China spreads its wings

Stephen Mulrenan

As some economies adopt a protectionist approach to trade, China is doing the opposite. A recent $295m acquisition in Australia of land twice the size of Belgium is the latest example of the country expanding its trade and investments worldwide, presenting itself as a responsible global leader.

Newly inaugurated United States President Donald Trump has called the North American Free Trade Agreement the ‘worst trade deal in history’ and stated that he will renegotiate or terminate it at the earliest opportunity. According to Trump, the agreement, introduced in 1994, has contributed to the decline of the US manufacturing sector and to American job losses.

The new president, elected largely on the back of an anti-globalisation platform, has also announced his intention to impose a 20 per cent tax on goods made in Mexico and sold in the US, and proposed a 45 per cent tariff on imports from China.

Trump’s stance on China during his presidential campaign was readily dismissed as election rhetoric until his appointment of two prominent China critics as key members of his trade team. Peter Navarro, author of Death by China, was named Director of the newly created National Trade Council, while Robert Lighthizer has assumed the role of US Trade Representative.

Navarro has been particularly scathing towards China’s government, describing it as ‘brutal’ and ‘authoritarian’. He has echoed Trump in accusing Beijing of unleashing ‘carnage’ on the US economy through its ‘rapacious’ trade policies and currency manipulation.

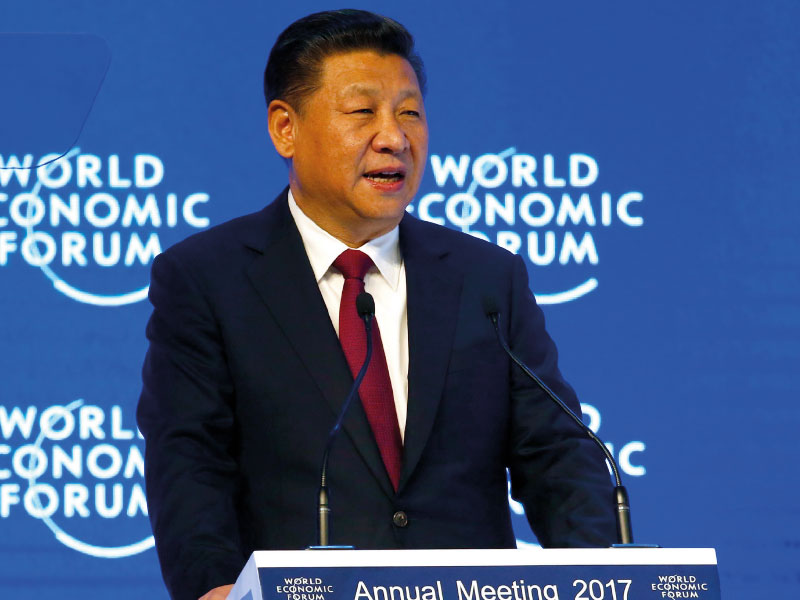

Goldman Sachs alumnus and senior adviser to President Trump, Anthony Scaramucci, recently asserted that the current trade relationship between the US and China favours China, but that the US would win any trade war with the world’s second largest economy. Chinese President Xi Jinping responded to the comments in his address at January’s World Economic Forum – the first by a Chinese leader – where he warned that no country would emerge as a winner in a trade war. ‘Pursuing protectionism is like locking oneself in a dark room,’ he told the audience. ‘While wind and rain may be kept outside, so are light and air.’

Controlling the electricity grid, for instance, doesn’t mean China can just switch off the electricity to coerce Australia into doing what Beijing wants

Graham Wladimiroff

Assistant General Counsel for APAC at Akzo Nobel Investment Co (China) and Corporate Counsel Forum Liaison Officer of the

IBA Asia Pacific Regional Forum

While some other world leaders, such as Germany’s Angela Merkel, stayed away from the Forum, China sent its largest ever delegation to Davos. In addition to Xi, the delegation included business leaders such as Jack Ma of e-commerce giant Alibaba and Wang Jianlin of multinational conglomerate Dalian Wanda. The message was clear: expect a more expansionist China.

In addition to the US adopting a more protectionist position, the United Kingdom’s Brexit referendum vote to leave the European Union in June 2016 and growing concerns over an emerging new wave of populism in Europe (elections take place this year in France, Germany and the Netherlands) have encouraged China to attempt to extend its influence across the world.

China’s launch of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and its revival of the Silk Route trade corridor from Asia to the Middle East and Europe through its One Belt, One Road initiative are part of its long-term ‘Going Out’ policy. Instigated at the turn of the century, the strategy encourages Chinese enterprises to invest overseas and to become the primary global advocate for globalisation – a process that has served it so well over the last two decades.

Australian land grab

China’s expansionist ambitions have, at times, garnered vehement opposition and sensationalist rhetoric. For example, China’s controversial territorial claims in the South China Sea have resulted in its neighbours investing heavily in military hardware – such as planes, ships and submarines – in a bid to counter what they see as Beijing’s bid to dominate the strategic waterway.

The rapid economic growth of China has also coincided with a rising domestic demand for natural resources. While the country has been making land acquisitions in regions such as Africa since the 1960s, this so-called strategy of ‘land grabbing’ has escalated since the sharp increase in international food prices in 2007 and 2008.

China’s land acquisitions for agricultural and biofuel production, for instance, are similar to those made by other countries and corporate players. However, such deals have often caused great international unease over issues such as the large-scale resettlement of populations.

China’s World Bank

The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) was launched with the intention of filling the funding gap for the development of roads, railways, energy corridors, power plants, rural infrastructure and ports in countries across the Asia-Pacific region. Many of those states that have so far received funding from the AIIB are located along China’s One Belt, One Road initiative.

Celebrating its one-year anniversary on 16 January 2017, the China-founded and led $100bn not-for-profit international investment bank has attracted 57 founding members from across Africa, Asia, the Americas, Europe, the Middle East and Oceania. It hopes to expand its membership to 90 countries by the end of this year.

Two countries that abstained from becoming AIIB members were Japan and the US. This was due to fears that the Bank would serve merely to spread Chinese influence, infringe humanitarian and environmental standards, and become a rival to the World Bank and Asian Development Bank. In stark contrast, traditionally staunch US allies such as Canada, France, Germany, South Korea and the UK, embraced the new institution and became fully-fledged members.

President Trump’s former policy adviser James Woolsey recently revealed that there was a consensus in Washington that the Obama Administration’s opposition to the AIIB was a strategic mistake. Rather than compete with existing infrastructure investment banks, the AIIB partnered with such institutions on all nine of its projects in 2016.

Last year, it was responsible for more than $1.7bn in loans for infrastructure projects, including:

-

a power distribution system in Bangladesh;

-

slum upgrades in Indonesia;

-

road improvement in Tajikistan;

-

a power plant in Myanmar;

-

advanced maritime infrastructure in Oman;

-

a key stretch of highway along the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor in Pakistan; and

-

$600m of the $11.7bn needed for the Trans-Anatolian pipeline, which stretches from Azerbaijan to Europe.

The AIIB intends to invest $2.5bn across 10 to 15 additional projects in 2017.

Source: Forbes

One recent transaction to have caused a stir was the $295m sale of Australia’s largest landowner, Kidman & Co, to a consortium that included Chinese property developer Shanghai CRED and Australia’s richest person and the world’s richest woman, mining owner Gina Rinehart.

Twice the size of Belgium, the 101,000 square kilometre Kidman property holds around 1.3 per cent of Australia’s total land area and 2.5 per cent of its agricultural land. The 185,000 cattle that roam free are a key source of beef for export to Japan, the US and Southeast Asia, and therefore a potentially lucrative source of food security.

The property deal, which is the largest in Australian history, was rejected by its Government on two previous occasions for being ‘contrary to the national interest’, according to Treasurer Scott Morrison. Following the failed acquisition by Shanghai Pengxin in an all-Chinese offer, Chinese-owned Dakang Australia Holding made a joint bid of $283m with ASX-listed Australian Rural Capital (ARC).

While Canberra cited the proximity of the Kidman property to a top-secret government weapons-testing range in central Australia as reason for rejecting the previous bids (the Anna Creek station was subsequently pulled from the deal), the failed transactions could also be explained by a growing concern in Australia about foreign purchases of local infrastructure. As a case in point, the Government last year rejected a Chinese bid for Australia’s largest electricity network.

While the Dakang-ARC bid (which was backed by Kidman) would have seen the former hold an 80 per cent stake, with the partners jointly overseeing the management of the business, the successful Australian Outback Beef consortium is, crucially, 67 per cent owned by Rinehart and 33 per cent by Shanghai CRED.

Such a structure is likely to have been deemed far more palatable to Australia’s Foreign Investment Review Board, given the Australian public’s anxiety over the country’s trade dependency with China.

While some other world leaders stayed away from the World Economic Forum in January 2017, China sent its largest ever delegation, including President Xi Jinping and prominent business leaders

However, Shanghai-based Graham Wladimiroff, Assistant General Counsel for APAC at Akzo Nobel Investment Co (China) and Corporate Counsel Forum Liaison Officer of the IBA Asia Pacific Regional Forum, does not see China exploiting its trading partners by adopting politically coercive policies.

‘I’m not so sure that controlling the electricity grid, for instance, means that China or any other state – through private owners who hold the shares – can just decide to switch off the electricity in order to coerce Australia into doing what Beijing wants. There are measures one can take in the courts of Australia to stop that and, in the worst case, Australia can nationalise,’ he says.

‘I see more of an argument for threats to foreign investment in China. Depending on how dependent a country is on trade with China, that could be a card to play.’

A member of the IBA International Sales Committee, who wishes to remain anonymous, adds that most countries use protectionism policies to try to strengthen their economies. ‘Taking the example of anti-dumping investigations/sanctions and anti-monopoly actions against Chinese companies in foreign jurisdictions, although there have been anti-dumping orders and rejection of substantial transactions with monopolistic conduct in China, they are few in comparison to those against Chinese companies in foreign countries,’ he says.

One Belt, One Road

China’s strategy of becoming the primary global advocate for globalisation has also recently seen it escalate trade and investment ties with Europe. At the start of 2017, for example, it launched a direct rail freight service bound for Barking Rail Freight Terminal in East London. The train in question takes two weeks to travel 12,000 kilometres across seven countries, and contains clothes, bags and various household items.

The freight service is just one small part of China’s ambitious One Belt, One Road project, which integrates its export-dominated production industries with consumer markets across the world. The ‘Belt’ refers to those countries on the original Silk Route – through Central and South Asia and into Europe – while the ‘Road’ refers to a network of ports linking China with South Asia, the Middle East and East Africa.

Since 2015, the Chinese Government has been keen to boost its economy in the face of slowing export and economic growth. Officially announced in September 2013, the One Belt, One Road initiative allows China to invest in, and capitalise on, the largely unexploited transit zone from Asia to Europe and create new demand for Chinese exports.

New outbound investment restrictions

In 2016, the value of China’s currency depreciated over six per cent against the US dollar and China’s foreign exchange reserves dropped sharply. This has caused Beijing concern and, while no new laws or regulations have been officially promulgated, public statements by Chinese government officials suggest that new measures to tighten outbound direct investment (ODI) approval have been implemented in practice.

Chinese regulators recently reiterated the government’s continued support for the Going Out policy and the One Belt, One Road initiative, but emphasised the importance of monitoring irrational ODI by Chinese companies.

It is rumoured that, until September 2017, the Chinese government is effectively implementing stricter scrutiny over six types of ODI:

-

Extra-large outbound investments, including:

-

outbound real property acquisitions or developments by state-owned enterprises with an investment value of $1bn or above;

-

outbound investments of more than $1bn outside of the core business of a Chinese buyer; and

-

extra-large outbound investments valued at $10bn or more.

-

ODI by limited partnership;

-

Minority investments in listed companies: ODI involving the acquisition of ten per cent or less of the shares in an overseas listed company;

-

‘Small parent, big subsidiary’: ODI where the size of the target is substantially larger than the size of the Chinese buyer, or where the Chinese buyer makes the investment shortly after its establishment;

-

Privatisation: participation in the delisting of overseas listed companies that are ultimately controlled by Chinese companies or individuals; and

-

High risk/low return transactions: ODI into an overseas target resulting in a high-debt to asset ratio and a low return on equity.

Source: Allen & Overy

According to HSBC Global Research, China’s overseas (non-financial) investment grew by an astonishing 53.7 per cent year-on-year in the first nine months of 2016, to reach $134.2bn. Surprisingly, investment in countries on the One Belt, One Road initiative decreased by 7.6 per cent year-on-year to $11.1bn (accounting for only 8.3 per cent of total China non-financial overseas investment).

One explanation for this is the rise in global uncertainty following the UK’s Brexit vote and the Trump victory in the US, which is encouraging new investment to flow into developed rather than emerging markets.

Investment controls

Under the One Belt, One Road initiative, China is financing huge improvements in infrastructure such as IT, ports, rail, roads and telecoms. But there are concerns over whether the money will be deployed wisely, or is simply wasted on projects that should not have been funded in the first place.

Last year, China introduced new measures to tighten outbound direct investment approval. And while this may have more to do with China’s currency depreciation and preventing hot money capital flight, China has been able to say to the world that the monitoring and stopping of irrational payments is consistent with the actions of a responsible global leader.

Wladimiroff says: ‘These controls are about protecting China from a financial drain, and not, as far as I can see, to improve the choice of assets to buy. To the extent the authorities in China want to influence the choice and quality, ie strategic assets, they were already doing that.’

The International Sales Committee member says there are bound to be other challenges in cross-border projects involving a number of countries with historical influence in the regions along the One Belt, One Road route. ‘They include different cultures, different levels of technology, different laws and how they may deviate in practice, willingness in commitment, and security participation with development banks and past repayment obligations.’

Pursuing protectionism is like locking oneself in a dark room. While wind and rain may be kept outside, so are light and air

Xi Jinping

Chinese President

However, despite the recent moderation in One Belt, One Road investment, the outlook in 2017 and beyond looks healthy. China will welcome world leaders to Beijing in May for its One Belt, One Road Summit, while the China Development Bank lists more than 900 projects linked to the initiative, with an aggregate investment value of $800bn.

‘Keynes would be proud,’ says Wladimiroff. ‘Belt and Road is mainly about keeping the factories and workers of China going. There may be a mild argument for geo-political influence, but China is still not too good at this. At times, it seems as if they think they can buy loyalty by just throwing money at others. However, with proceeds reverting to China and jobs generated meaning Chinese jobs, I would say the main interest is harmony and tax income at home.’

It is perhaps fitting that in the week in which the US inaugurated its 45th President, the theme for the World Economic Forum’s 2017 Annual Meeting was ‘Responsive and Responsible Leadership’. According to the Forum: ‘The emergence of a multipolar world cannot become an excuse for indecision and inaction, which is why it is imperative that leaders respond collectively with credible actions to improve the state of the world.’

As Trump formally withdrew the US from the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade deal – one of his first actions upon becoming President – China once again reiterated its commitment to free trade by publicly backing alternatives such as the Free Trade Area of the Asia Pacific and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. China is likely to further look to seize the opportunity to become the world’s leading advocate of the benefits of globalisation.

Stephen Mulrenan is a freelance journalist based in Hong Kong. He can contacted on stephen@prospect-media.net