Preventive legal measures under Korean law against unjust bond calls

A construction site in Seoul, South Korea, November 2019. Credit: Obs70/Shutterstock

Sung Hyun Hwang

GS Engineering & Construction Corporation, Seoul

|

This article analyses the preventive legal measures under Korean law against an unjust bond call by the beneficiary/employer (the ‘Beneficiary’) upon the various unconditional bank guarantees that have been issued by financial institutions located in Korea (the ‘Issuing Bank’).

|

Introduction

Unconditional bank guarantees are typically requested to be submitted by the applicant/contractor (the ‘Applicant’) for various purposes in accordance with the underlying contract, in this context a construction contract with regard to an international construction project.

Since Korean courts have jurisdiction over preventive legal measures against unjust bond calls insofar as such a bond has been issued by a financial institution in Korea, it is worth being aware of the preventive legal measures that the Korean courts can advance. This article also looks at how unjust bond calls are different in the other developed jurisdictions based on English law.

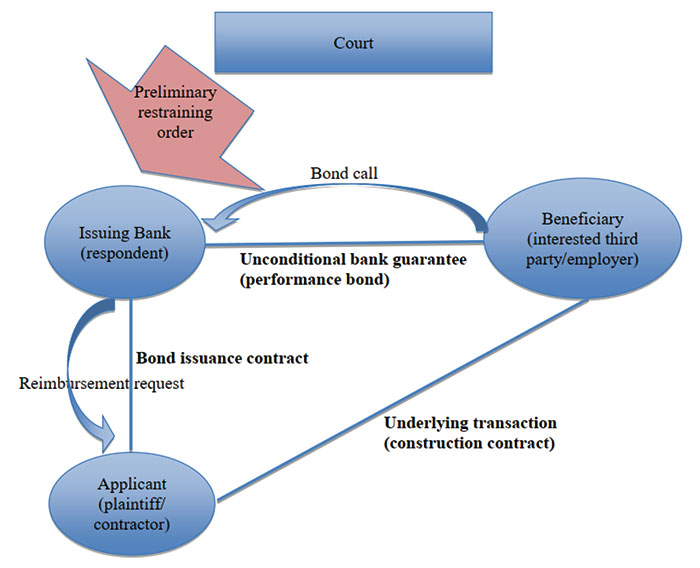

Similar to the other civil law jurisdictions, there are two preventive legal measures mainly issued by a Korean court to prevent the payment by the Issuing Bank upon the Beneficiary’s unjust bond call: a preliminary restraining order (???????); and a provisional attachment (?????). These measures are provided for under Article 300 and Article 276, respectively, of the Civil Execution Act of Korea1 (the ‘Execution Act’). This article considers the two measures in respect of the prospects of success and expected cash out, which the Applicant and the Beneficiary should assess before initiating or objecting to any preventive legal action before the Korean courts.

Preliminary restraining order

General

A preliminary restraining order, as well as the provisional attachment, is made during proceedings known as provisional, interim, preliminary or interlocutory proceedings. Such injunctions are provisional in the sense that they can be revoked during the main proceedings. However, in the event of an unjust bond call, the parties tend to have the dispute in provisional proceedings, rather than the main proceedings. The purpose of this is to prevent the Issuing Bank’s payment to the Beneficiary. Otherwise, the Issuing Bank will make a payment immediately to the Beneficiary and request the Applicant to reimburse the amount that has been paid to the Beneficiary. The main proceedings may take more than a year to reach a final decision.

Since the respondent of the preliminary restraining order is the Issuing Bank domiciled in Korea, Korean courts have international jurisdiction over such preliminary restraining orders pursuant to the relevant procedural law provisions (Article 2 of the International Private Act of Korea;2 Articles 303 and 23(1) of the Execution Act; and Article 2 of the Civil Procedure Act of Korea3).

Requirement: express abuse of rights

The preliminary restraining order requires the Applicant to satisfy two elements: (1) the Beneficiary’s express abuse of rights; and (2) the necessity of the preliminary restraining order (Article 300 of the Execution Act). In order to meet the second element, the Applicant should demonstrate that it will suffer an imminent or irreparable injury unless the court grants the order. However, it is already well recognised that the unjust bond call will lead to an immediate reimbursement request by the Issuing Bank and that the Applicant is de facto unable to refuse such a request from a financial institution due to various reasons. These reasons may include cross-default provisions in finance documents or set-off by the Issuing Bank with the Applicant’s other funds in the account opened at the Issuing Bank.

Furthermore, it would be difficult to recoup the reimbursement amount from a foreign Beneficiary, whose assets are all outside Korea, through the main proceedings.4 Therefore, the main argument point in the proceedings for the preliminary restraining order becomes the first element, the express abuse of rights, rather than the second element.

In the Korean Supreme Court (KSC) decision 2013DA53700 dated 26 August 2014, the KSC detailed and supplemented the requirements for the preliminary restraining order against the unjust bond call which had been established by the KSC under its earlier decision (KSC decision 93DA43873 dated 9 December 1994) as follows:

‘In a case where it is objectively evident that beneficiary’s demand is made by abusing the abstract and independent features of this particular type of bank guarantee, when in fact the beneficiary does not have any rights vis-à-vis the applicant, such demand constitutes an abuse of rights, and thus, impermissible. In such cases, the guarantor may withhold the payment demanded by the beneficiary. However, in consideration of the intrinsic features of first demand bank guarantee (ie, its abstract and independent features that are separated from the underlying transaction) an abuse of rights should not be easily acknowledged unless it can be recognised as it is objectively evident that the beneficiary lacks any rights whatsoever against the applicant at the time of demand for payment, without any doubt, without any needs to look into the dispute under the underlying transaction in detail, but only with the immediately available materials’ [emphasis author’s own].5

The KSC explicitly detailed the stringent legal requirements for the preliminary restraining order against an unjust bond call. It follows that it would be very difficult on any count to obtain the preliminary restraining order from the court insofar as the Beneficiary avers that its claims against the Applicant are ostensibly rightful and justifiable with the supporting materials being well prepared.

Prospects of success

Notwithstanding the aforementioned stringent legal requirements, it is often said that the high prospects of success in obtaining the preliminary restraining order6 still exist. Most preliminary restraining orders successfully granted so far have been made before the Beneficiary recognising and joining the proceedings as an interested third party and raising an objection.7 This is because the Applicants have utilised the swiftness and the structure of the preliminary restraining order. The main parties to the preliminary restraining order against the unjust bond call to whom notice is given by the court for a hearing are the Applicant and the Issuing Bank, not the Beneficiary. However, as the Beneficiary may join the proceedings (Article 23(1) of the Execution Act; and Articles 71 and 76 of the Civil Procedure Act of Korea8) and raise an objection against the preliminary restraining order (Articles 283 and 301 of the Execution Act) whenever thereafter, the order will be revoked in the end, unless the Applicant is successful in satisfying the requirement of the express abuse of rights, clearly prevailing over the Beneficiary’s counter arguments.

As such, unless the Beneficiary merely asserts its claims without any sophisticated grounds, it is very unlikely the application for the preliminary restraining order against the unjust bond call will pass the KSC’s high legal threshold: the express abuse of rights.

Figure 1: structure of preliminary restraining order

Comparison to English law

As regards the preliminary restraining order, English courts base the threshold on the fraud rule instead of the abuse of rights. The English courts require that the fraud must be ‘very clearly established’ or ‘clear and obvious’, and it must be immediately available without the need for lengthy and in-depth investigation into the underlying transactions.9

However, as to the question of whether the fraud rule under English law is stricter than the abuse of rights under Korean law, it appears that the former requires a higher standard. English courts have referenced in many previous cases10 the terms ‘dishonesty’, ‘mala fide’ intentions and so on. This suggests a subjective test, which decides whether the Beneficiary has subjective intent when it makes a bond call, and is not required for the abuse of rights under Korean law.11

Provisional attachment

General

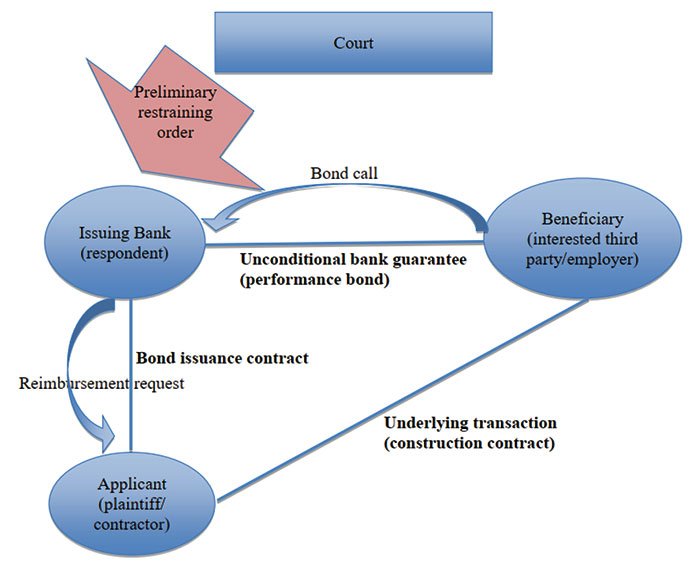

The provisional attachment, as regulated in the Execution Act, is aimed at the preservation of assets belonging to the debtor/respondent (in the present context, the Beneficiary) in order to avoid the risk that the debtor/respondent has disposed of its assets by the time that the creditor/plaintiff (in the present context, the Applicant) obtains a final judgment, which is often rendered only after protracted proceedings.

The debtor/respondent’s assets subject to the provisional attachment encompass real property, chattels, accounts and rights to payment from the third party (in the present context, the Issuing Bank). In general, the provisional attachment order is readily and quickly granted in ex parte proceedings (Article 280(1) of the Execution Act), sometimes within only a few days of the application, compared to the preliminary restraining order which requires an inter parte hearing (Article 304 of the Execution Act).

If the Applicant has plausible monetary claims against the Beneficiary such as outstanding progress payments, and the amount of these claims are equal to or more than the called amount, the Applicant may apply for the provisional attachment on the Beneficiary’s right to payment from the Issuing Bank of the called amount by satisfying the requirements under the Execution Act.

The Beneficiary’s right to payment from the Issuing Bank, which is the asset subject to the provisional attachment, is deemed to be located at the Issuing Bank’s domicile in Korea. Thus, even if the Beneficiary is domiciled outside Korea, the Korean court has international jurisdiction over such provisional attachment order pursuant to the relevant procedural law provisions (Article 2 of the Act on Private International Law of Korea;12 and Articles 278 and 21 of the Execution Act).

Requirements and prospect of success

The provisional attachment requires the creditor/plaintiff (the Applicant) to satisfy two elements: (1) a prima facie monetary claim against the debtor/respondent (the Beneficiary); and (2) the necessity of the provisional attachment that an execution of the judgment on merits would be impossible or difficult without the provisional attachment (Articles 276 and 277 of the Execution Act).

In the context of an unjust bond call, the Applicant shall demonstrate before the court that: (1) it has plausible monetary claims against the Beneficiary arising out of the underlying transaction (ie, construction contract secured by the unconditional bank guarantee) or any other transaction not secured by the concerned guarantee; and (2) unless the court grants the provisional attachment it would be difficult or impossible to recoup the monetary claims from the foreign Beneficiary whose assets are all outside Korea except its right to payment from the Issuing Bank arising out of the bank guarantee. These arguments have been typically made by the Applicant and recognised by Korean courts in multiple precedent cases. Compared to the preliminary restraining order, the provisional attachment order has been far easier to obtain in ex parte proceedings within a shorter period.

Figure 2: structure of provisional attachment

Legal uncertainty over provisional attachment

Over the past decade, many criticisms have been raised in Korea about the appropriateness of the provisional attachment as a preventive legal measure against the unjust bond call. Many consider that the provisional attachment undermines the credibility of the unconditional bank guarantees issued by Korean financial institutions by subverting the intrinsic nature of the unconditional bank guarantee13 because it has been often utilised by the Applicant as a measure to bypass the high legal threshold required for the preliminary restraining order: the express abuse of rights.

In light of this, it should be considered that as time goes by Korean courts might become more reluctant to grant a provisional attachment order against the unjust bond call. In 2014, one of the lower courts in Korea ordered the Applicant to change its application for the provisional attachment against the unjust bond call to the application for the preliminary restraining order, though it was an oral order.14 In another case in which the Applicant had applied for a provisional attachment and succeeded in obtaining the provisional attachment order, the Beneficiary thereafter joined the procedure and raised an objection, disputing heavily the appropriateness of the provisional attachment as a preventive legal measure against the unjust bond call. However, as the parties to the dispute settled prior to the final ruling of the KSC, this issue still remains a grey area.15

Comparison with other developed jurisdictions

The English technique of a freezing (Mareva) injunction serves the same purpose as the Korean provisional attachment, namely the preservation of the debtor’s assets pending litigation. There is a technical difference in that the freezing injunction is an action in personam whereas the European continental conservatory attachment, including the Korean provisional attachment, is an action in rem. Moreover, English courts will not grant the freezing injunction in order to prevent payment under the unconditional bank guarantee in a ‘before payment situation’ since they treat the unconditional bank guarantee as cash but will only grant the freezing injunction enjoining the Beneficiary from removing the proceeds of the bond call in an ‘after payment situation’ (Intraco v Notis Shipping Corp, [1981] 2Lloyd’s Rep 256, 258).16 Thus, it is not appropriate to compare in parallel the provisional attachment with the freezing injunction under English law as a preventive legal measure against an unjust bond call.

In the case of a conservatory attachment in European continental jurisdictions, which is almost the same as the provisional attachment in Korea, it appears that whether or not the conservatory attachment can be granted in order to prevent payment under the unconditional bank guarantee still remains a grey area, similar to Korea. There have been instances where some courts granted a conservatory attachment in order to secure payment, which the employer/Beneficiary owed to the contractor/Applicant, after having identified that the Applicant’s promise to renounce defences against the Beneficiary’s right to payment under the unconditional bank guarantee did not imply that the Applicant was prohibited from attaching the guarantee funds.17 On the other hand, some courts refused to grant the same after having observed that the attachment frustrates the envisaged purpose and effect of the unconditional bank guarantee. Thus, they came to the conclusions that the conservatory attachment is incompatible with the agreement between the Applicant and the Beneficiary and that the guarantee shall remain in full force and effect (Rb Breda, 22 July 1992, KG 1992, 301).18

Other factors to consider

Security ordered by the court

In practice, when the court grants the preliminary restraining order or provisional attachment against the unjust bond call, it almost always orders the Applicant to furnish security for potential damages to the Beneficiary which might be caused by the wrongful preliminary restraining order or provisional attachment (Articles 280 and 301 of the Execution Act). The amount and composition of such security is determined at the discretion of the court. However, when the attached property is a monetary claim (ie, the Beneficiary’s receivables from the Issuing Bank under the unconditional bank guarantee), it is generally known that the court orders the Applicant to furnish about 40 per cent of the attached monetary claim as security with the condition that a certain percentage19 of that amount is cash.20

Issuing Bank’s position

In the event of an English court having non-exclusive or exclusive jurisdiction over the unconditional bank guarantee, it may order the Issuing Bank to make a payment to the Beneficiary despite a preliminary injunction, provisional attachment, restraint order or any other decision of a similar nature previously made by a foreign court.21 Further, non-payment of the Issuing Bank upon the Beneficiary’s bond call may undermine the commercial reputation of the unconditional bank guarantee issued by Korean financial institutions, whether or not it is due to the order of Korean court.

Traditionally, Korean Issuing Banks had a tendency to avoid being involved in the disputes between the Applicant and the Beneficiary; and, accordingly, it was normal that they had no position in the proceedings in which the Issuing Bank was the respondent (ie, the preliminary restraining order).22 This was one of the reasons why the preliminary restraining order was granted relatively easily in the past at the lower court before the Beneficiary recognising and joining the proceedings as an interested third party. Recently, however, some Korean Issuing Banks have expressed that they do not want any preliminary restraining orders or provisional attachment orders, after having recognised the concerns discussed in above. Further, some Korean Issuing Banks participate actively in the proceedings in order to prevent the orders being granted by a Korean court based on the limited and biased information that has been submitted by the Applicant.

Supreme Court of South Korea. Credit: Rémi Cormier [CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]

Conclusion

Given the well-established high legal threshold for a Korean court to grant the preliminary restraining order against the unjust bond call (ie, the express abuse of rights), unless the Beneficiary merely asserts its claims without any sophisticated grounds, it would be arduous to obtain the preliminary restraining order in the same way as other developed jurisdictions.

In the past, the provisional attachment order was far easier to obtain in ex parte proceedings within a shorter period compared to the preliminary restraining order. However, due to the absence of a KSC ruling on this issue and many criticisms that have been recently raised in Korea with respect to the appropriateness of the provisional attachment as a preventive legal measure against the unjust bond call, whether or not the provisional attachment can be granted in order to prevent payment under the unconditional bank guarantee remains a grey area.

Notes

1 Act No 13952/2016.

2 Act No 1375/2016.

3 Act No 14966/2017.

4 ???(Korean Supreme Court) Decision 93DA43873 decided 9 December 1994.

5 Author’s translation.

6 Seung Woo Shim, ‘Preservative Measures Concerning Letters of Credit and Independent Bank Guarantees’, Journal of Civil Judgment Enforcement Law (2015) 11, 369, pp 379–380.

7 Ibid, pp 390–391.

8 Act No 14966/2017.

9 Harbottle v Nat Westminster Bank[1977] 2 All ER 862; Edward Owen v Barclays Bank [1978] 1 All ER 976; and Boliventer Oil v Chase Manhattan Bank [1984] 1 WLR 392.

10 Roeland I V F Bertrams, Bank Guarantees in International Trade (4th edn, Kluwer Law International 2013), p 366: State Trading Corp of India v ED & F Man (Sugar) Lord Denning [1981] Com LR 235; GKN Contractors v Lloyds Bank Plc [1985] 30 BLR 48; and Deutsche Ruckversicherung AG v Walbrook Insurance [1994] 4 ALL ER 181 at 196, 197.

11 Seung Hyeon Kim, ‘A Study on How to Cope with the Abusive Call on On-demand Bonds’, The International Commerce & Law Review (2016) 69, 261, pp 273–274.

12 Act No 1375/2016.

13 Jin Su Yune, ‘Economic Rationality of the Independent Bank Guarantee and the Abuse of Right Doctrine’ Bup Jo (2014) 63–5, p 5.

14 Case No 2014KADAN201638, ????????(Seoul Southern District Court).

15 Case No 2014KADAN812746, ????????(Seoul Central District Court).

16 See n 10 above, Bertrams, para 17.9.

17 Trib gr inst Paris, 13 May 1980, D 1980 J p 488.

18 See n 16 above, paras 17.4 and 17.5.

19 It is hard to provide a definite figure, as it varies depending on various factors, including, inter alia, each court’s internal non-binding guideline, financial credibility of the Applicant, and the amount of the attached monetary claim.

20 In general, the rest of the security amount may be furnished with the other bank guarantees as per the sanction of the court.

21 Power Curber Int’l Ltd v National Bank of Kuwait [1981] 1 WLR 1233.

22 See n 6 above, pp 388–389.

|

Sung Hyun is a legal counsel in the International Legal Team at GS Engineering & Construction Corporation in South Korea and can be contacted at sh9859a@gsenc.com.

|

Back to top