's rooted in patriarchy and the idea that women and children were the property of the heads of the household and of men. And women as property, as being lesser, as being subordinate, has been one of the notions that has blighted our world for a very long time.

It really seemed very important to us since we were coming to Mexico, that given that the high incidence of the murder, the homicides of women and the naming of this as femicide has become commonplace here in Mexico, that we took this opportunity not just to speak about this as a problem that happens here in this nation, but that it is a global problem of great magnitude.

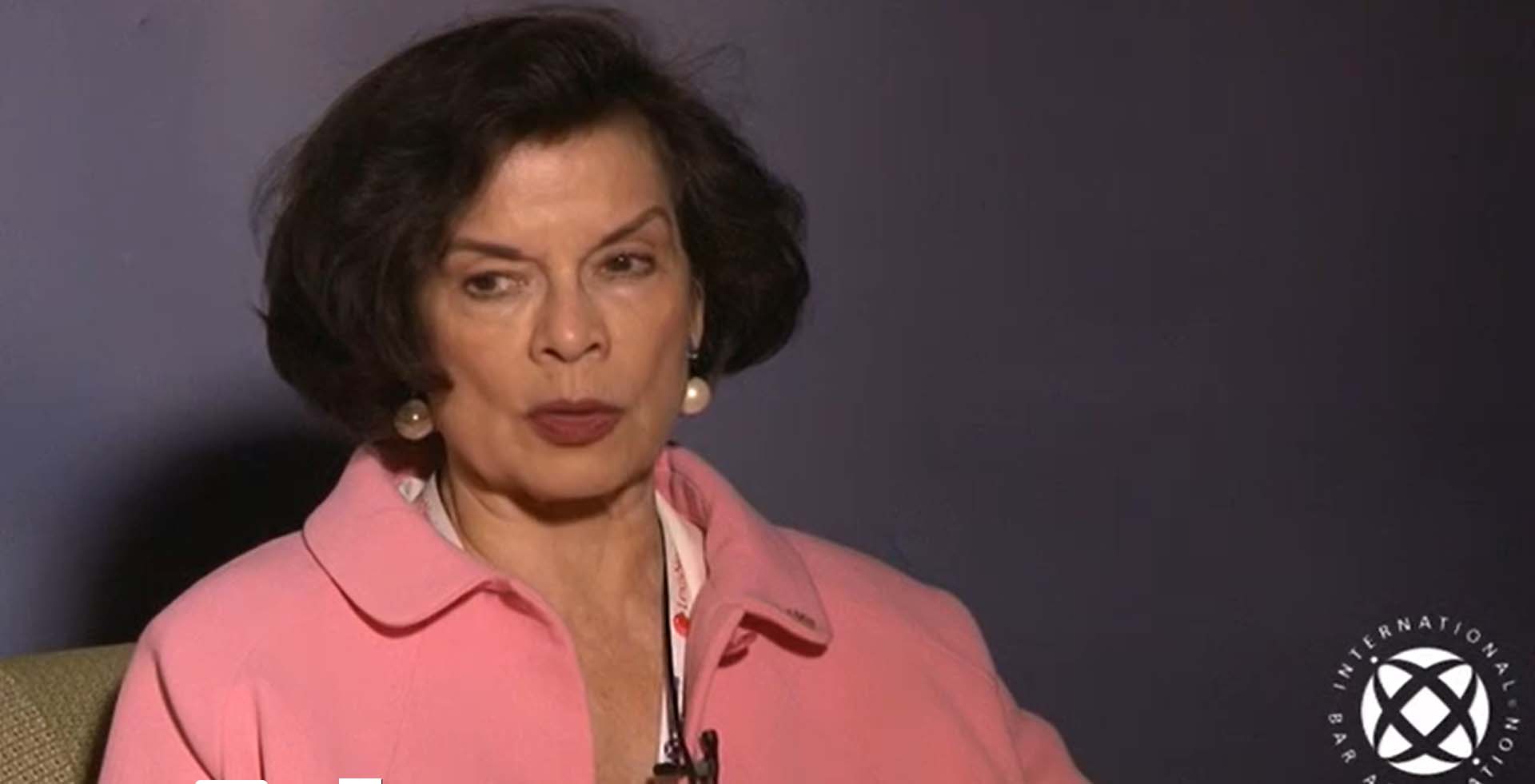

Bianca Jagger, Founder of the Bianca Jagger Human Rights Foundation: [I am] filled with both a profound sense of urgency, a great deal of concern, and also, I will say, of indignation every time I have to prepare a speech about the crimes against women. And I have to see what is happening in the world, even today in the 21st century. I can only feel indignation when I see how governments have failed women throughout the world.

Gender-based violence and in particular femicide, or feminicide, is one of the most brutal manifestations of systemic oppression against woman. It is a violation of women's fundamental human right – their right to life – which transcends borders, cultures and socioeconomic classes. According to the latest report from UN Women and the UN Office on Drugs and Crime, in 2022 alone approximately 48,000 women and girls were murdered globally by intimate partners or family members. Of course, as Helena well said, we have to question statistics, because, of course, there are so many of these women who have been murdered that we don't know anything about. The figure represents an average of more than 133 women killed every day. Each one a daughter, a sister, a mother, a friend. These statistics are not just numbers, they are a reflection of lives tragically cut short by a culture of violence and misogyny. Femicides are often driven by deeply entrenched gender stereotypes, discrimination and systemic inequalities. They are not isolated incidents. They are the culmination of a continuum on gender-based violence that disproportionately affects women.

While the world has made significant strides in addressing gender equality, we have not really achieved gender equality in any part of the world. Let's not fool ourselves. The reality remains that women, particularly those from marginalised communities, face heightened risk of violence.

Bianca Jagger, Founder of the Bianca Jagger Human Rights Foundation

[In Nicaragua], women's organisations were some of the first women that the regime of Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo began to eliminate. The government of Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo has stripped of the legal status of over 5,000 NGOs [non-governmental organisations] and foundations in Nicaragua. Human rights defenders have raised their voices, demanding greater governmental accountability. Many of these women's human rights defenders had to flee the country. Therefore, we have very few statistics to know what is happening in Nicaragua.

The situation of women and femicide is really a crisis. A significant challenge in addressing femicide in Nicaragua is the underreporting of cases which contributes to a pervasive culture of impunity. Many instances of femicide remain unreported due to societal stigma.

As advocates and guardians of justice, lawyers, judges and members of the legal community must become agents of change

Bianca Jagger

Bianca Jagger Human Rights Foundation

As advocates and guardians of justice, lawyers, judges and members of the legal community must become agents of change. You must recognise your critical role in addressing this crisis. You must push for reforms in addressing this to hold perpetrators accountable and provide support for survivors. Legal frameworks need to be strengthened.

The fight against femicide is not just about reforming the legal system. It's also about changing societal attitudes. It is also about us and the role that we play as mothers. We must engage community in discussions about the roots of gender-based violence. Education plays a vital role in this transformation initiative that promotes respect, equality and the empowerment of women as essential in changing cultural norms. Moreover, today I call upon each of you to become agents of change in this fight against femicide.

Hina Jilani, Advocate, Pakistan Supreme Court: How do we change cultures? I think it is a mistake to think that femicide, murder or crimes against women are in any way rooted in any culture or any society that claims to be civilised. I think this whole question of culture is really a cover up of a criminal mindset, an extreme form of misogyny that we justify by using either culture or religion or any other kind of justification.

In the 1980s, we were suffering in Pakistan from an extremely repressive military dictatorship that had come into existence at the end of the 1970s. [Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq] was a dictator who wanted to legitimise this illegal takeover by using religion, Islam, which is the religion of 95 per cent population in that country. The result was that their intention to control the population started with what they thought was the weakest sector, and that was women and the non-Muslim minorities. And, in the name of religion, certain laws were imposed in a bid to the so-called Islamisation of Pakistan. This distorted version of Islam was imposed, firstly, targeting women. Discriminatory laws were not just discriminatory, they were harmful to women, put their lives at risk, their liberty at risk. There was a law which was called the Zina Ordinance that was imposed. This is a law that made any kind of extra-marital relationship a crime which was punishable by stoning to death.

I used to work in prisons even before I became a lawyer. But since I had become a lawyer in the late 1970s, I worked in prisons and suddenly I saw the prison population of women increase. And the root cause were these laws of Zina mostly, which were abused or used against women to punish them for exercising any kind of autonomy with respect to any part of their life.

We realised that women's rights cannot be promoted in isolation

Hina Jilani

Advocate, Pakistan Supreme Court

Hina Jilani, Advocate, Supreme Court of Pakistan

I'm basically a human rights, a democracy rights and a rule of law activist. And I thought what was happening to women was directly opposed to any kind of democratic value or the preservation of the rule of law. Being a lawyer, I thought at that time my role would be important, as a woman and as a lawyer, to make sure that this is not just a fight in the streets, but it is also a fight that we take to the legal platforms so that the institution of justice understands how conservative-biased mindsets cannot do justice. In an environment where there is no independence of the judiciary, but also no independence of thought, this was not an easy task. And of course, we struggled initially because we thought that this was a women's issue. It wasn't. It was a much broader and larger issue for the preservation of Pakistan's society and the responsibility of what the state should be doing and should not be interfering in. After initial struggles, we realised that women's rights cannot be promoted in isolation.

This movement of women became very strong and more influential and gained more public credibility once we had linked our causes with the calls for restoration of democracy, with the calls of strengthening the rule of law in the country.

Dubravka Šimonović, former UN Special Rapporteur: I was appointed as Special Rapporteur on violence against women and girls, its causes and consequences in 2015. At that time, my first act was to call states to establish a femicide prevention watch at the national level. And when I issued a statement during that process, I had problems with the United Nations because the press office told me that femicide is not a UN term, that I could not use it.

For six years I have promoted usage of this term at the UN level. And at the beginning I had objections from states. They said this is not happening in our countries. And I said: we are speaking about gender-related killings of women, that are a form of gender-based violence against women that are happening in all states, all over the world. So, we need to define what we are speaking about.

When I started with Femicide Watch [an initiative focusing on femicide prevention], I called states to collect comparable data on femicide to establish, at the national level, interdisciplinary bodies to study femicide cases and to determine from those cases what the shortcomings at are the national level, what is not in line with accepted international standards in this area for elimination of violence against women and then to recommend measures to governments to change those laws or their implementation that are not in line with the practice. And those countries that have started to collect data now have clear data showing that in cases of intimate partner killings, more than 85 per cent of victims are women. This shows that in this case, we need to focus on prevention. And femicides are preventable in many, many cases. What we need to do is to look at social, cultural, religious and legal norms at the national level.

Now we have the Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence. I was, for two years, co-chair of the drafting committee that elaborated that convention and this convention is now providing a very clear roadmap with new standards related to SOS helplines, shelters, protection orders and risk assessments that should be done in any case of violence against women. Those are really new things that we need to have implemented in all countries, all over the world, but there is still a lack of knowledge and what we need is to transfer those rules now also to a global and UN level.

The African Union is working on another convention on violence against women. We also have the Belém do Pará Convention. That was the first one adopted by the inter-American system, addressing specifically violence against women. But we need to progress with implementation of those norms. And now at the global level, I am also advocating adoption of an optional protocol on violence against women that could be attached to the CEDAW convention [Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women].

What we need to do is to look at social, cultural, religious and legal norms at the national level

Dubravka Šimonović

Former UN Special Rapporteur

How can we really go in the direction of having a global response to what is now a pandemic of violence against women? Now we have better data than before, although we do not still have data as we should have. It is very important that we look at solutions. So, for example, risk assessment is a tool that should be understood and promoted, used by police officers, but also by lawyers and judges, by public prosecutors, because in all those cases of intimate partners and family-related killings, we have cases in which those women in different parts of the world called police, they requested a protection order, they even got a protection order, and still they were killed because there was insufficient coordination between those agencies.

Metra Mehran, human rights activist from Afghanistan: It's not easy to speak about it, but half of the population in Afghanistan are basically dehumanised only because of their sex, only because they are women. They cannot go to school. They cannot go to work. There is no freedom of speech, freedom of movement. They cannot participate in cultural activities like sports or music. They do not have access to justice. [In September], the Taliban published laws that expand, formalise and criminalise everything about womanhood. So, as a woman in Afghanistan, the very act of speaking, your voice and your face, is being criminalised – you are subject to punishment.

When we speak about the situation in Afghanistan, it's not just any action by a single person or a group. It's ideologically and pragmatically necessary and essential for the sustainability of regime of the Taliban, because they need that space that hates women – that there is misogyny, that women are oppressed – so that the Taliban ideology can grow. That's why women inside Afghanistan who are protesting against these draconian laws call the situation gender apartheid, because we believe gender apartheid as a framework is the only existing framework that can encompass the totality of the crime that's happening in Afghanistan. That's why women advocates from Afghanistan, both inside and outside the country, and people like me who are in exile, we are trying to leverage the existing international mechanisms.

But, for example for the ICC [International Criminal Court] case, there are not enough resources to do an investigation and documentation for the case of Afghanistan, and it's hard for us to get countries to financially fund this. I know that international law is going to take a long time, but we have a golden opportunity that the crimes against humanity treaty [the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Crimes Against Humanity] is already under consideration within the UN.

But, in the meantime, I think socialising the term [gender apartheid] – creating enough solidarity around it – it can create that moral obligation for us as a global community to respond to what's happening in Afghanistan. We should work to end gender apartheid in Afghanistan, but we also should make sure that it does not become something normal for anyone in any other part of the world.

This is an abridged version of the IBAHRI showcase session, ‘Femicide, murder and other crimes against women – a social crisis’, at the IBA Annual Conference in Mexico City. The filmed session can be viewed in full here.